Shows

Paradise Should Exist Within You: Bukhara Biennial

Bukhara Biennial

Recipes for Broken Hearts

Sep 5–Nov 23, 2025

The ancient city of Bukhara was established around 500 BC, almost a thousand years before Venice. These early, cosmopolitan centers of trade and culture, 4,200 kilometers apart, would eventually be linked by the great overland network of the Silk Road, fostering extraordinary artists, inventors, and explorers, while their rulers and patrons fashioned legacies through monumental works of architecture. Today, Bukhara is attempting to follow Venice’s contemporary soft power strategy to establish itself as a hub for culture and heritage tourism. It has made an impressive debut with the Bukhara Biennial, the jewel in the crown of Uzbekistan’s Arts and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF)’s zealous enterprise.

Established by Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev in 2017, ACDF is helmed by Gayane Umerova, its eloquent and energetic chairperson who represents her country at UNESCO and commissions the Uzbek pavilions in Venice. Of art as an instrument of cultural diplomacy and soft power, Umerova said directly: “We see it as a tool and we use it as a tool.” In Tashkent, ACDF has overseen the recent partial unveiling of the Centre for Contemporary Art in September (it will fully open to the public in March 2026) as well as the forthcoming Tadao Ando-designed National Museum, due to launch in 2028. It also spearheads the critical discourse around preservation and contemporary use of Tashkent’s modernist architectural gems, and is behind two sleek scholarly publications on the topic. Notably, UNESCO’s 43rd General Conference took place in Samarkand from October 30 to November 13, its first venue outside of Paris since 1985.

The inaugural biennial’s artistic director is Diana Campbell, who has worked extensively with South Asian art through the Dhaka Art Summit and Samdani Art Foundation. Campbell’s decolonial sensibilities are evident in her ambitious curatorial program titled “Recipes for Broken Hearts,” which draws upon the historic Islamic city’s rich artistic, intellectual, and scientific legacies as sources for contemporary interventions imagining fragments of a new world. Almost all of the 200-plus participating artists have Global South roots. Campbell’s staunchly democratic program sets Uzbek creatives squarely on equal footing alongside their international counterparts: all foreign artists collaborated in some form with local artisans and craftspeople to produce site-specific works, a feel-good strategy that is actually grounded in substance, showcasing Uzbek expertise and traditions in mosaic, textiles, miniatures, and ceramics. Both artist and artisan are equitably credited for the work—a welcome recalibration that, as Campbell’s curatorial statement puts it, seeks to “heal unjust divisions between how we see fine and applied arts and how we talk about collaboration.” The emphasis on craft might be seen as legerdemain to sidestep more overt political offerings, but here the intimate and exceptional caliber of execution registers as a different kind of political act, seeking to lay the foundations of a new epoch rather than parachuting a predictable roster of biennial favorites in and out.

Installation view of HYLOZOIC/DESIRES (Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser)’s Longing, 2024–25, in collaboration with RASULJON MIRZAAHMEDOV (Margilan Crafts Development Centre), at the Bukhara Biennial, 2025. Photos by Felix Odell. Courtesy the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, Tashkent.

Lebanese architect Wael Al Awar has thoughtfully restored Bukhara’s caravanserais, madrasas, and mosques with an eye for the biennial’s site-specific installations, many of which engage with time, space, and human endeavor to provoke our deeper curiosity about the city’s intellectual and scientific history. Like Venice, Bukharan life once revolved around a citywide canal network, which is now elegantly highlighted by Longing (2024–25), a spectacular ikat tapestry installation by the performance duo Hylozoic/Desires in collaboration with Rasuljon Mirzaahmedov (founder of the Margilan Crafts Development Centre). Tracing the canals throughout the exhibition sites, the tapestry’s patterns are based on satellite imagery of the Aral Sea, a climate fiasco precipitated by large Soviet-era water diversion projects. Meanwhile, Brazilian artist Marina Perez Simão’s imaginary celestial mosaic map on a caravanserai floor—created in collaboration with Uzbek mosaic artist Bakhtiyar Babamuradov—references Samarkand’s pioneering 15th-century innovations in astronomy.

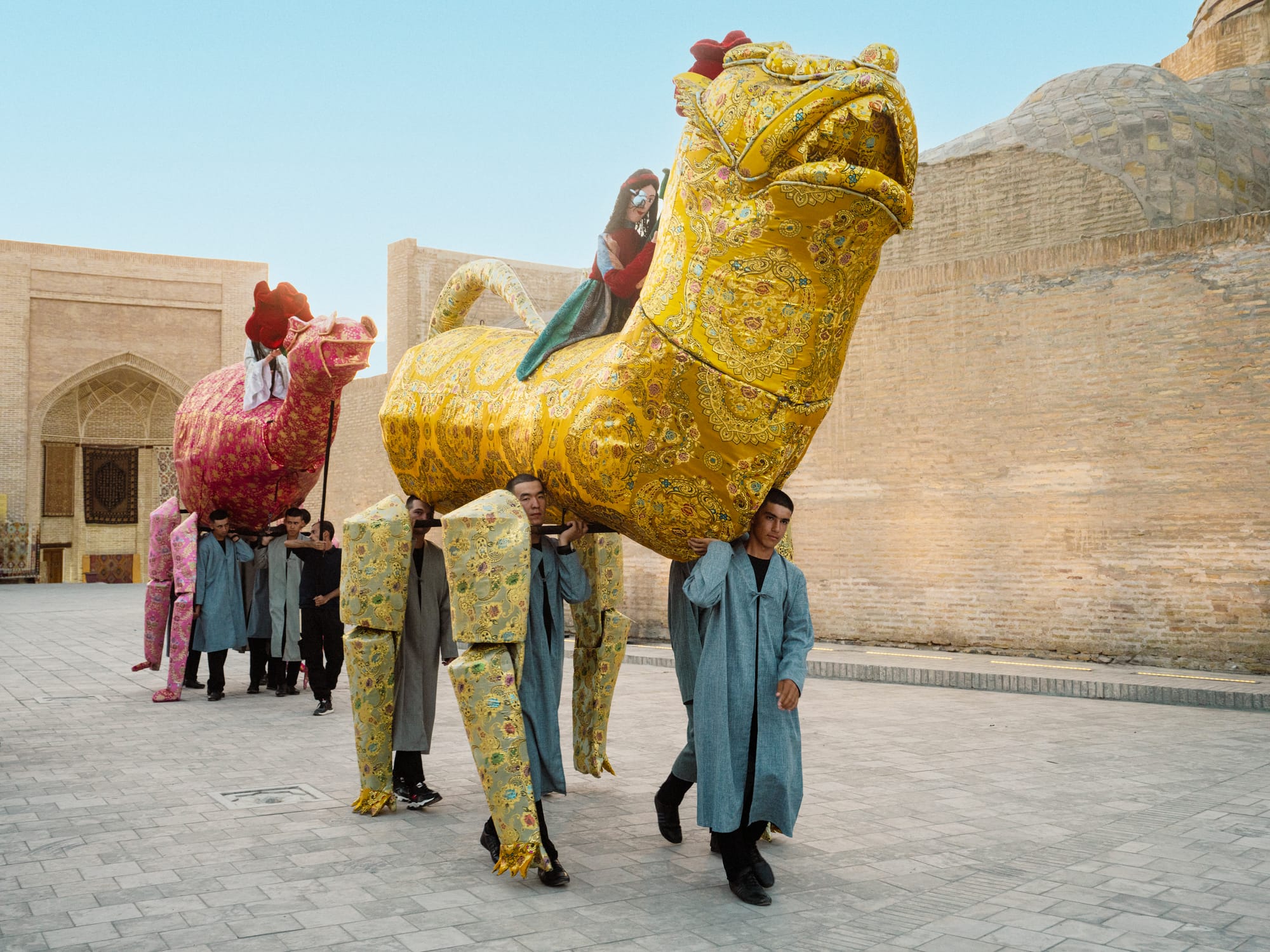

Sufism—the Islamic school of mystic practices focusing on spiritual purification—is a key concept charging the event with an exhilarating, organic flow befitting Bukhara’s stature as a historic center for Islamic theology. One of the most popular performances was Bangladeshi artist Kamruzzaman Shadhin’s Safar (Journey) (2025), a magnificent collaboration with the Uzbek puppet master Zavkiddin Yodgorov and the Gidree Bawlee Foundation for the Arts. They rendered a larger-than-life coterie of mythical animals in shimmering traditional brocade—a cherry-red dromedary, metallic yellow lion, jade green crocodile, purple horse, and a navy and gold fish—each carrying a Sufi mystic. During the biennial’s opening these oversized puppets paraded through the streets of Bukhara, symbolizing Sufism’s spread across Central Asia. Eventually, the puppets turned out so heavy that they had to be carried by Uzbek military staff.

Another crowd-pleaser was 29-year-old mixed-media artist Oyjon Khayrullaeva’s Eight Lives (2024–25), produced in collaboration with local mosaic artisans Raxmon Toirov and Rauf Taxirov. Eight bodily organs are rendered in oversize, colorful mosaic sculptures and strategically scattered around the biennial’s various sites with specific evocations of refuge, cleansing, regeneration, and spirituality. Khayrullaeva explained that this important work arose from three connected ideas: her visit to the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis in Samarkand, the connection between mental and physical health, and the Sufi concept of Jannah al-Firdaws which “sees paradise not as a distant promise, but as a quiet inner garden, a state of a cleansed heart where pain turns into light.” 30 percent of Uzbekistan’s 38 million population is under 14 years old, and it is heartening that several of the biennial’s standout works are by young Uzbek artists such as Khayrullaeva. During the press tour, Campbell highlighted one of her favorite works, the installation A Corner For Everyone (2024–25), made by the 24-year-old Tashkent-based artist Zi Kakhramonova in collaboration with the London-based Bukharian chef Lilian Cordell. Set in a caravanserai’s spacious, sunken outdoor pit, the work is best described as a playground for adults and children alike, stocked with vibrant fabric cushions in traditional textiles referencing Uzbek domestic designs.

Perhaps the most Instagrammed area is the austerely theatrical Khoja Kalon mosque that one approaches through Colombian artist Delcy Morelos’s La Sombra Terrestre (The Earth’s Shadow) (2024–25), produced in collaboration with Uzbek artist Baxtiyor Akhmedov. A majestic jute pyramid solidified with a concoction of cinnamon, cloves, turmeric, sand, and clay, the work is partially adjoined to the mosque’s columns, like some sensuous alien portal settling on earth. Upon exiting, one encountered the somber, cemetery-like field of British sculptor Antony Gormley’s CLOSE (2024–25), a group of his recognizable geometric figures, but this time fabricated in mud by Bukharian restorer Temur Jumaev. Beyond this was The Observer’s Illusion (2025), an exquisite, gently rising sand dune by two floral artists, Tashkent-based Ruben Saakyan and Kemerovo-based Konstantin Lazarev. At first glance the work appears as a minimalist background for Gormley’s work; climbing the dune, one emerged onto a slender ribbon of ferns, wild grasses, and sprouting flowers unfurling on the far side—an untamed oasis that literally breathes life into an otherwise ascetic setting.

Installation views of ANTONY GORMLEY’s CLOSE, 2024–25, in collaboration with TEMUR JUMAEV (left); and DELCY MORELOS’s La Sombra Terrestre (The Earth’s Shadow), 2024–25, in collaboration with BAXTIYOR AKHMEDOV (right), at the Bukhara Biennial, 2025. Photos by Adrien Dirand. Courtesy the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, Tashkent.

Reflecting the state’s careful maneuvering between the superpowers of China, Russia, and the US, the biennial featured few overtly political works. There were no artists from the Congo, Sudan, or Ukraine. The one exception seemed to be Palestinian Saudi artist Dana Awartani, whose Standing by the Ruins IV (2025), a collaboration with Uzbek artisan Behzod Turdiyev, uses Palestinian clay to construct geometric motifs from Gaza’s ancient healing spa, the Hammam al-Sammara (“Bath of the Samaritans”), which was destroyed in 2023 by an Israeli airstrike. Another prescient absurdist work is Qatari filmmaker Majid Al-Remaihi’s A Donkey Will (2025), created together with Indonesian-Saudi-Yemeni artist Anhar Salem and Uzbek puppet artist Iskandar Hakimov. In a contemporary spin on the beloved folktale of the “holy fool” Nasreddin and his donkey, the dual-channel video depicts the two separated and searching for each other on the streets of Bukhara.

By the time of its closing, the biennial drew 1.8 million visitors, 55 percent of whom were Uzbek and including many Bukhara residents. Those figures are remarkable considering that the (ticketed) Venice Biennale attracted 700,000 visitors in 2024. This generosity of spirit was evident in the palov parties and local attendees that raucously closed out the event. One evening recreated the Bukharan emir’s palov contests with 10 versions from different Uzbek regions; another featured rice-based cuisine from around the world, including Brazilian, Indian, Korean, Peruvian, and West African dishes. Both nights were packed with DJ sets, local teenagers forming conga lines, and groups of Uzbek families, teenagers, and toddlers.

When the Venice Biennale’s inaugural edition took place in 1895, it revived an ailing city whose fortunes had declined disastrously under Napoleon. Today, Bukhara faces its own unique challenges in terms of heritage preservation and sustainability. It was recognized as a UNESCO heritage site in 1993, deemed “the most complete and unspoiled example of a medieval Central Asian town which has preserved its urban fabric to the present day.” However, like Venice, Bukhara’s architectural structures suffer from underground water erosion and salinity; many older buildings have visible wooden layers over their foundations protecting the upper structures from water damage. While most observers favorably compared Bukhara’s carefully managed tourism to Samarkand’s more laissez-faire approach, it remains uncertain if Bukhara can avoid the familiar fate of Venice—overtourism and a thinning population. Two four-star hotels, the Wyndham and Mercure, opened in 2022 and 2023 respectively, and by the end of 2026 a new international airport is slated to replace the existing aerodrome, expanding its currently limited connections to Istanbul and several Russian cities.

A familiar (and important) point of contention is Uzbekistan’s bleak human rights record, which is either entirely absent from glowing reviews of the biennial or, conversely, used as the sole pretext for undermining the project’s legitimacy. While we should certainly resist threats to artistic freedom everywhere, it is equally critical to reject double standards and moral grandstanding that often mask Western neoliberal perspectives and their updated orientalist playbooks. Nobody would think, for example, to question the legitimacy of art production, exhibition, or appreciation in Europe or the US despite their widespread censorship, cancelations, and even police brutality against artists, activists, and citizens demonstrating solidarity with Palestinians during the recent genocide. It is also disingenuous to ignore the specificities of developing nations’ historical trajectories, particularly those grappling with pivotal transitions from imperial pasts to steer their states through today’s fast-changing realpolitik. Besides, what is the realistic alternative: to deny Central Asia’s fastest growing economy of more than 38 million people the opportunity for their culture to emerge on the global stage? Grousing about Uzbekistan’s successful soft power play? Flip back to those dog-eared, liberally annotated chapters on the Medicis and the CIA, please.

Any realistic critique of the Bukhara Biennial must be grounded in the geopolitical dynamics of the contemporary Silk Road, in which the objects of desire are no longer silk and spices, but rather oil, gas, minerals, rare earth elements, strategic alignments, and security assurances. Just weeks before the biennial’s closing, Donald Trump signed a USD 34.5 billion trade deal with Uzbek president Shavkat Mirziyoyev and presided over the first-ever C5+1 summit at the White House, bolstering the US’s security and economic cooperation with Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. These deals were cut in the wake of the US-China trade war and China’s new restrictions on rare earth elements, some of which have been recently discovered in Central Asia. Oyjon Khayrullaeva, the Uzbek artist who eloquently spoke about the Sufi concept that “paradise should exist within you,” also noted that the biennial “evoked a wide range of emotions, from surprise and admiration to confusion and even protest. And that’s a good thing, because art should provoke emotions.” In Bukhara—as in Abu Dhabi, Sharjah, Shanghai, and São Paulo—a muscular multipolar world emerges as the sun sets on the frayed empire of American-led exceptionalism. Its best recipe for broken hearts may simply lie in shedding dusty habits and facing this new world with an open mind.

Chin-chin Yap is a Singaporean writer and filmmaker based in Lisbon and contributing editor for ArtAsiaPacific.