Shows

On Not Knowing: 15th Shanghai Biennale

The 15th Shanghai Biennale opened with a simple query: “Does the flower hear the bee?” The title drew from research conducted by scientists at the University of Turin, which uncovered that plants can “hear” the buzzing of bees and respond by secreting more nectar when pollinators approach. Explaining her curatorial framework, chief curator Kitty Scott recounted how this scientific finding prompted her to reconsider our relationship to Indigenous modes of knowing, the natural world, and human sensorial faculties. In an era dominated by the accelerationist logic of technological progress and productivity, what is the role of the senses, of tactile awareness? Following this directive, the biennale proposed sensory attunement as a way of making sense of the world.

Such attention to the nonhuman agency is hardly novel. The curatorial premise echoed thoughts from ancient Eastern philosophy—such as Zhuangzi and Huizi’s debate about understanding the “joy of fish”—to contemporary Western thought (Bruno Latour’s parliament of things, Donna Haraway’s companion species, and Timothy Morton’s hyperobjects, to name a few). Arguably, the biennale’s interrogative title aligned more with anthropologist Eduardo Kohn’s influential study How Forests Think (2013), which propounds that “encounter[ing] other kinds of beings forces us to recognize the fact that seeing, representing, and perhaps knowing, even thinking, are not exclusively human affairs.” Though the theme addressed prevalent concerns in contemporary art, such as the limitations of human knowledge, the interconnectedness of all things and beings, the question remains whether art—as a manifestation of human creativity, thought, or craft—can genuinely engage nonhuman experience.

Installation views of ALLORA & CALZADILLA’s Penumbra, 2020, andPhantom Forest, 2025, at the 15th Shanghai Biennale, Power Station of Art (PSA), 2025. Copyright Allora & Calzadilla. Courtesy the artist, Lisson Gallery, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Kurimanzutto, and PSA (left); and HAEGUE YANG’s Accommodating the Epic Dispersion - On Non-Cathartic Volume of Dispersion, 2012, aluminum venetian blinds, powder-coated aluminum hanging structure, steel wire rope, at the 15th Shanghai Biennale, PSA, 2025 (right). Courtesy the artist and PSA.

Upon entering the Power Station of Art (PSA), visitors first encountered Allora & Calzadilla’s Phantom Forest (2025) hanging in the cavernous first-floor atrium. The work featured thousands of yellow synthetic petals hovering midair—rootless, branchless, suggesting remnants of a forest no longer standing. These flowers reference the roble amarillo, a tree native to the Caribbean which is threatened by resource extraction and climate change. Animated by real-time trade wind data from the Caribbean region, the blossoms hover in a moment severed from time and space, their trembling reflecting a seeming disconnect from local history that is nonetheless viscerally felt. The ghostly floral canopy transformed histories of extraction and displacement into tangible, immediate experience, creating a haunting spatial narrative overhead. This attempt to mobilize perception permeated the biennale. Meanwhile, placed right across from this installation, Rirkrit Tiravanija’s large-scale text banner declared, “THE FORM OF THE FLOWER IS UNKNOWN TO THE SEED,” a phrase that resonated with the blooms as well as the event’s broader theme. On the second floor, Haegue Yang’s monumental Venetian blinds, Accommodating the Epic Dispersion – On Non-cathartic Volume of Dispersion (2012), shift between opacity and translucence, their suspended, adjustable forms evoking conditions of transition and impermanence.

One distinctive feature of this biennale was its non-hierarchical exhibition design, which allowed for an open spatial relationship between the artworks. Thai architect Rachaporn Choochuey, who oversaw the display layout, noted that she eschewed thematic zones in favor of open-ended drift: without clear narrative pointers to guide movement through the space, viewers were encouraged to instinctually navigate their surroundings by following sounds, light, or scents. This strategy, aiming to simulate nonhuman means of wayfinding, emphasized relying on intuition instead of prescribed intellectual guidelines. However, as most of the works demanded textual interpretation, the immediate viewing experience was often imbued with confusion, bewilderment, and disorientation. Whether intentional or not, this vertigo surprisingly mirrored the contemporary conditions of chaos, conflict, and anxiety caused by information overload and geopolitical turbulence.

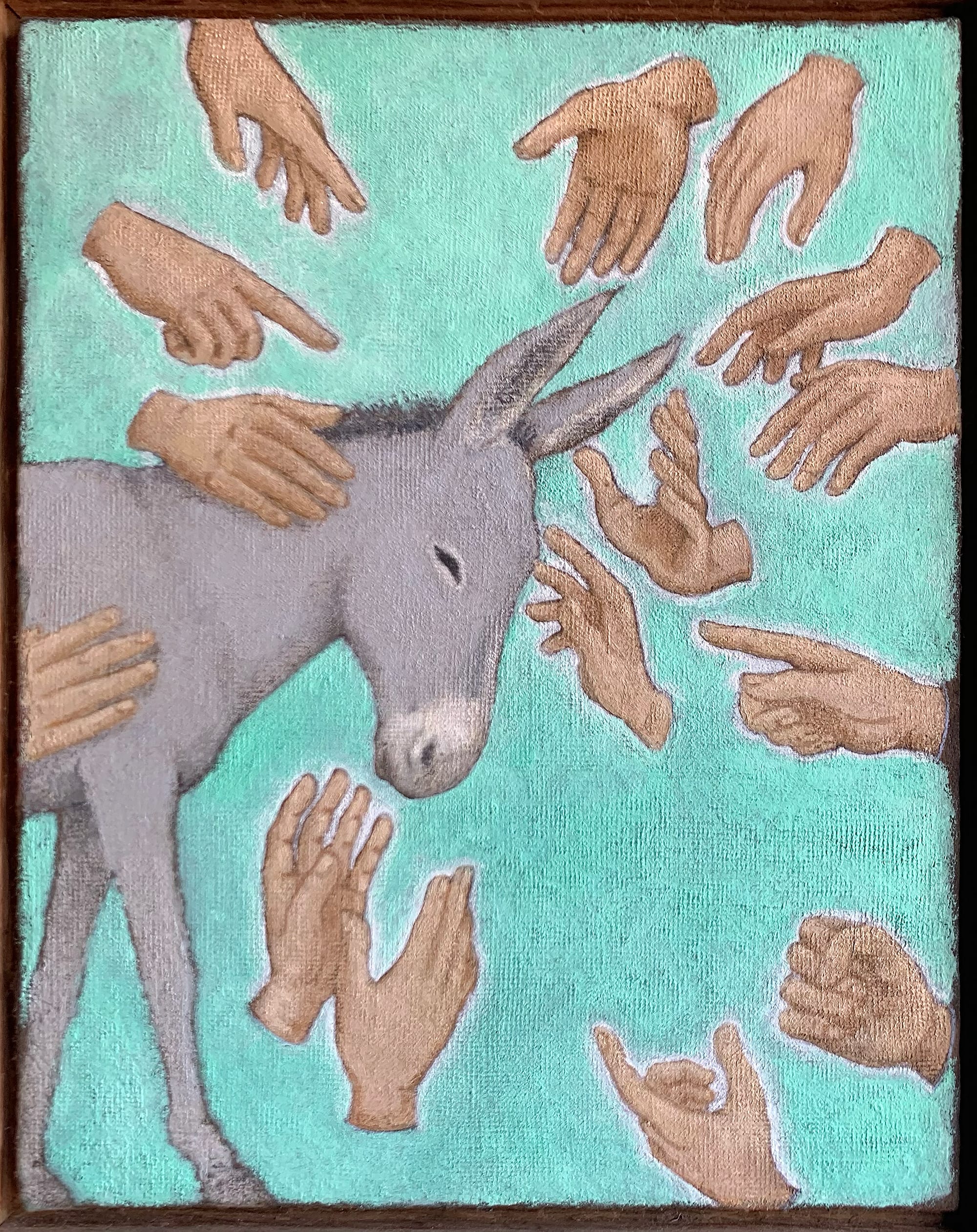

FRANCIS ALŸS, Children’s Game #30: Imbu, Tabacongo, DR Congo, 2021, video: 4 min 58 sec (left); and Untitled (detail), 2018–25, poliptych, two paintings, oil on canvas, 27.3 × 22.3 cm framed, 25.4 × 20.2 cm unframed; gold leaf on canvas, 25 × 18.8 cm; ephemera: pencil and oil paint on vellum, photograph, post-its, max. 24.3 × 26.5 cm (right). Courtesy the artist.

Drawn by the echoing of children’s laughter throughout PSA’s corridors, viewers came upon a darkened screening room showing videos from Francis Alÿs’s Children’s Games series (1999– ), which documents Mexican boys wielding flaming hockey pucks, and Danish children balancing fruit between each other’s foreheads. The cacophony of singing, humming, and whistling reverberated throughout the gallery. Against the bleak backdrops of war, conflict, violence, and poverty shown in some of the footage, these scenes of innocent childhood frolics present something approaching ritual or magic—a way of being in the world that perhaps resists the imposition of social structures and national boundaries. These 50-odd films from the series were shot over the course of two-plus decades during breaks from the artist’s exhibitions or commissioned projects, denoting a method that, one could say, enacts the kind of playful contingency depicted in the work itself.

The installation setup reinforced this conceptual framework. The screens were scattered throughout the darkened gallery, which generated a spatial dynamic akin to that of a playground. Children from different parts of the world appeared to play in spatiotemporal proximity to each other, as if they were participating in a simultaneous global game that transcended the geopolitical fractures dividing their actual lived realities. In an adjacent room flooded with bright light, new works from Alÿs’s Untitled series (1988– ) presented what he calls dream collages—hybrid works that combine oil painting with photography, embroidery, and found items to create enigmatic narrative fragments. Oneiric scenes projected onto the walls feature figures moving through pastel landscapes, hands making ambiguous gestures, and the recurring phrase “collapse of order.” One canvas in particular anchored the installation: a donkey set against a monochrome turquoise background, surrounded by a multitude of disembodied hands that seem to stroke, point toward, and gesture at the animal in ways that feel inscrutable. For viewers moving between the darkened room and this warmly lit space, Alÿs constructed a cognitive toggle between the social world and the psychic interior, seemingly suggesting that play operates as a hinge between these domains, a capacity to suspend normative consciousness and inhabit alternative temporalities.

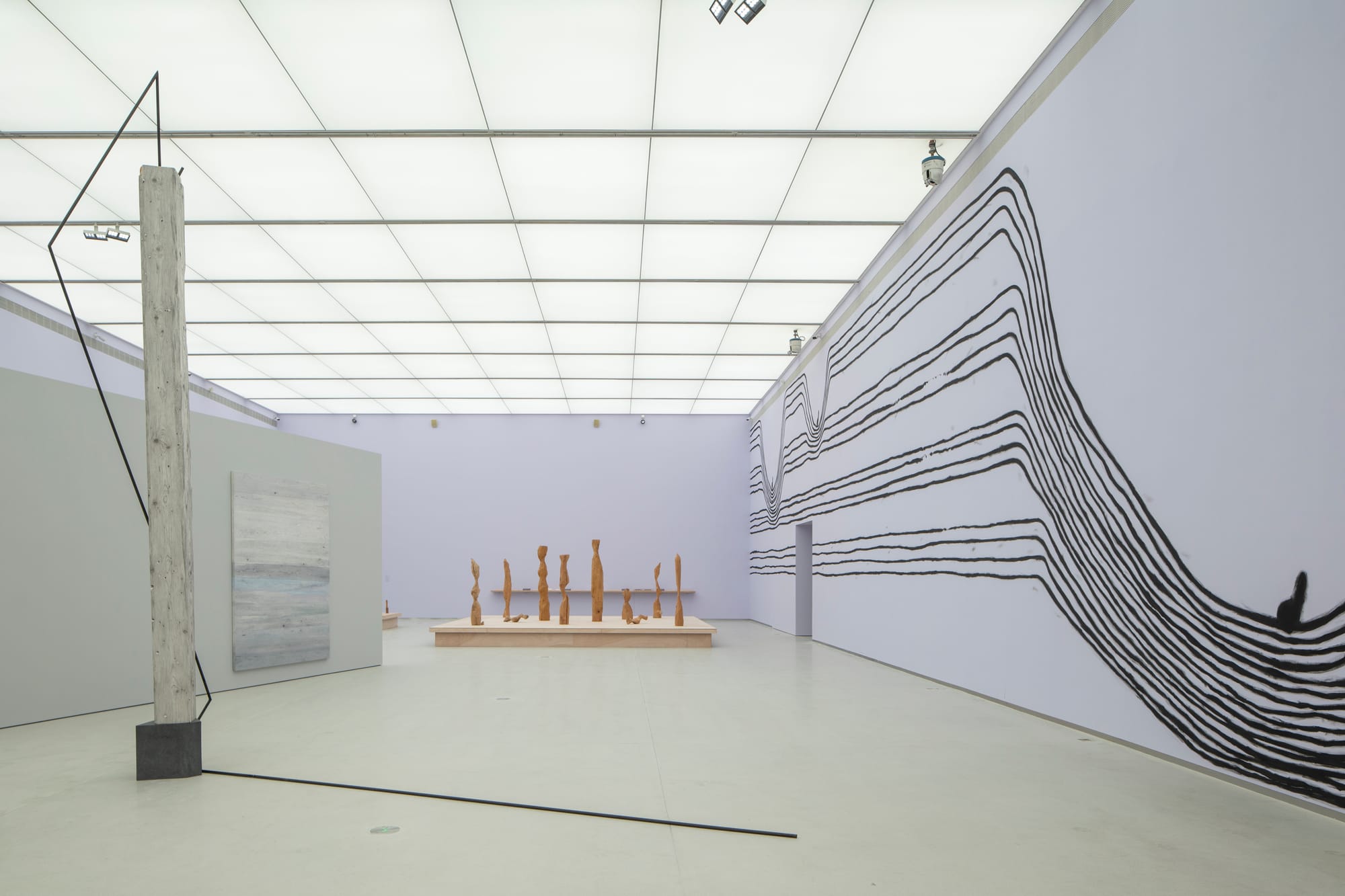

On the museum’s third floor, Christine Sun Kim’s Heavy Relevance (2024) translated the multiple gestures that exist in American Sign Language for the concept of “relevance” into large-scale musical notations, which spanned an entire gallery wall. The staff lines maintained their structural integrity at first, but as the eye moved across the composition, they began to sag and buckle under the weight of isolated quarter notes, creating a visual score that seemed to register social pressure and psychological burden. Kim deployed the symbolic system of hearing culture—musical notation, which presumes sound as its object—to foreground the fundamentally different processes of meaning-making that are specific to Deaf culture. There was an irony sharpened by the work’s extensive scale, which privileged vision as the primary mode of apprehension. Across the gallery, Cristina Flores Pescorán’s Abrazar el sol (Embrace the Sun) (2023–24) suspended native Peruvian cotton threads dyed with purple corn and copper rods in an intricate web-like formation that weaved together Indigenous knowledge systems, nutritional politics, and embodied memory. Refusing the Western separation between nature and culture, the work treats agricultural practice and cosmic understanding as intimately entangled forms of knowing.

Located in the same room was Aki Inomata’s How to Carve a Sculpture (2018–), a series of slender wooden forms that had been gnawed by beavers from Japanese zoos, then 3D-scanned and printed at human scale. The work challenges the conventional notion of authorship: is the sculptor the beaver, the artist who selected and presented the object, or the machine that reproduced it? Nearby, Hu Xiaoyuan’s multimedia installation I Am Rooted, But I Flow (2024) features a complex assemblage juxtaposing biological remnants like conches, insect wings, and coprolite with handwritten manuscripts and fragments of poetry, deliberately collapsing the distinction between natural residue and cultural production.

Other works in the exhibition pursued the curatorial premise of nonhuman communication on a more abstract and meditative level. Amar Kanwar’s The Peacock’s Graveyard (2023) layers poetic footage of flora and fauna with allegorical texts from South Asian folklore and oral history traditions. Presenting the material across seven screens, the installation conjured a kind of metaphysical space where human storytelling, beauty, life, and death become inextricable from one another. Rohini Devasher’s One Hundred Thousand Suns (2023), an equally ambitious multichannel installation, drew on the extraordinary archive of the Kodaikanal Solar Observatory in southern India, which has amassed more than 157,000 photographic images of the sun over the past 120 years. Here, Devasher interwove historical glass plate negatives, hand-drawn reproductions of sunspot patterns, solar data from NASA, and interviews with eclipse chasers. Without providing any narrative framework, the work asks viewers to shuttle between conflicting displays and incompatible scales of information, creating a condition of sensory overload that rejects any possibility of coherent comprehension. In our information-saturated age, the piece puts forth a proposition that even vast quantities of data collected with scientific rigor do not automatically produce knowledge.

Shao Chun’s Twinland (2025) extended the investigations of sensing, knowing, and desiring into an explicitly digital realm. Two soft sculptures hung from the ceiling, formed from masses of tangled threads that seem to reference both neural network diagrams and jellyfish anatomy, neither clearly organic nor mechanical. Micromotors embedded within these textile configurations generated subtle pulsations and tremors, evoking the unsettling impression of autonomous life. Moreover, ambient whispers filled the gallery space as video projections on the floor showed close-up footage of hands kneading, stroking, and manipulating amorphous various tactile materials—such as slime, furballs, and small stones—all sourced from ASMR content on the internet, where people seek out particular sensory triggers for their relaxing or pleasurable effects. The installation dispersed attention across textile objects, moving images, and immersive sound, refusing to establish any clear visual or conceptual hierarchy among these elements. Within this diffuse constellation of tactility, optics, and audio, desire circulated promiscuously without settling on any particular object. Twinland explores what could be called the contemporary libidinal economy, mapping something essential about intimacy and longing in cyberspace.

The biennale’s critical ambition was legible: it sought to challenge the anthropocentric regimes and extractive thinking that have brought about our current planetary crisis, just as the 2024 Venice Biennale mobilized the concept of “foreignness” to denaturalize assumptions about Western cultural centrality. Yet certain questions lingered, or even intensified. The night after the opening, I returned to PSA for Ragnar Kjartansson’s musical performance of Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe, A Poet’s Love (1840), which was staged directly beneath Allora & Calzadilla’s dangling forest. Watching the performance, I became enthralled, almost overwhelmed, by the melancholic song cycle of Schumann, the beauty of the yellow artificial petals drifting slowly, and the grandeur of the atrium. I could not help but wonder: can we genuinely grasp the ecological violence in the Caribbean, or does it become merely abstracted into an aesthetic encounter? When experiences tethered to specific traumas and histories travel across such radically different cultural zones, what actually arrives? What meanings get lost in this translation, and what new ones emerge that the artists never intended? The biennale urged us to listen beyond the human, to attend to alternative epistemologies. Yet the more difficult inquiry might be how such knowledge systems can truly take root in contexts far from their origins, and how they might become not just topics of curatorial interest but actual methods for understanding the world we inhabit.

Louis Lu is an associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.