Shows

Kazuko Miyamoto and Lydia Okumura “Minimalist Anyway”

Kazuko Miyamoto and Lydia Okumura moved to New York in 1964 and 1974 respectively, the former from Tokyo and the latter from São Paulo. There, they each developed a sophisticated practice confronting the Minimalism that had predominated in the 1960s and early 1970s. Despite their similarities, the two had only exhibited together once, in 1980, prior to “Minimalist Anyway” at London’s White Rainbow gallery. This was a rare opportunity to witness a dialogue between two independent contemporaries working at the forefront of an exciting and challenging juncture in recent art history.

The exhibition’s point of departure was a comment Miyamoto made during a conversation with artist and gallerist Christian Siekmeier in 2012: “Being Japanese you are minimalist anyway.” Concerning a broad, aesthetically focused conception of Minimalism, this may be true. However, in the white male-dominated context amid which Miyamoto and Okumura operated during the 1970s, the artists’ willingness to acknowledge backgrounds, bodies and politics set them apart from their predecessors. This imbues their work with a charged, often ironic commentary that questions Minimalism, and the homogeneity of its best-known practitioners.

Both artists displayed pieces whose titles subtly subvert minimalist principles. Miyamoto’s knee-high, black-and-white-striped sculpture in the shape of a hash-symbol, Well (1973), disregards a central premise of Minimalism by bearing a name that supports a figurative interpretation, inviting the viewer to peer into its central space and to consider a real-life referent, beyond the sculpture. The piece resembles works by Sol LeWitt, to whom Miyamoto was a close friend and one-time assistant. However, its title challenges the candidness with which LeWitt might have named a similar work according to Frank Stella’s maxim: “What you see is what you see.”

While also subtly referencing the external, Miyamoto’s Male I (1974) is named more ironically. Constructed from many threads of black string, nailed in a one-to-many configuration between the wall and a wooden board on the floor, it questions not only the tenets of minimalist art, but also its production. The piece’s impermanent materials contradict the minimalist attraction to industrial processes and forms, while the installation’s resemblance to a loom recalls hands-on labor techniques traditionally associated with women. Male I is also remarkable for its optical effect, where crossing black strands merged and juddered as the viewer moved across the space. This drew attention to the visitor’s body in relation to the installation, defying the minimalist call for purely self-referential art.

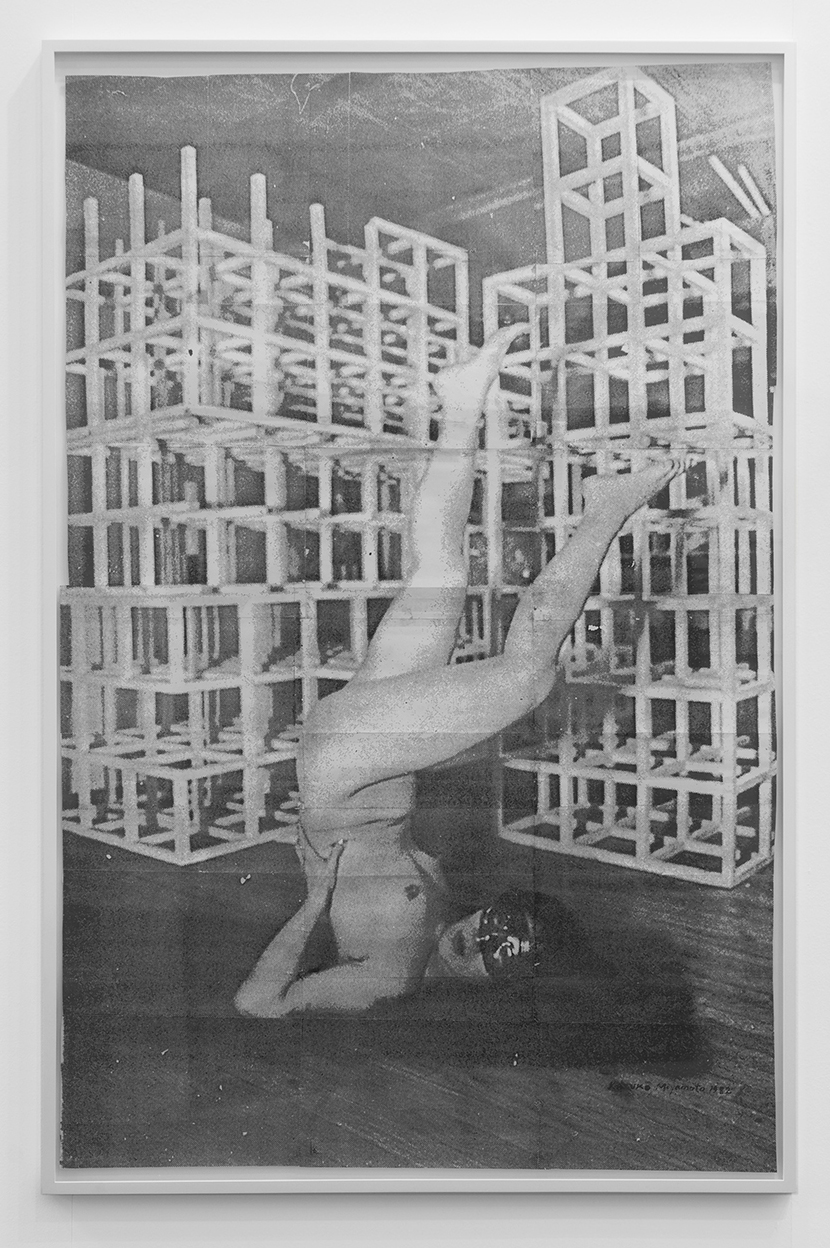

In another work by Miyamoto, the relationship between the body and minimalist form is further explored. Stunt (181 Chrystie Street, 1981) (1982) is a large photocopy piece comprising roughly 44 prints, showing the naked artist engaged in a shoulder stand before one of Sol LeWitt’s “open cube” sculptures. The artist’s naked body, the juxtaposition of the organic and industrial, the unique rendering of the image and even the defiance extended through the artist’s direct gaze toward the camera—which recalls the gaze in Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863)—are all at odds with minimalist dogma and challenge its male domination.

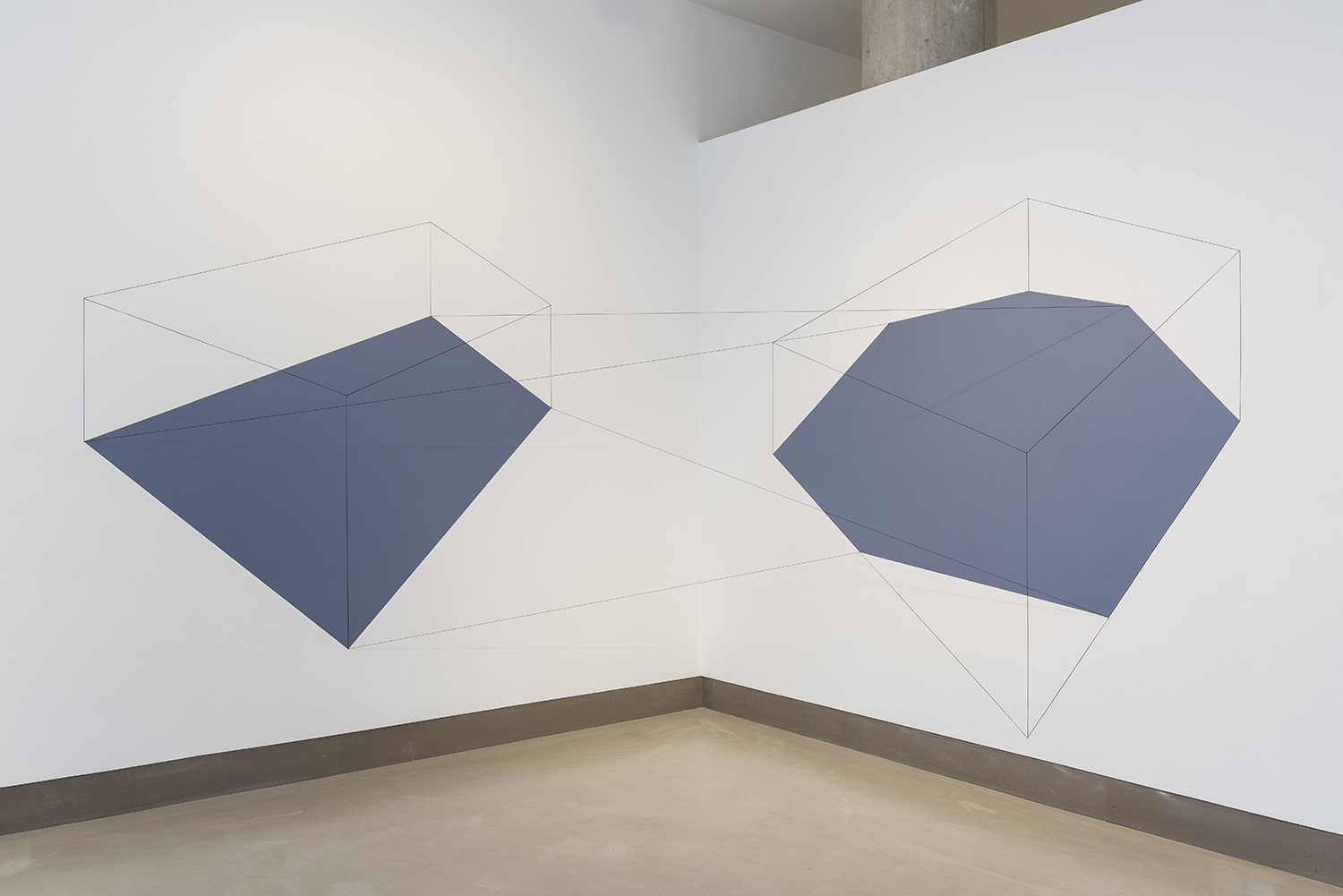

Okumura’s work also creates an awareness of the existence of the body, reflecting the neo-concretist tradition of Brazil where she was born. In Untitled I (1980), two linear axonometric projections containing shaded planes are drawn on perpendicular walls and connected at various nodes by lengths of string. A counterintuitive geometry of lines, planes and volumes—existing both on the walls and between them—alerts the viewer to the illusory nature of the projections, reminding them of their own physical presence in the gallery space.

Many minimalists denounced illusion, in particular its depth in two-dimensional works. However, both artists displayed pieces where pictorial space recedes from the picture plane. Okumura’s “Diagram of the Reason” series consists of three framed images depicting forms similar to those in Untitled 1. In the same vein, Miyamoto’s Box (1975) features an archetypically minimalist box form drawn in cartoonish lines that reveal the artist’s hand, and is an irreverent nod toward the genre’s rigorous rulings.

Taken at face value, Miyamoto’s off-hand comment is disputable, even reductive. However, through the works here, it becomes a call-to-action: a way of claiming ownership of the term “minimalist” while expanding beyond the constraints imposed on it by a dominant group.

Kazuko Miyamoto and Lydia Okumura’s “Minimalist Anyway,” curated by Edward Ball, is on view at White Rainbow, London, until June 10, 2017.