Shows

Pineapples, Migrant Workers, and Pearls of the Orient: Stephanie Comilang at CARA

Stephanie Comilang

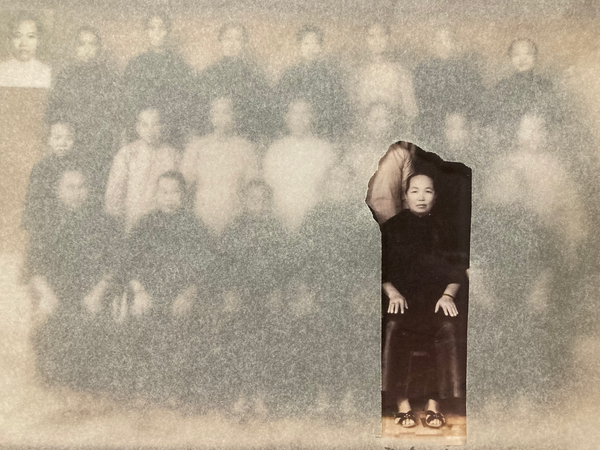

An Apparition, A Song

Center for Art, Research and Alliances / CARA

New York

May 31–Aug 10, 2025

The first solo exhibition in the US of Berlin-based Filipina Canadian artist Stephanie Comilang at the Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA) felt timely. Amid challenges such as ICE raids and visa denials to what was once upheld as modern, progressive values in the American Dream, Comilang’s “sci-fi documentary” installations extracted the capitalist and postcolonial realities of diasporic lives across continents. Her Odyssean narratives poignantly traverse histories, geographies, and trades, mirroring the stark contrast between New York’s elite and migrant workers seeking minimum-wage jobs.

CARA, a radical nonprofit located in Manhattan’s West Village opposite the LGBTQ Community Center, hosts programming and publication offerings that align with the neighborhood’s artistic and activist spirit. Comilang’s exhibition, organized by Rahul Guidipudi, added to this intellectual atmosphere. The three works in the exhibition, previously shown at Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun in 2019, Tate Modern in 2022, and the Sharjah Biennale this year respectively, were presented together for the first time, providing more context for Comilang’s quasi-journalistic eye and ambitious stories.

On the ground floor was Piña, Why is the Sky Blue? (2022), a collaboration with German Ecuadorian artist Simon Speiser. The immersive installation weaves the transnational histories of the piña, or pineapple, through film, black-and-white 3D printing on handwoven fabric, a VR experience, and digitally generated patterns on giant floor cushions. The film juxtaposes interviews with women activists and spiritual healers in Ecuador and the Philippines against footage of lush landscapes and rituals. In tracing the traumatic history of displaced peoples in Latin America due to the slave trade, Comilang explores how the Spanish brought pineapples from South America to the Philippines while also examining shamanistic healing practices. The film’s woo-woo segments, I later determined, reflect parallel developments on both sides of the Pacific shaped by Spanish colonial forces, and are not directly related to piña, a name coined by Christopher Columbus based on the the fruit’s resemblance to a pine cone.

Comilang’s examination of piña and its socioeconomic impact reminded me of the 2021 pineapple embargo between mainland China and Taiwan. Growing up in Taiwan, I took for granted its role as a regional producer and exporter of tropical fruits—including pineapples—and as the origin of the beloved Taiwanese pineapple cake, never realizing that pineapples are not native to Taiwan. The 2021 embargo sparked strong demand in Hong Kong and Japan for Taiwanese Golden Diamond Pineapples, praised for their exceptional sweetness and juiciness. Echoing the narrative in Comilang’s Piña, pineapples made landfall in Taiwan in the early 1600s, brought by the Portuguese via Macau and mainland China, as observed by David Wright, a Scottish agent of the Dutch East India Company who lived on the island during Dutch colonial rule in the 1640s.

Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come to me, Paradise) (2018) on the second floor was at once the most accessible and most complex in the show. Across a three-channel projection, a drone captures the POV of three Filipina domestic workers in Hong Kong, narrating a story of isolation through haphazardly filmed footage of their gatherings in Central, near City Hall. The gallery’s floor and walls were covered with flattened cardboard boxes locally sourced from New York, mimicking the practice of migrant workers in Hong Kong using them as makeshift shelters and seating mats in public spaces on their days off. In New York, where cardboard boxes are more associated with homelessness, the installation might have resonated differently—but perhaps homelessness is what an onlooker gleans from these scenes in Hong Kong. Typically living in tiny rooms connected to their employers’ kitchens, Southeast Asian domestic workers in Hong Kong spend public holidays hanging out under overpasses, in parks, and on beaches—places they can stay without cost. With their lodgings in Hong Kong belonging to their employers, their true homes are seen only through video calls with family.

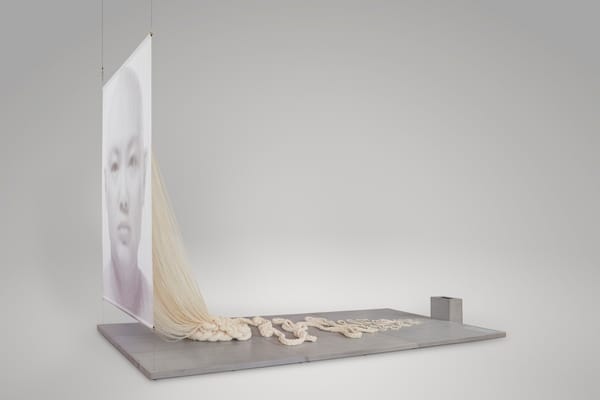

The last and most recent work, Search for Life II (2025), demonstrates a more mature approach to both presentation and storytelling. Chronicling the epic tale of the pearl trade across Asia and of the Asian diaspora in the UAE, the work is projected on the wall through a screen comprising artificial pearl-like beads, creating two layers of moving images. The film features pearl diving families in the Philippines and a village in China where workers clad in Wellies and plastic ponchos shuck truckloads of oysters for pearls. Alternating with scenes of those involved in pearling are interviews with young, middle-class Emirati women of mixed heritage, dressed in coordinated outfits like a K-pop girl group. They sing, dance, and discuss identity politics and their experiences growing up in the Emirates, a region that gained international attention through the pearl trade prior to the discovery of oil.

The varied themes in Comilang’s works in the exhibition reveal a singular focus—the lives of Philippine people and diaspora across centuries—and provoke reflections on broader global issues. The Gulf States, with their rapid economic ascension in the last two decades, have become hubs of diaspora like the US and Hong Kong, relying heavily on skilled English-speaking labor from South and Southeast Asia. Behind the gleaming façade of modern architecture, luxury goods, and other conveniences in these cities lie stories overlooked in the name of progress that Comilang threads together.