Shows

The Prismatic Continuum of “The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989”

*updated January 6, 2023

Oct 21, 2023–Feb 11

“The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989”

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Philadelphia

In “The Shape of Time: Korean Art after 1989” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, curators Elisabeth Agro and Hyunsoo Woo with Taeyi Kim presented 28 South Korean artists working since 1989, a span of three decades they deem “the long twenty-first century.” These artists, born between the 1960s and 1980s, are the last generation to witness the military regime of South Korea and emphasize the handmade in their craft-driven approaches. They mark time through labor and practice; others use time materially, documenting or marking it through photography and video. Throughout these diverse practices, time is a prism through which the artists contend with the now 70-year division between North and South Korean people, as reflected by the catalog’s five themes: “transition,” “tension," “displacement,” “conformity,” and “feminist resurgence.” (In the exhibition, these themes are translated into the confluent "keywords" of Dissonance," "Reinvention," "Coexistence," "Being Seen," and "Portraying Anxiety.")

The theme of “tension” was articulated literally and figuratively through SK 01-06 (2018–19) and BR 04-04 (2015–16) from Kyungah Ham’s What you see is the unseen / Chandeliers for Five Cities series. Both stemming from Ham’s decade-long “Embroidery Project,” the works depict hazy mirages of crystal chandeliers hand-embroidered onto dark cloth. The artist sends computer-rendered designs to North Korea through Chinese or Russian intermediaries to be embroidered by anonymous female workers, as contact between the two Koreas is forbidden. According to the curators, the chandelier symbolizes for Ham how Korea has been shapeshifted by foreign interference over time, such as through Japanese colonial rule and US-backed leadership.

Attentive to the political and economic realities of the South, Noh Suntag presents Forgetting Machines (2005– ), a series of portraits for which he re-photographed a funerary picture from the tomb of someone who died in the pro-democracy Gwangju Uprising (May 18–27, 1980). Each photograph displays the original portrait’s decay and degradation, evidencing how memories are warped over time. Following these affectionate images, perhaps the most personal and poignant work on view was Minouk Lim’s Portable Keeper series (2009–22), in which the artist adorns wooden walking staffs with various found, almost Duchampian readymade materials, such as colorful red string or ecru-colored spheres. The staffs were given to Lim by the late artist Chai Eui Jin (1937–2016), who carved them from branches he foraged while walking around the village sites of the 1949 Mungyeong massacre. Having borne witness to this violence, for Chai each carving served as an effigy to someone murdered. In gifting the staffs to Lim, he ensured that their memories continued, while Lim’s augmentation inscribes them with contemporaneity. Suspended in the gallery, these objects were caught between past and present, echoing their stance between traditional Korean craft-making and Euro-American modernism.

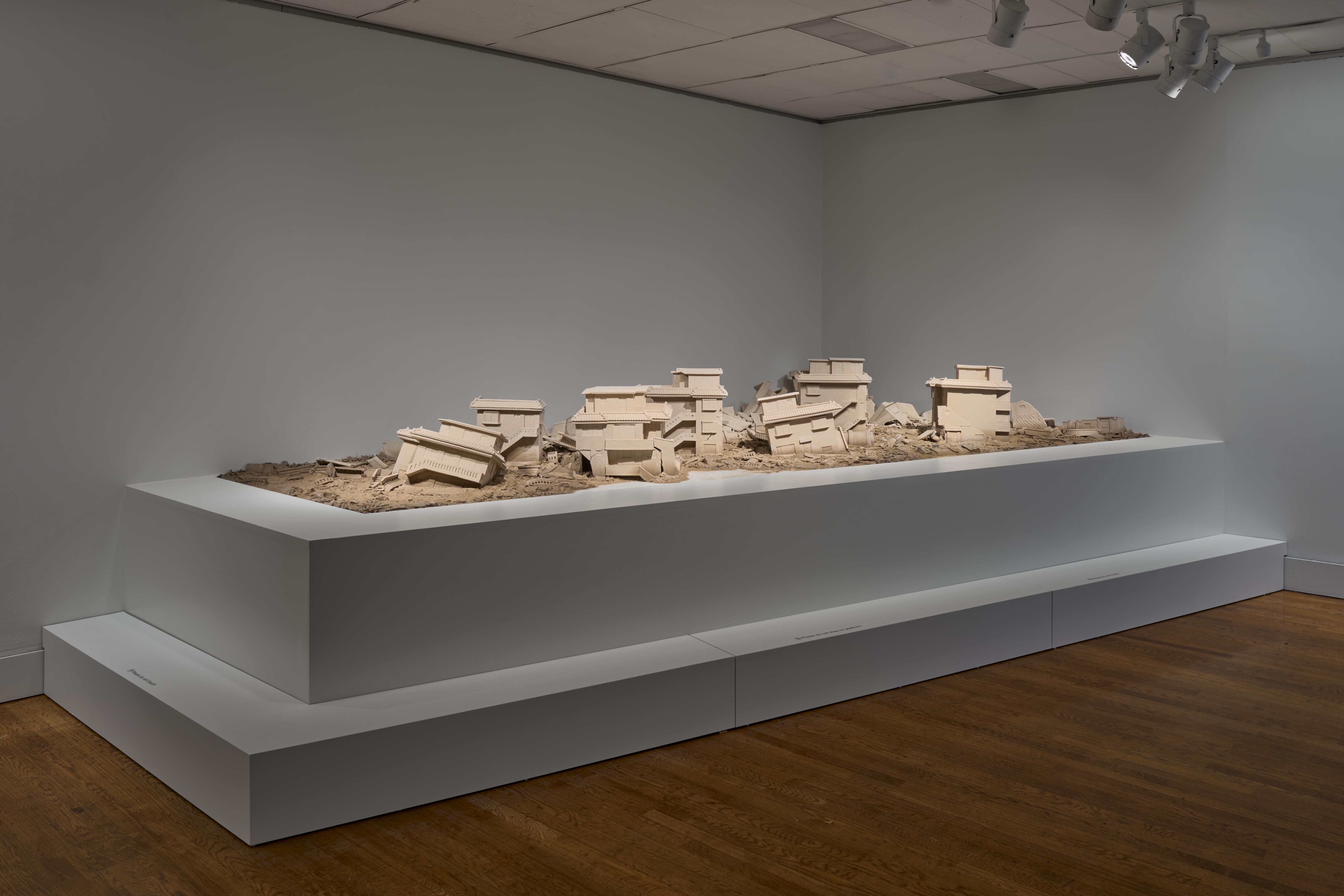

If memory is fungible and constantly shaped by the present, so too is the urban landscape, as evoked in the “displacement” section by Kim Juree’s Evanescent Landscape—Hwigyeong: Philadelphia (2023) a topography of partial ruins, rendered in soil, of the Hwigyeong-dong neighborhood of Seoul that was redeveloped in early 2000s. Both Forgetting Machines and Evanescent Landscape allude to the lived experience of globalization and modernization in the 20th and 21st centuries, demonstrating how people and ideology can morph a landscape. Such “displacement” was also apparent in Yeondoo Jung’s Eulji Theater (2019), a sound, photograph, and LED-light installation that engages with the landscape and its associated imagination. At the work’s center is a history-painting-sized photograph of Eujli Observatory depicting actual tourists alongside performers paid by Jung, gazing out towards the seemingly uninhabited rolling hills of the Taebaek Mountains. Adjacent to the photograph were audio headsets relaying a story told by a fictional guide. Listening and looking northward, curiosity becomes fantasy, as one’s imagination envisions collective life on the other side of the demilitarized zone established in 1953. “Division” thus emerged ostensibly throughout the exhibition as a reminder of the partition’s political reality.

,%202011,%20OH%20Jaewoo%20(b.%201983),%20Single-channel%20video%20,%2010%20minutes,%20collection%20of%20the%20artist.%20View%20Two.jpg)

The curatorial choice of eschewing a medium-specific or chronological organization enabled thoughtful consideration of social and political issues. For instance, “conformity” between past, present, and future was eloquently expressed in Oh Jaewoo’s Let’s Do National Gymnastics! (2011), a black-and-white single-channel video in which a man and a woman reenact the obligatory morning exercises they performed as school children. This routine was required after the pledge of allegiance in all Korean schools from 1977 to 1999 and accompanied by the Korean National Stretch Anthem. Although no longer mandatory, these exercises are encoded—remembered—in the bodies of most South Korean adults today. The video was installed on a small monitor, but the sound of the Anthem reverberated through several of the galleries, its echo an audible reminder of how indoctrination operates through iteration, like for Koreans throughout the 20th century. Following “conformity” was theme of “feminist resurgence,” wherein Yuni Kim Lang’s Comfort Hair (2013) and the accompanying photograph, Comfort Hair—Woven Identity I (2013) critique how women’s bodies have been historically contorted by society. The works were squeezed tightly into a gallery corner beside Chang Jia’s photograph series Standing Up Peeing (2006), each of which depicts a nude woman standing erect, mid-urination—a subversion of the typically male-associated act that recalls Sophy Rickett’s seminal Pissing Women series (1995).

Throughout the exhibition, works were materially, formally, and conceptually loaded. Situating them so snuggly together in the gallery space diluted their impact. Still, the thematic and full approach of “The Shape of Time” effectively suggested that the sense of history is a prismatic continuum, reflecting and reifying a divided Korean culture, where temporality is contoured by custom and culture.

Leah Triplett Harrington is a writer and curator currently serving as Director of Exhibitions & Contemporary Curatorial Initiatives at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, PA.