Shows

When the City Looked Back: Park Hyunki’s Radical 1981 Performance

Park Hyunki

Pass Through the City

Gallery Hyundai

New York

Nov 6, 2025–Feb 14, 2026

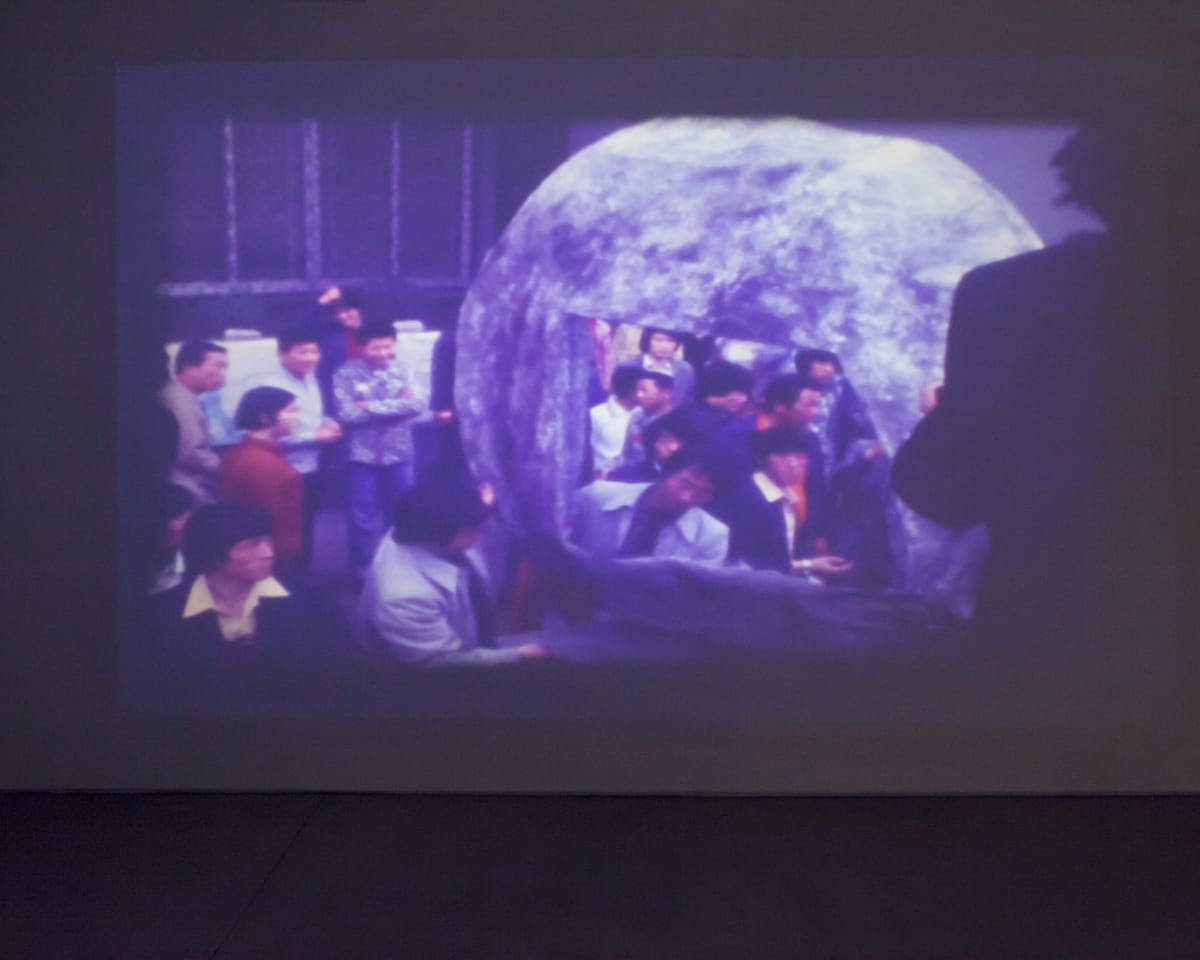

A heavy-duty flatbed truck moves through an urban landscape, carrying an artificial boulder nearly as tall as the people who gathered to watch. Its deliberate pace appears contagious: surrounding vehicles decelerate, while curious faces peek out of passing bus and taxi windows. The scene comes from Park Hyunki’s Pass Through the City (1981), a three-part performance in which the artist sent a mirror-embedded boulder through the streets of Daegu, South Korea, turning the city into a stage for reflection. Revisited at Gallery Hyundai through photographs and videos, the project captures Park’s early inquiries into how technology conditions seeing and being seen at the dawn of Korea’s media age in the 1980s.

Stills from PARK HYUNKI, Pass Through the City - 8mm film, 1981, single-channel video, color, no sound: 34 min 44 sec. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai.

Upon graduating from college in 1967, Park relocated from Seoul back to Daegu in the country’s southeast. He would later recall that “in the early ’70s, no one could name the reason behind their decision to leave Seoul to return to their hometown.” For many young artists, the decade proved difficult: under the Yushin government (1972–1979), President Park Chung-hee’s regime imposed martial law, tightening control over individual life to prioritize economic growth. While avant-garde collectives such as AG (Avant-Garde) and ST (Space and Time) pioneered experimental art forms in the late ’60s, most had lost momentum as censorship and surveillance intensified. Within this climate, Park’s gesture—transporting a massive boulder inlaid with a mirror through the city—was ambitious and radical, a performance that tested the boundaries between art and public life.

At Gallery Hyundai, photographs lining the walls near the entrance show the boulder placed on a street facing Daegu Bank. Nearby, a digital screen plays an hour-long video of closed-circuit television footage that recorded passersby reacting to the work, while an analog monitor displays the various devices that tracked the rock’s movement across the city—from medium-format cameras to CCTV. During the 1981 performance, Park even broadcasted the live surveillance feed at Maekhyang Gallery—only months after color television entered the Korean market in December 1980.

Installation views of PARK HYUNKI’s Pass Through the City - 8mm film, 1981, single-channel video, color, no sound: 34 min 44 sec, at Gallery Hyundai, New York, 2025. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai.

Despite the project’s pioneering use of emerging technology, the “moving image” at its core was not electronic but reflective: a mirror set within the boulder. The reflections it produced shifted for each passerby, whose movements animated its surface. Video documentation reveals ambivalence among onlookers—some walk past without pausing, while others stop, circle, or reach out to touch the stone. Although a few confront their own reflection, many linger on the boulder itself, probing its texture and form.

The two decades leading up to Park’s performance created a fraught environment for many avant-garde artists, yet also produced the very systems of infrastructure and technology that experimental work would come to depend on. Park’s documentation makes this paradox visible: the camera hovers over a wide asphalt road bordered by utility poles, electric wires, and rows of commercial facades—movie theaters, nightclubs, banks. These scenes reveal both the physical conditions that enabled Pass Through the City and the mechanisms of modernization that circumscribed personal freedom. The city’s empty roads—occupied mostly by cabs and buses, with a noticeable lack of private vehicles—hint at the scale of the project, while the built environment underscores the artist’s awareness of the structures that link technological progress with control.

Stills from PARK HYUNKI, Pass Through the City - 8mm film, 1981, single-channel video, color, no sound: 34 min 44 sec. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Hyundai.

45 years ago, amid pervasive surveillance and state-monitored media, what did it mean to appear onscreen? In Pass Through the City, one senses a quiet wonder in the reflections of onlookers as they glimpse their own image in public space.

Park rendered tangible the gap between lived experience and its mediated representation. The mirrored boulder captured both a rapidly changing nation—its economic growth inextricable from the violent imposition of modernization—and the subtle hesitation and curiosity of those encountering their likeness within it. Today, a handheld screen can reproduce one’s image anywhere, instantly; yet the conditions under which such images are circulated, contextualized, and even claimed remain unresolved. In this light, Park’s performance feels uncannily prescient—a meditation on visibility and power that anticipated a world where seeing and being seen are inseparable.

Min Park is a writer from Seoul, currently based in New York.