Shows

Ho Sin Tung’s “Surfaced”

Ho Sin Tung shares her love for classic cinema in “Surfaced” at Chambers Fine Art. “She is a huge, huge film buff,” the gallery’s director Daniel Chen said of the young, but already well-established Hong Kong artist who is showing in New York for the first time. Following the success of her exhibition at the gallery’s Beijing space, Chen opted for a more pared down version at its Chelsea location, which features the same series, as well as some newer works.

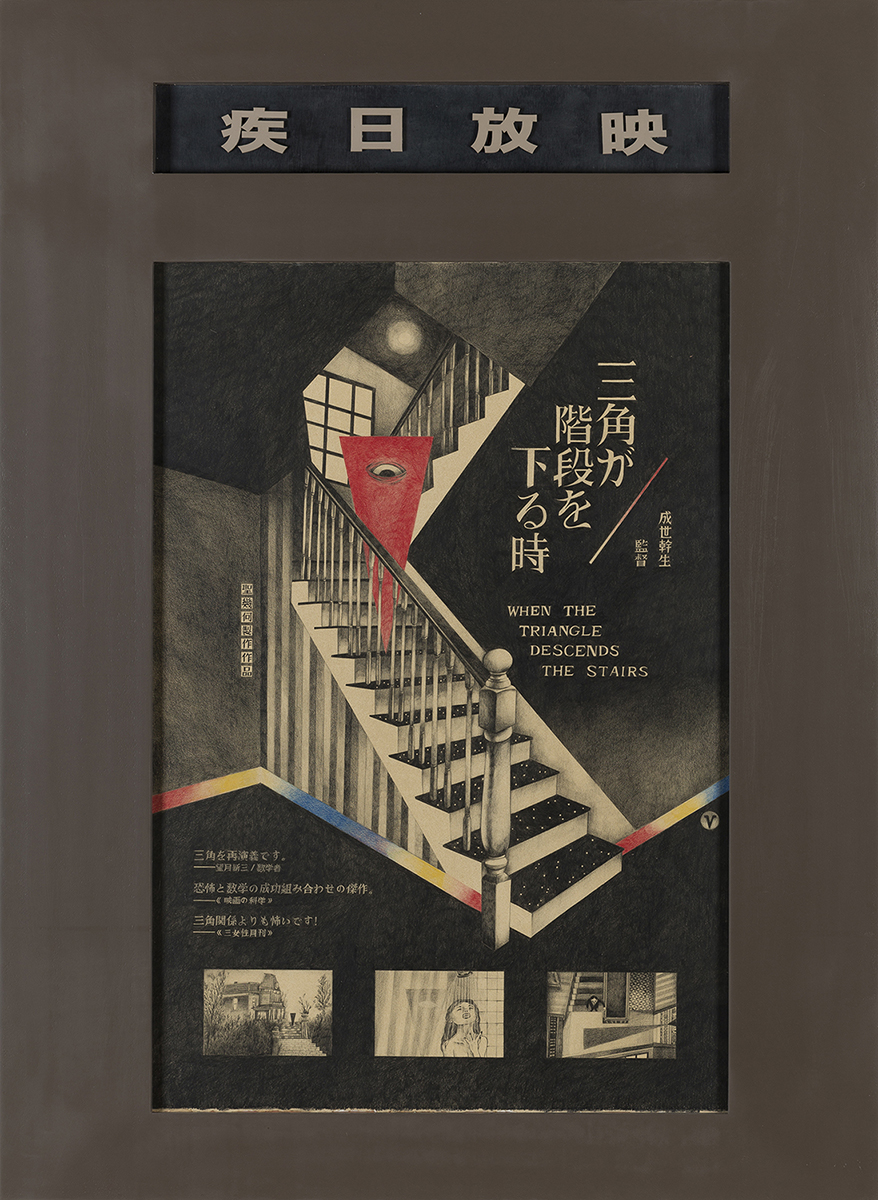

Aficionados of Old Hollywood will recognize many of the references in Ho’s posters for fictitious horror films. In real life, the desire to face her fear of scary movies fueled her deep dive into all genres of horror—from Hitchcock to B-movies to Japanese horror. With a nod to Psycho’s famous shower scene, When the Triangle Descends the Stairs (2016) turns the cinematic trope of “the reveal” on its head by immediately giving away the monster in the poster. The absurdity of a one-eyed geometric shape as an object of dread also raises existential questions about the nature of fear.

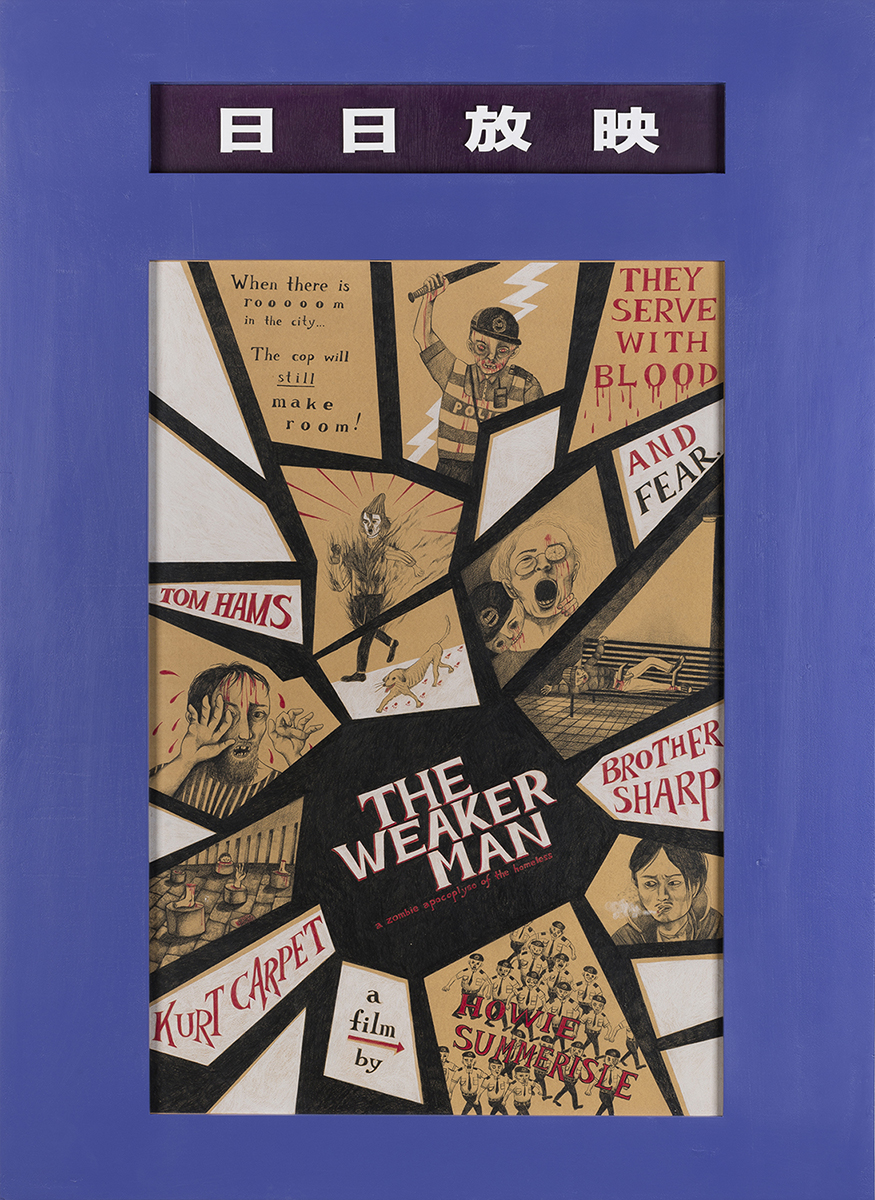

Drawn entirely in color pencil, the works highlight not only Ho’s technical skill but also her attention to detail. Everything has been meticulously conceived, from the copy in the poster’s fine print to their frames mimicking those found in theater lobbies. Again, she uses every opportunity to create layered meanings. For example, if spoken aloud, the words 疾日放映 (jírì fàngyìng), seen in the header of the poster, sound like “released today” or “now showing,” but the first character actually translates to “disease,” suggesting that a kind of sickness has been released, instead.

In The Weaker Man (2016), a play on the 1973 thriller The Wicker Man, the pun serves as a political statement. Ho illustrates policemen transformed into a hoard of mindless zombies, and the homeless as their victims, in order to critique police brutality and the mistreatment of Hong Kong’s most vulnerable population. Meanwhile in Frankensticker (2016), the female figure covered in pictures of body parts is herself the abomination, created out of society’s need to control women and impose unrealistic standards of beauty upon them.

Addressing a theme common in science fiction where the natural world turns against humans, Outlive the Light (2016) features illustrations of the sun becoming so hot that people begin to melt. These imagined film stills hang in cabinets designed by Ho to replicate the classic boxes for previewing theatrical releases that she used to see around Hong Kong. Ho created other ephemera with vintage appeal including newspaper advertisements for films spoofing the art world and LP covers—both of which are brand new works that are being shown for the first time. Chen joked that the gallery ended up looking like a “thrift shop.”

In another corner of the room, what appears to be a small library, complete with a desk and wall-mounted shelves, displays book covers that Ho painted to replicate all 17 existing editions of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899). Stripped of all text, Heart(s) of Darkness(es) (2016) investigates how the original artists attempted to encapsulate the story’s literal and psychological journey on one small surface. Ultimately, the reader discovers that “The horror! The horror!”—as proclaimed in the novel’s iconic line—stems from within civilization itself.

This illumination of humanity’s dark side culminates with Last Party (2016), a one-room installation that pays homage to Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), directed by Italian filmmaker and writer Pier Paolo Pasolini. Set during the Fascist occupation of the 1940s, the notoriously hard-to-watch film subjects its characters, who are depicted in portraits hanging on the walls, to sadistic torture and sexual violence. While Ho’s work does not explicitly show any of these acts, the geometric design of the carpet, copied from the one used in the film, alludes to where they physically take place. On screen, Pasolini’s poem “Goodbye and Best Wishes” rolls like credits, while Ennio Morricone’s haunting theme plays on loop.

Through the telling and retelling of various horror narratives, it becomes clear that what has “surfaced” are not alien forces but rather manifestations of our internalized anxieties. For Ho, what began as an exercise to confront her personal fear effectively concludes as an examination into our own monstrosity and collective capacity for evil.

Ho Sin Tung's "Surfaced" is now on view at Chambers Fine Art, New York, until April 1, 2017.