Shows

Precise Chaos: Sasha Gordon’s Hyperreal Selves

Sasha Gordon

Haze

David Zwirner

New York

Sep 25–Nov 1, 2025

Behind aquarium glass, a woman is drowning at the hands of another. One figure forces another underwater, pressing down on her victim’s head. Floating hair, air bubbles, knees against glass—all rendered with fanatical precision—culminate in a stylized hyperrealistic tableau frozen mid-violence. Both figures in Pruning (2025) are Sasha Gordon—two among many that populated “Haze,” Gordon’s inaugural solo exhibition at David Zwirner. The painting establishes the show’s governing paradox: hyperrealism deployed not to clarify but to proliferate, not to resolve but to overwhelm.

While photorealism promised one-to-one correspondence with reality, Gordon employs hyperrealistic techniques to authenticate what resists authentication. Her exacting brushwork depicts scenarios that defy singular interpretation: horror tableaux from classical mythology, cinema, and personal nightmares position her doubled self as both protagonist and antagonist. Where the technique conventionally promises one truth, Gordon delivers many—each executed with equal conviction, none prioritized as “real.” This multiplication becomes strategic: an overproduction of legible bodies that paradoxically blocks the extraction of a consumable subject.

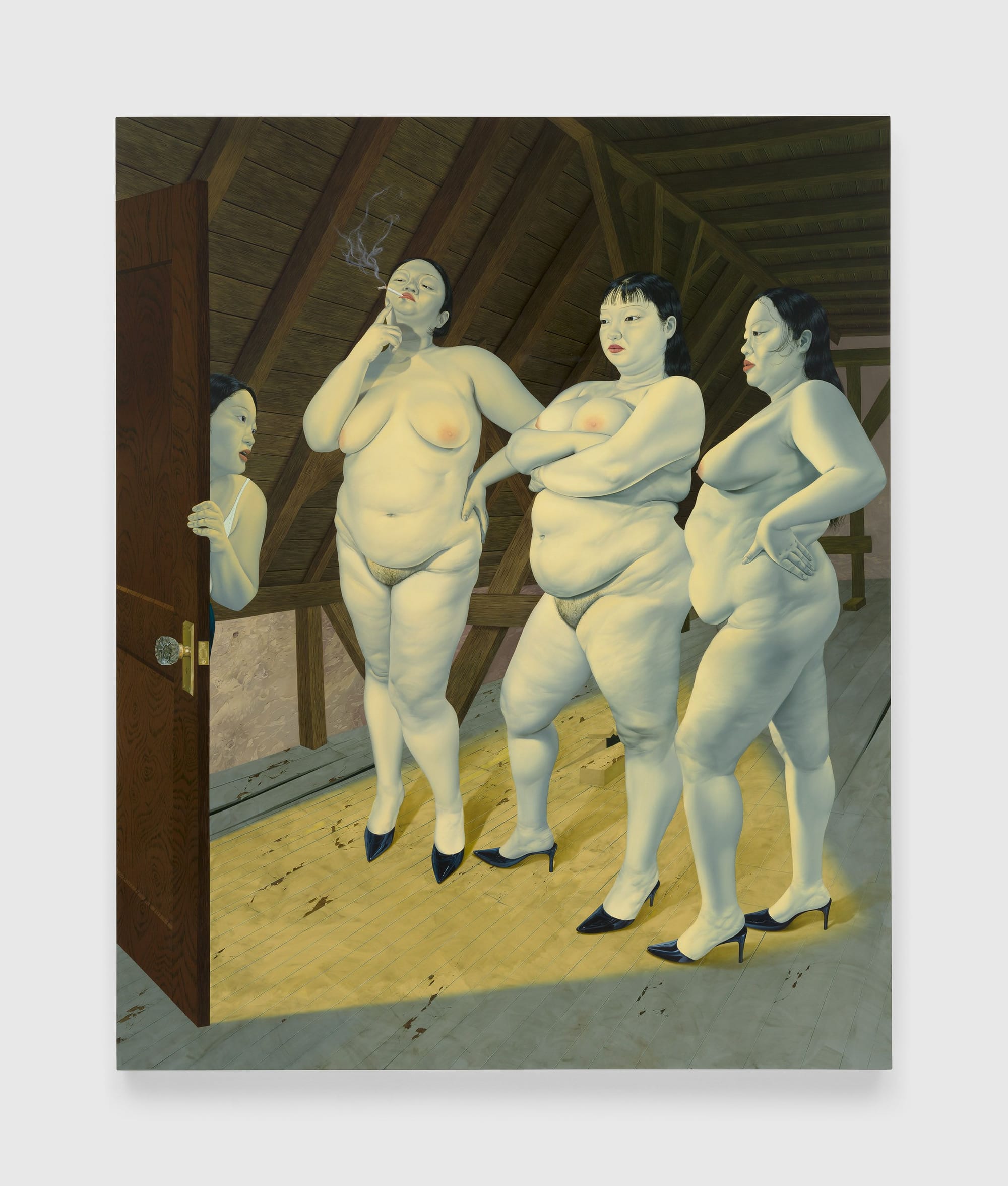

SASHA GORDON, A Visitation, 2025, oil on linen, 213.4 x 182.9 cm (left); and Whores in the Attic, 2024, oil on linen, 244.2 x 198.8 cm (right).

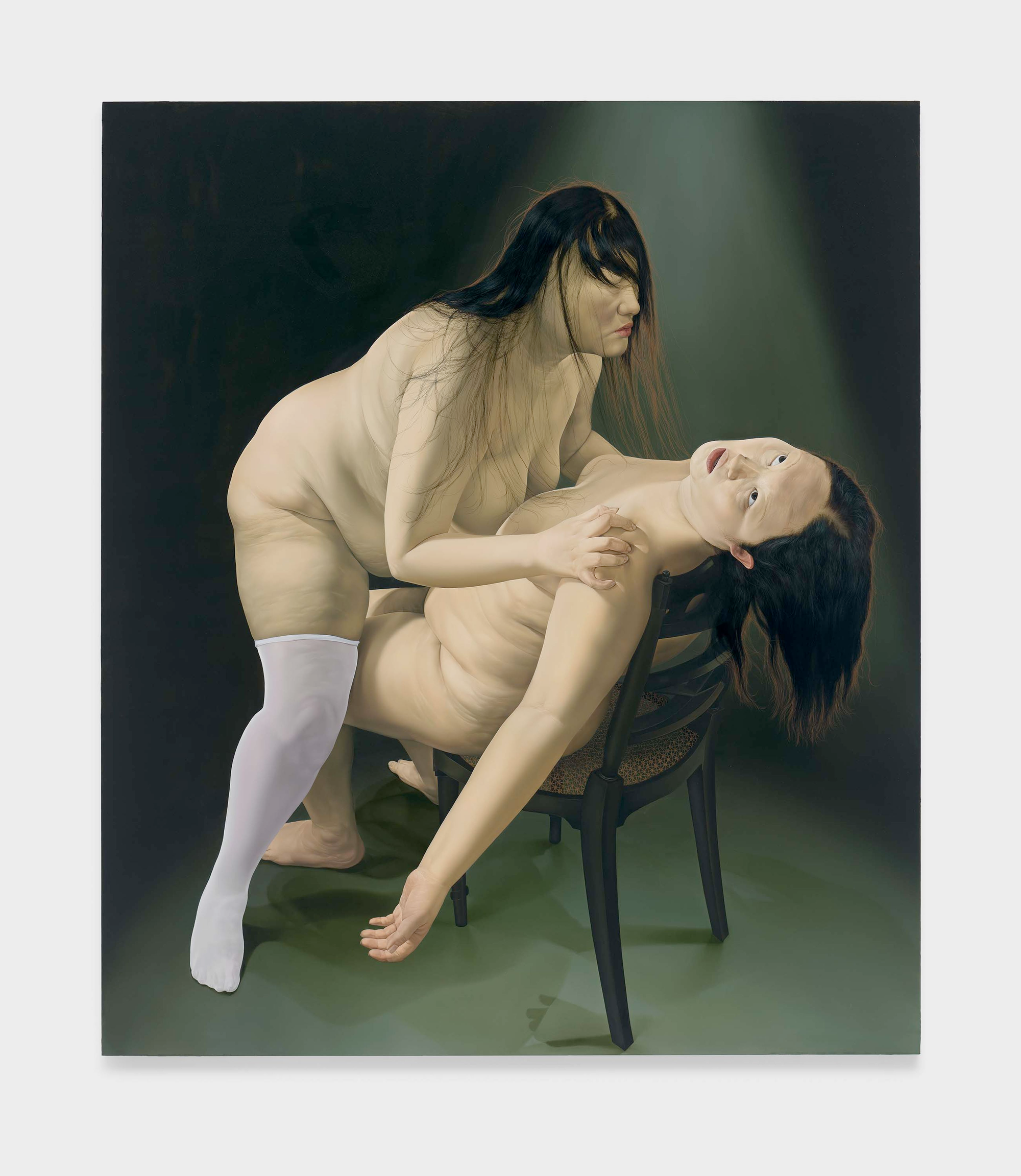

This strategy crystallizes when doppelgänger Gordons meet in lethal combat. A Visitation (2025) stages two figures theatrically spotlighted in darkness: one seated, arching backward in equivocal surrender, while another looms over her with unclear intent—solace or violation? The composition evokes Baroque pietàs while resisting straightforward reading. Gordon’s meticulous execution makes us voyeuristic witnesses to a violence we cannot definitively name, with the fervent level of specificity—every fold of skin rendered—insisting on material reality even as meaning slips between possibilities.

Petrified (2025) pushes ambiguity into visceral entanglement. One Gordon drags another, lying supine, across rough ground. What initially appears as rope reveals itself as braided pubic hair—ambiguously functioning as umbilical cord or leash, connection or restraint. The dirty, smeared faces, captured in fastidious detail, remain emotionally unreadable. These bodies exist as facts—weight, texture, palpable tension—yet their relationship evades comprehension.

Where some paintings stage intimate encounters, others veer toward cacophony. Whores in the Attic (2024) crowds four Gordons within a shadowy attic. Three figures, nude except for black heels, arrange themselves in a formation suggesting both conspiracy and confrontation. A fourth figure in a tank top lingers at the door, her expression hovering between wariness and longing. Husbandry Heaven (2025) deploys a similar cast in black heels, but with only two appearing fully in the frame. One feeds another, the title framing husbandry as tender violence, cultivation as control. Gordon floods her canvases with protagonists, antagonists, and witnesses—roles that shift with each viewing, rejecting stable narratives.

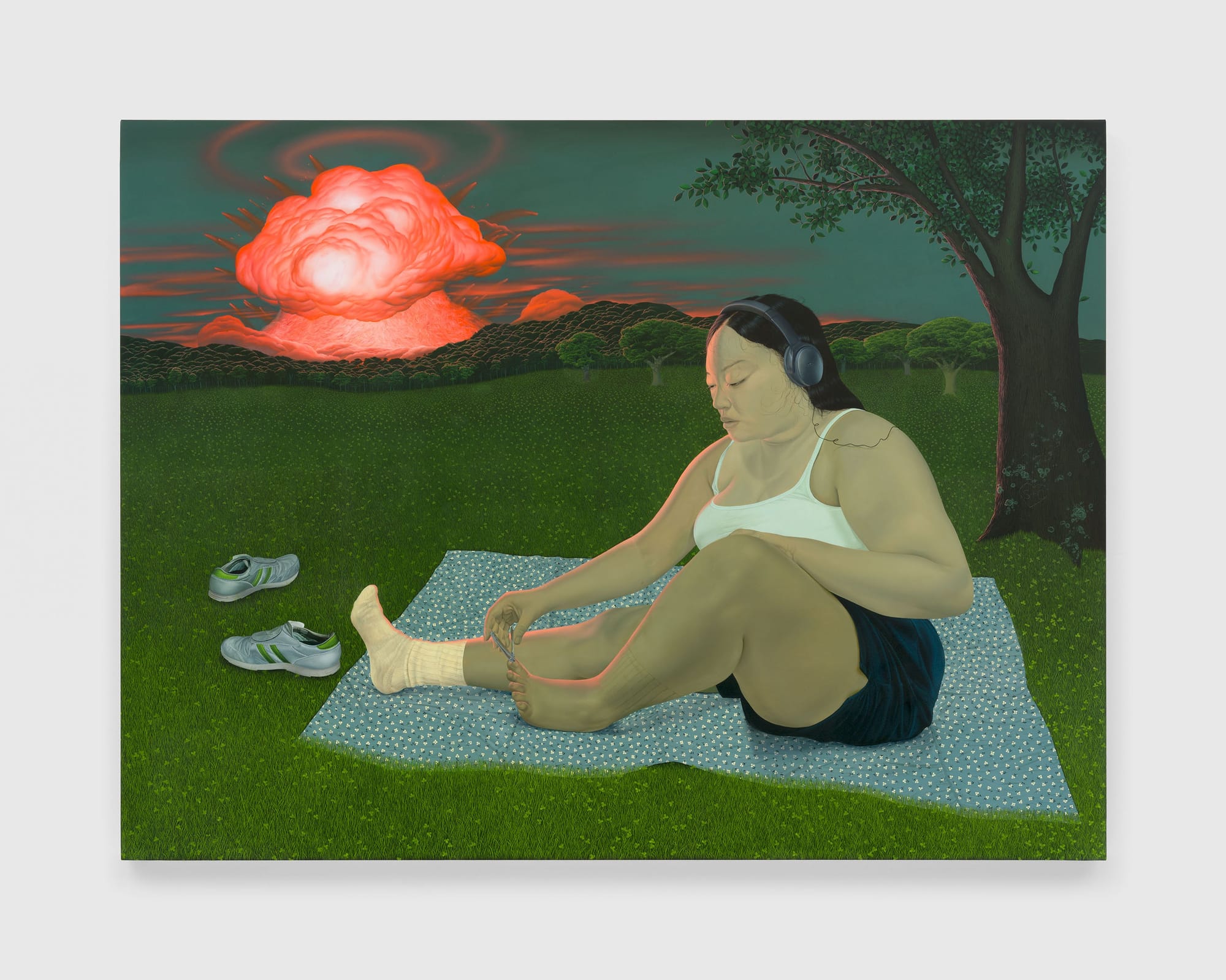

It Was Still Far Away (2024), featuring a solitary Gordon, offers a crucial counterpoint through isolation. The protagonist lounges on a picnic blanket, headphones on, clipping her toenails. Behind her, an apocalyptic explosion tears through the sky. Even as the blast stains her skin red, she remains unmoved. Her calm is not denial but radical presence—a body refusing to perform crisis on command. Sometimes endurance manifests as stillness; survival might mean declining the prescribed script.

Such refusal emerges from Gordon’s identity as a mixed-race, Asian American queer woman navigating institutions demanding legibility. Rather than choosing between being consumable and categorizable or withdrawing entirely from view, she inundates our vision with selves that multiply beyond coherence, and with obsessive detail that confounds. Gordon weaponizes the very precision of hyperrealistic techniques to fracture—rather than fortify—the illusion of congruent selfhood.

The exhibition title operates on several registers. “Haze” describes the violent hazing rituals depicted in the paintings, while evoking the disorientation viewers experience when faced with interpretive opacity despite forensic visual clarity. Through months of layered oil paint—each wrinkle and hair receiving equal attention—Gordon builds conditions where resolution becomes structurally impossible, each painting teeming with visual information while denying conclusive reading.

In a moment when marginalized subjects face both hypervisibility and erasure, Gordon transforms withholding into formal strategy. She paints herself drowning and enduring, multiplying and petrifying, occupying bodies and consciousnesses that dissociate, splinter, and shift between roles. This calculated incoherence bends hyperrealism toward resistance, where documentary precision serves not to fix but to destabilize. Gordon employs the master’s tools not just to dismantle the master’s house but to build something more unsettling: a space where the self proliferates beyond recognition, witnessed in excruciating detail yet never captured, never owned.

Ho Won Kim is a Seoul-born, New York-based curator and writer.