Shows

Chow and Lin’s “Even If It Looks Like Grass” at Bounded Space, Beijing

Chow and Lin

Even If It Looks Like Grass

Bounded Space

Beijing

Sep 4–Oct 8, 2025

When I stepped into Chow and Lin’s exhibition “Even If It Looks Like Grass” at Bounded Space, Huiyi Lin handed me a tiny binocular telescope—an unusual gesture that suited the ambitious installation well. Created between 2023 and 2025, the titular work centers on 11 large-scale aerial photographs of major wheat-producing regions and the architecture of data centers. Each is divided into grids, fragmenting the presumed seamlessness of satellite imagery, which in fact results from multiple instruments capturing data across different times. Around them, more than 4,000 sheets of paper covered three walls from floor to ceiling, charting the artists’ research process. Many were illegible from afar, forcing me to zoom in and out to decipher faint details or guess at fragments tucked high in the corners.

This shifting of scale became the exhibition’s first lesson, and it is also a key to understanding the duo’s methodology. Working together since 2009, photographer Stefen Chow and economist Huiyi Lin have developed a practice merging sociological research with visual form, and probing how global structures—poverty, food systems, data economies—materialize in the fabric of everyday life.

Initially commissioned by the Lahore Biennale in 2024, Even If It Looks Like Grass stages a history of wheat cultivation stretching back over 10,000 years, juxtaposed with its contemporary equivalent: the vast architectures of data centers. Agriculture and information technology are presented as parallel revolutions in human history—infrastructures that enable survival, concentration of power, and global exchange.

Many of the materials on display reconfigured the conventional notion of archive. Chow and Lin assemble a constellation of academic studies alongside brand promotions, pasta recipes, readymade food slogans for social media, screenshots of TV dramas in which characters eat steamed buns, and snapshots of wheat products available on a given day from a Chinese e-commerce platform. The “archive” acquires a humane texture, probing how wheat and data intersect with daily consumption, technological operations, global economies, ecological systems, and ethical frameworks. At one extreme of materialization, a stone grain grinder sat in the center of the gallery, inviting visitors to hand-grind wheat berries: a bodily enactment of subsistence transformed into sustenance.

The artists’ working method fuses their respective backgrounds—Lin in economics, Chow in photography. Their long-term project The Poverty Line (2010– ) remains the clearest expression of the approach that borrows from economic sociology while insisting on visual form. Traveling across 38 countries, the duo calculated the amount of food that could be purchased on a daily poverty income, and photographed the results against local newspapers. In this exhibition, a small selection of images from the series featured wheat products from six cities—Beijing, New York, Rio de Janeiro, Addis Ababa, Paris, and Sydney. Here, a sociological metric is translated into a stark, serial image: at once statistical comparison and visceral display. Chow and Lin’s methodology shifts between structural perspectives, from global food systems and comparative data to intimate registers, such as the rituals of eating and the minutiae of daily life, making abstract numbers legible as lived experience.

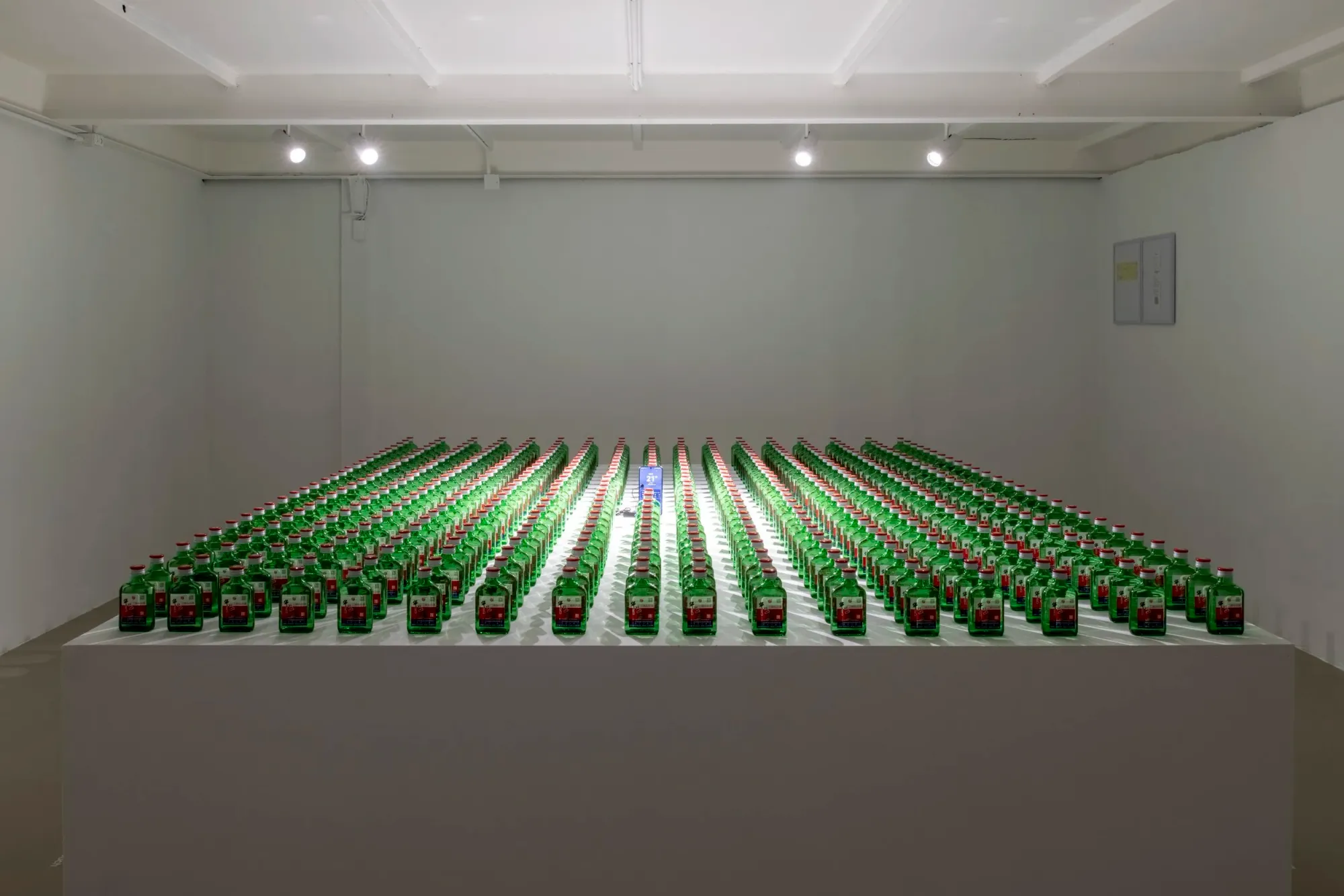

This logic also underpinned Decentralized Value Systems (2025), where a Huawei smartphone sat surrounded by 456 bottles of Erguotou—a liquor originating from and produced in Beijing, made largely from wheat. The arrangement created a near-sacred tableau: the emblem of Chinese contemporary technology encircled, even worshipped, by its agricultural counterpart which once drove a craze in the Chinese stock market. Quotes displayed on the wall reveal that the two products were acquired at the same price—worth here is visualized as mere equivalence, exposing the absurd omnipresence of price as determinant. If wheat and data are infrastructures of survival, liquor and consumer electronics are commodities of desire, tethered to the same economic circuitry.

The setting of Beijing adds another inflection to the works. In 2022, the capital recorded the lowest Engel’s coefficient in the country, with food expenditure becoming a negligible part of household income. While scarcity may not be a daily concern for most of its residents, Chow and Lin foreground the fragile infrastructures of eating, feeding, and being fed, where local abundance coexists with global precarity.

Against this backdrop, the exhibition’s opening work, The Conversation–Dailies (2021–25), might at first seem out of step with the themes of poverty and political economy: a conversation recorded daily between the artists, projected to continue until 2061, when they will near the statistical limits of life expectancy in their home countries. It extends the duo’s methodological frame to the most intimate scale, as each video captures the passing trivialities of daily life, including the vulnerable period after Lin’s cancer diagnosis. Here, lifespan is imagined as an aggregate measure, while each utterance remains fleeting.

The exhibition concluded with Everything I Own (2025), which suffused the entire gallery. In the multimedia installation, the industrial scent of bread designed to trigger appetite drifted through the space, mingling with audio recordings of the artists cutting, tearing, and eating it. Domestic familiarity collided with mechanical replication: sustenance became signal, intimacy became broadcast. Wheat’s history as currency, staple, and symbol contracted into this unnerving sensorial field, leaving the audience caught between bodily fact and systemic abstraction.

Shanyu Zhong is a Beijing-based writer, editor, and translator.