Shows

The Fisherman and the Woodcutter: Duan Jianyu’s Animal Reckoning

Duan Jianyu

Yúqiáo

YDP

London

Oct 14–Dec 20

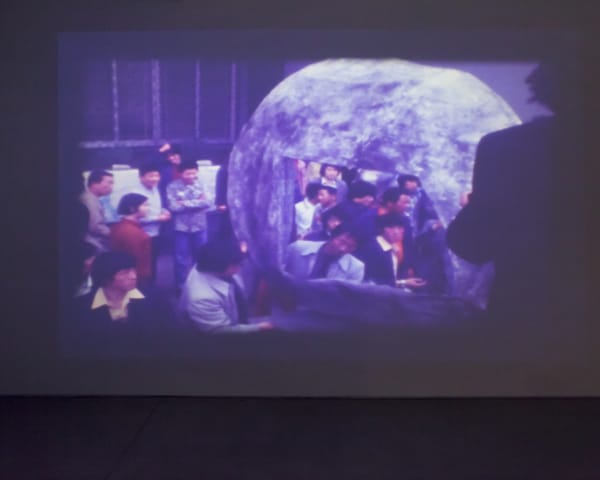

Duan Jianyu paints with a finely honed insouciance—nonchalant, impertinent, yet ultimately tender. Pairing slapdash figuration with ethereally radiant hues, she imbues seemingly casual compositions with a luminous intensity. Her works interlace literary references, pop culture imagery, and subtle social critique, bespeaking an incisive eye, a sprightly sense of humor, and a fierce sensitivity attuned to the weight of the world. In “Yúqiáo,” her first UK solo exhibition in over a decade and the inaugural show at YDP in London, Duan turns to the classical Chinese motif of the fisherman and the woodcutter—reclusive hermits that live in harmony with nature, detached from worldly grit and grime. Reimagining these characters as animals that traverse rural fields, cityscapes, and domestic spaces, Duan’s latest cycle of works craft a moral fable for contemporary existence.

The story begins with a tête-à-tête between a ram and a lamb, a billowing white mass looming in the distance. In Chinese literati, the yúqiáo (“fisherman and woodcutter”) are wise sages who observe society from afar, often appearing as tiny figures in the margins of classical Chinese shan shui hua (“paintings of mountains and waters”). Here, they are recast as anthropomorphic ovines contemplating a meta-representation of a Chinese landscape, an allusion indicated by the orange brocade on the left. Duan’s contemporary shan shui hua features towering cliffs—spray painted with industrial pigment for a deliberately destructive effect—along with a shimmering horizon, deft daubs suggesting trees, as well as a minuscule woodcutter artfully camouflaged in a corner.

Later in the series, the sheep duo reappears indoors. The ram, feet propped on a coffee table, dispenses life lessons, while the lamb breaks the fourth wall with a deadpan gaze. “This is a typical scene of an elderly person lecturing a child,” Duan explains, “but look at the young one’s disdain.” On the far right of the composition, a hanging scroll depicts a woodcutter toiling in the mountains, with two monkeys—symbols of intelligence and mischief in Chinese art—perched on the wood bundle on his back. Alongside her questioning of traditional systems of wisdom and hierarchy, Duan also probes art’s function as a mode of social critique.

“We are all like the yúqiáo in some way,” Duan says, “constantly dissecting worldly matters, or commenting on daily minutiae behind people’s backs. And the yúqiáo, in turn, are just like us. I was inspired by how these archetypal figures are not just saints or philosophers—they are ordinary people rooted in the realities of work, family, and survival, sharing our common human experience.”

DUAN JIANYU, Yúqiáo (The Fisherman and The Woodcutter) No.4, 2023, oil, acrylic, and pencil on canvas, 200 x 140 cm (left); and Yúqiáo (The Fisherman and The Woodcutter) No.5, 2023, oil, acrylic, and spray paint on canvas, 150 x 200 cm (right). Courtesy the artist and Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou.

The yúqiáo thus embody an existence defined by a cyclical interplay of immersion and withdrawal. Much like Zen Buddhism’s balance of engagement with detachment, or Heidegger’s Being-in-the-World embracing openness through Stimmung (“mood”) and Gelassenheit (“releasement”), they sustain authentic presence through perpetual oscillation—a being-in that periodically steps back out. Duan’s shapeshifting characters enacts these rhythms: in Yúqiáo (The Fisherman and The Woodcutter) No. 4 (2023), two fishermen clad in majestic cloaks of fish clusters are engulfed by colossal, gestural waves; while in the subsequent work, they rest ashore beside tranquil waters. Their mantles have metamorphosed into armor-like insect wings, while nearby, spheres of light hover in the twilight, reminiscent of fireflies.

Duan paints in a style known as huai hua (“bad painting”) that emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s. A bizarre bricolage of the raw and the vernacular, her work subverts traditional expectations of taste, with crude imagery and incongruous motifs that are sometimes coded but not always—their absurdity mirroring the contradictions of contemporary life. “I detest refinement,” she states emphatically, referring perhaps to pretense or the strategies of seduction of highbrow idealism. Instead, her garish forms refuse to entice, putting not just the status of the genre at stake but also our fundamental attitudes toward existence itself.

As the series unfolds, its tone grows increasingly, exhilaratingly, macabre. One painting shows chickens eyeing Crocs slippers adorned with ornaments modeled after Kentucky Fried Chicken drummets. Another depicts a musician playing the guqin, a Chinese plucked zither, for a quartet of cows, referencing the idiom dui niu tan qin (“playing the zither to cows”), which conveys the futility of addressing someone unable or unwilling to understand. It transpires that the musician is wielding table knives, which explains the lead cow’s vicious side-eye. In another scene, a thundering herd of sheep advances—defecating with each step—upon a lone figure with his arms outstretched, crucified beneath an apocalyptic sky. “The sheep are interrogating him,” Duan explains of the biblical scene. “They are asking why they were raised just to be slaughtered as food for man.” Adjacent, a smaller painting—selected as the exhibition’s headlining image—features four disembodied heads with contorted expressions, engrossed in country song. Bits of sheep droppings drift like musical notes, breaking free from a floating five-line staff, toward their gaping mouths.

The moral here seems less animal advocacy than a caution against the erosion of lucid existence—of presence, reflection, agency, and responsibility—in a hyper-paced, hyper-automated world. In one of the final paintings, the artist depicts herself squatting naked with her back to viewers, stroking a cat in a cluttered room. The shadowy interior is strewn with empty delivery containers and a large bucket of KFC. With only a sliver of her profile visible, her expression withheld, the scene evokes not just social isolation but a chilling moment of meta-awareness: a split-second rupture in which she pauses—right at the threshold—of apprehending her entrapment in the contemporary condition. The work could be a reversal of an earlier tableau in the show, where a gaunt human skeleton sits front-facing among blooming flowers, its scrawny fingers petting a plump chicken. Duan’s indictment goes beyond mere charges of complicity and complacency to constitute an unequivocal summons: unlike animals, we alone engineered the world as it stands today, and it is up to us to decide its next course.

Michele Chan is managing editor at ArtAsiaPacific.