People

The Mosaic Body: Interview with Oyjon Khayrullaeva

For the inaugural Bukhara Biennial, Uzbek artist Oyjon Khayrullaeva created Eight Lives (2024–25), a series of monumental mosaic sculptures depicting vital human organs installed across historic sites in her hometown. Drawing on the floral ornaments of Islamic architecture in Samarkand and Bukhara, the artist transformed architectural details into anatomical forms. In this conversation with Singaporean writer Chin-chin Yap, Khayrullaeva discusses her transition from photography to digital collage, the psychosomatic effects of creating each installation for the biennial, and how her practice transmutes bodily pain into blooming, regenerative beauty.

What’s the meaning of @janajaaan, your Instagram name?

This is the most unexpected question! It goes back to my school years. My full name is Oyjon, which means “moon soul”—“Oy” refers to the Moon, and “jon” translates to “soul” or “dear.” My teacher took the last syllable and started calling me affectionately “Jona,” and soon my friends and classmates picked it up too. One of my friends used to tease me and sing “Jana jan,” so when Instagram first appeared I chose that as my username. It has been 13 years since then, and I’ve never changed it.

How did you become an artist, and how many years have you been practicing?

I actually became an artist quite recently, about three or four years ago. Before that, I was a photographer. After a period of depression, I started asking myself what I wanted to do with my life. I had always wanted to be involved in art, but I ended up choosing a completely different path. I studied restaurant and tourism management in Europe, and later political science. That’s exactly what pushed me into depression, because my soul wanted something else entirely.

My healing began about four years ago, when I started traveling around Uzbekistan and got curious about my roots, which I had never cared about before. I saw the incredible beauty of my country and its people. Every region has different landscapes, dialects, clothes, food, and faces—that diversity felt magical.

During those trips, I became fascinated by the architectural ornamentation of Samarkand and Bukhara. Islamic mosaic completely swept me off my feet, and I thought, “why not turn this into something new?” I don’t know how to draw at all, and honestly I’m not that interested in it either, so I looked for another way to express myself, and found digital collage. I started photographing mosaics and building collages out of those images. That’s where the idea for my work came from. My imagination is pretty wild: it draws on my family’s stories, women’s mythology, vivid dreams, psychological states, and so on.

Eight Lives is an important installation in your oeuvre. In some ways, it seems quite different compared to your earlier works, at least from what I have seen on Instagram. Could you please share what inspired you to create this series, specifically for the inaugural Bukhara Biennial? What do the “eight lives” refer to, and how did you select the locations for each mosaic sculpture?

Yes, this series is very different from my other works, but I actually started it back in 2023, long before the biennial. I had no idea it would even become a full project at first, but after two years of development, it all came together and concluded in January for the biennial.

The inspiration came from several sources: the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis in Samarkand; the connection between mental and physical health; and the Sufi concept of paradise gardens—that paradise should exist within you.

While walking through the necropolis, I noticed multiple mausoleums completely covered in floral mosaic ornamentation. As I was studying them up close, a thought hit me: “these flowers look so much like veins and vessels in the human body.” I took a lot of photos, shot every detail, and realized I wanted to use those images to construct a human organ. As this idea developed, I kept returning to the imagery of the internal paradise. In Islamic mosaics, floral motifs represent paradise gardens, which explains the strong resonance with this concept. I love Sufi culture because it sees paradise not as a distant promise, but as a quiet inner garden—a state of a cleansed heart where pain transforms into light, and the soul finally finds peace.

The initial inspiration, in fact, emerged from pain. As I mentioned earlier, I struggled with depression for three years, and I still have severe anxiety and arrhythmia, to put it precisely, which all have taken a toll on my body. During one of the attacks, I began to realize how complex yet intricately organized our body is. The experience prompted me to read about the anatomy of the human heart and make a collage with photos I took in Samarkand. That’s how the collage-organ was born.

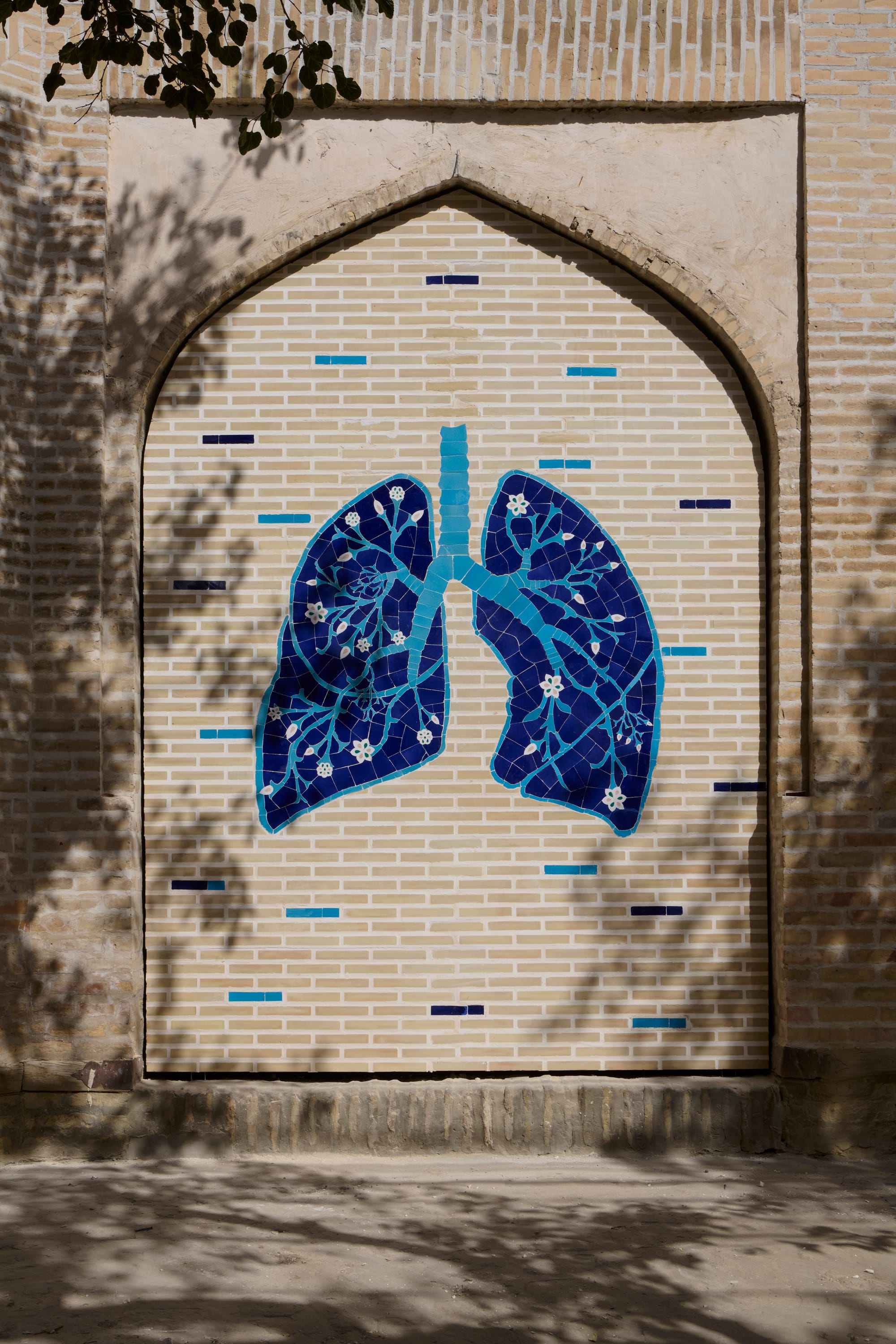

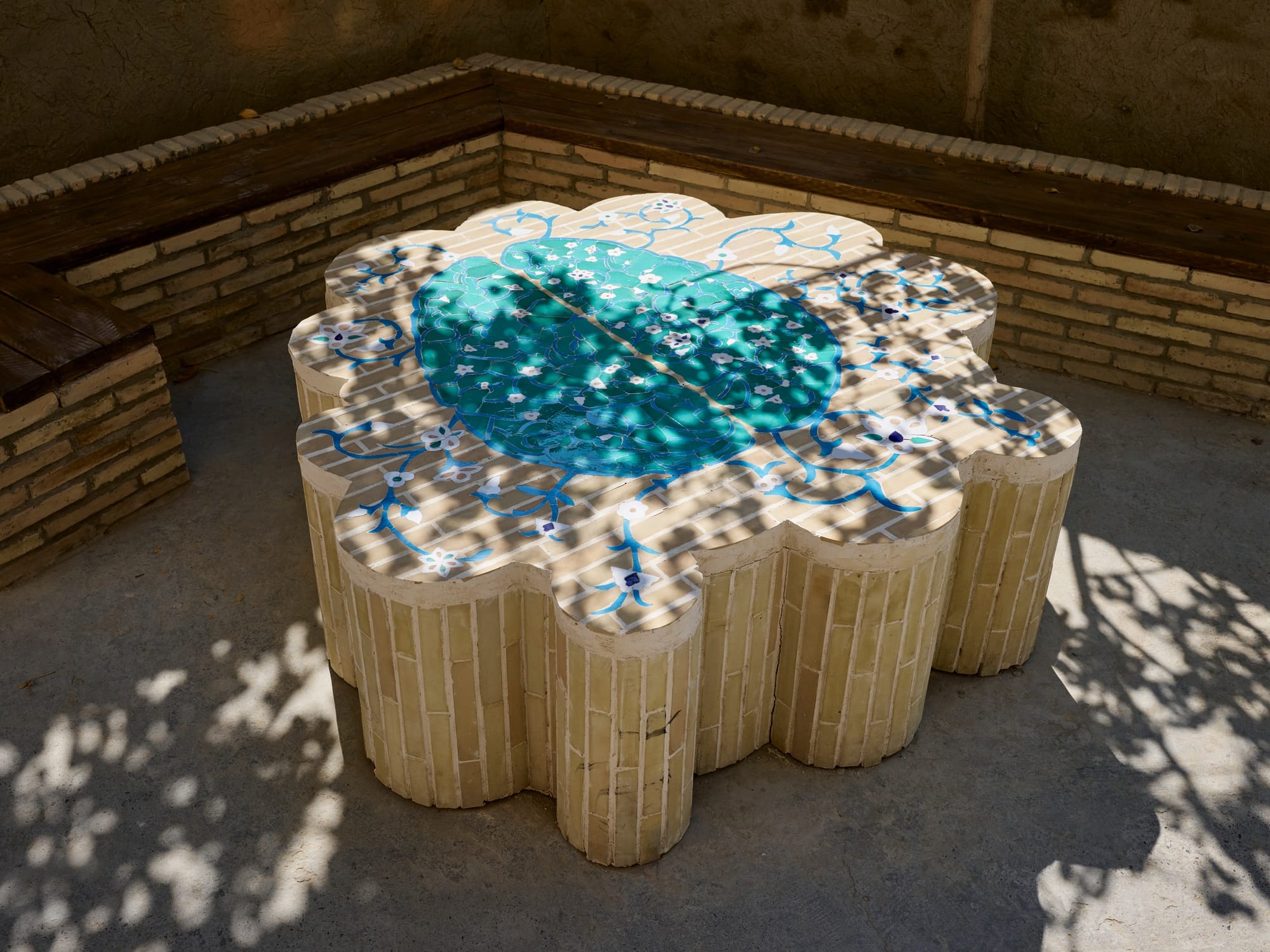

Installation views of OYJON KHAYRULLAEVA’s Eight Lives, 2024–25, in collaboration with RAXMON TOIROV and RAUF TAXIROV, at the Bukhara Biennial, 2025. Photo by Andrey Arekelyan (left) and Adrien Dirand (right). Courtesy the artist and the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, Tashkent.

A bit later, I created the lungs and dedicated it to my mother who suffers from asthma. I would get terrified every time she had an attack, so it was like a wish for her lungs to be healthy and “in bloom.” It also points to the environmental issues in Uzbekistan, where the air quality is terrible due to constant construction, vehicle density, and the burning of tires, coal, and mazut to heat greenhouses outside the cities.

After finishing the lungs, I thought, “why not create all seven vital organs?” Right around that time, I received an invitation from the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation and Diana Campbell to participate in the biennial. During our conversation, Diana and I already knew what I would be creating for the exhibition.

I studied the anatomy of the organs very carefully, and each one took a long time to complete. Strangely, whenever I worked on a particular organ, I would experience physical issues related to it. For example, while constructing the brain, I had problems with my nervous system, including seizures and slowed movement on the left side of my body, which happened exactly when I was working on the left hemisphere. I had to pause for a month and seek treatment. Once I recovered, I was able to return and complete the right hemisphere.

If you look closely, the two hemispheres are drastically different. While the left has very few flowers, the right is organic and blooming. I considered redoing the left hemisphere but decided to leave it as is, to show how the brain affects our outward functioning when something inside isn’t well. Maybe all these health issues emerged because of psychosomatics while I was working on the organs.

Diana and I tried to place the organs in locations where they would carry symbolic meaning. For instance, the heart, which is considered the body’s main organ, was placed in the caravanserai, the main venue of the biennial, since the heart is considered the body’s main organ.

The lungs were installed in the Gavkushon Madrasa because the space itself already “breathes.” Four old mulberry trees grow there, almost extending the work of the lungs by giving shade, coolness, and most importantly, oxygen. They make the courtyard feel alive and pulsing.

The kidneys were placed next to the old canal, referencing their role in keeping the water moving in the body.

The stomach and intestines were installed in Café Oshqozon, since “oshqozon” in Uzbek means “stomach” and literally refers to the “cauldron of plov,” an iconic Uzbek cooking vessel.

The brain was placed near the Khoja Kalon Mosque, because the brain is our connection to God. Interestingly, spiritual experiences really are linked to activity in several parts of the brain: the parietal lobe, the frontal lobe, and the periaqueductal gray matter. The site itself is very tranquil; under the trees, you can sit with friends or by yourself and let your mind wander and philosophize. That was the vibe the place gave me when we first saw it.

The liver was placed in the Rashid Madrasa, because the space carries an inherent sense of healing. It has the atmosphere of a peaceful refuge, a place where you can pause, exhale, and give yourself time to recover. That’s exactly what the liver does in the body: an almost invisible but vital kind of work. It cleans the blood, filters out what can harm us, and has an extraordinary ability to regenerate. It’s one of the few organs that can truly restore itself and begin again. It’s about cleansing, inner processing, gathering strength, and quiet but powerful healing, making the Rashid Madrasa a perfect fit: it is a place where the unnecessary falls away and the essential comes back together.

How was your experience working with Raxmon Toirov and Rauf Taxirov to produce the installation? What were the main challenges, and how were they resolved? Is the final artwork what you envisioned in the beginning, or were there any surprises?

Working with them was very successful, even though they hadn’t received commissions like this before. When I first visited their workshop, I was really nervous they might not agree to the project, because my inspiration was completely outside the classical canons despite stemming from Islamic mosaic tradition. Thankfully, they really liked the concepts and don’t mind experimentation, so they accepted the collaboration gladly.

Our main challenge was to produce the correct gradient of green. I needed a very specific shade, and many samples were made before I finally approved one. Aside from that, everything was excellent. I was amazed by their craftsmanship. They translated my collages into the mosaics exactly, down to the smallest details.

Eight Lives has been very well received in the press. As an artist, could you please comment on what was special about the Bukhara Biennial as a platform for your practice?

What made the Bukhara Biennial special for me is that it was hosted in my hometown. Here is where I spent my childhood, and where my life and artistic career began. This is my first major international exhibition, and participating in it was especially important to me. In addition, all my inspirations come from the atmosphere of Bukhara—its calmness, the Sufi vibes, and stories of the city and my family. All of these keep nourishing my creativity.

More generally, what was your overall experience of the Bukhara Biennial, and how do you feel it impacted the Uzbek art scene? Do you have any suggestions for the next edition?

My experience was incredible. It was my first project on this scale, and everything was completely new. I was learning, observing, and experiencing. It was so intense and impressive that my head is still spinning.

As for its impact on the Uzbek art scene, I think it’s positive, especially for the people of Bukhara, many of whom are encountering contemporary art for the first time. The biennial evoked a wide range of emotions, from surprise and admiration to confusion and even protest. And that’s a good thing, because art should provoke emotions. For the younger generation, this is especially important, since there are unfortunately very few contemporary artists in Bukhara. I hope the biennial would help inspire and motivate a new generation of creators.

Regarding suggestions for the next edition, it’s hard for me to speak on behalf of everyone. Much depends on the curators and their research. I am curious to see what ideas they bring, and I’m sure each new edition will reveal something unique.

As a young Uzbek artist, what challenges have you navigated in your practice generally? What main themes or ideas would you like to continue exploring in the future?

It used to be much more difficult with contemporary art in Uzbekistan. There were almost no galleries, studios, or art spaces; artwork sales were rare; and support through programs and grants was almost nonexistent. Now, the situation is gradually changing. New spaces, initiatives, and opportunities for young artists are emerging, which is very encouraging. Of course, there’s still much to develop, but you can already feel the progress, and that inspires me to keep working and creating.

I would like to continue working on the theme of the human body, as there are still so many unexplored territories and possibilities for new works. This idea excites me and ignites a real spark within me, I feel that I must develop it. I already have many ideas in mind, but for now I’ll keep them to myself. Perhaps you’ll see them in the future.

Chin-chin Yap is a Singaporean writer and filmmaker based in Lisbon and contributing editor for ArtAsiaPacific.