Shows

“Border(line)” at David Zwirner, Hong Kong

Border(line)

David Zwirner

Hong Kong

Sep 13–Oct 25

The word “border” inherently carries a dual meaning: it suggests both division—the line that separates—and paradoxically, a zone of contact where different territories meet. In our current era of geopolitical upheaval, with conflicts raging from Ukraine to Gaza, the concept of borders has become increasingly fraught, invariably laden with implications of biopolitical control. Today, borders are both cartographic lines delineating national boundaries and state mechanisms that fundamentally regulate human existence. The group exhibition “Border(line)” at David Zwirner Hong Kong explored this contested domain, featuring works that probe how artists navigate the physical and psychological boundaries that shape lived experience.

Belgian artist Francis Alÿs’s Painting/Retoque (2008), which anchored the exhibition, offered perhaps the most direct exploration of political borders. In the video, Alÿs documents himself repainting the faded lane markings on a road crossing the Panama Canal. There is a ritualistic solemnity in this seemingly simple, repetitive gesture that draws viewers in. This oblique approach to geopolitics has been a hallmark of Alÿs’s practice since the 1990s, when he undertook a series of actions that could be termed “poetic futility”: pushing a block of ice through the streets of Mexico City until it melted completely, or walking along Jerusalem’s Green Line with a leaking can of paint. Through these quixotic interventions, Alÿs raises challenging questions about the arbitrariness of political boundaries, and how these flexible constructs—shaped by geographical or historical contingencies—wield overwhelming influence over economic, social, and ideological realities.

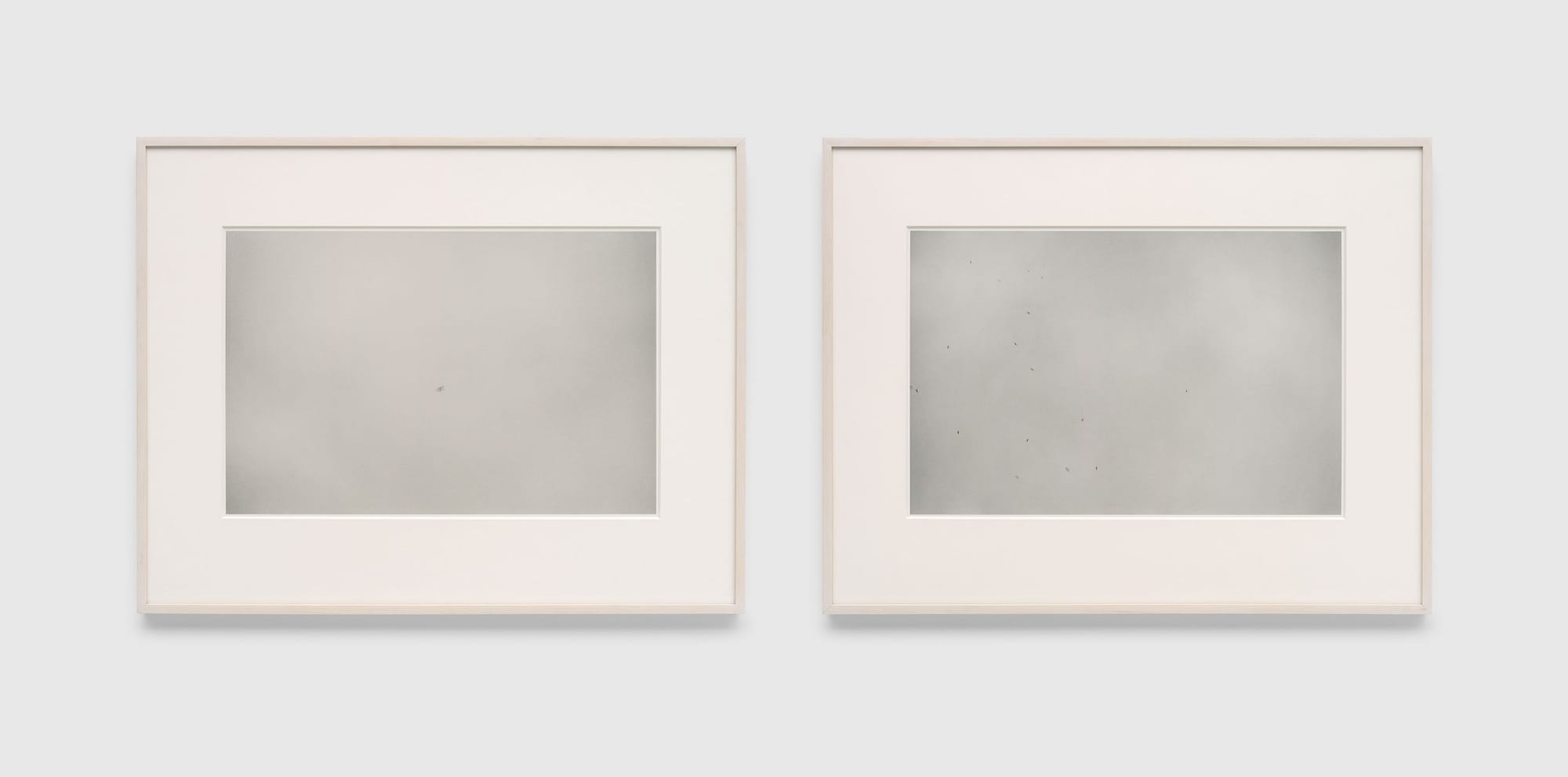

Félix González-Torres’s “Untitled” (Diptych) (1994), in contrast, is less a direct confrontation with physical infrastructure than a metaphorical meditation on migration and belonging. The photographic diptych comprises two images of birds, both against bleached skies: the left features a solitary avian, while the right captures a scattering flock dissolving into atmospheric gray. These birds, moving across national borders according to seasonal patterns that predate human politics, seem to articulate González-Torres’s yearning for community and an abstract notion of “freedom.” They reflect a cosmopolitan ideal of movement, intertwined with the melancholy of displacement and the perpetual foreignness that defines the migrant condition.

Beyond geopolitical landscapes, we navigate interior geographies of familial bonds and cultural and personal memories. Chinese artist Hu Xiaoyuan’s sculpture Carpel III (2025) turns inward, examining the boundaries between permanence and dissolution. Named after the female reproductive organ of flowering plants, the work presents a rosewood branch emerging from carved marble, gradually transforming into a delicate tubular mesh. Crafted from xiao (raw silk), one of the artist’s signature materials, this diaphanous extension supports another xiao structure—the ghostly double of the marble base below. The sculpture’s fragile state evokes the liminal threshold in which matter migrates between different states of being.

Adjacent to Carpel III was a painting by the same artist, titled Wood / Time Branch VI (2025), that expands on her investigation of surface and substrate. Inspired by her observations of volcanic crater lakes, the work ostensibly presents colors of turquoise and blues that suggest placid waters. However, the tension between the serene surface and the potential of volcanic eruption is expressed through her elaborate process: Hu began by covering wood panels with translucent xiao, then meticulously traced the wood grain onto the fabric surface. Next, she applied paint to the panels, masking their original texture, before transferring the grain patterns preserved on the xiao back onto the painted surface. This process of tracing and re-inscribing creates a visual deception in which the original wood grain and its painted reproduction become indistinguishable, indirectly echoing the duality of the xiao itself: its delicate texture might evoke feminine fragility, yet the production of raw silk inherently involves violence—silkworms are boiled alive, their cocoons unwinding under pressure into fine threads.

In his book Imagined Communities (1983), Irish historian Benedict Anderson argued that print media fostered a shared linguistic and cultural space through reading experiences that crystallized into national identities. This media ecosystem, according to Anderson, produced relatively stable conceptions of borders and belonging. Today, however, as digital feeds fragment communal narratives and TikTok videos capture border crossings in real-time, these once-solid categories have become increasingly fluid and uncertain. We must ask: what becomes of collective identities and, more broadly, our faith in structures of belonging? As boundaries evolve—simultaneously fortified by surveillance towers yet often rendered invisible by viral videos—“Border(line)” offered a hopeful, if somewhat elusive, response: the apparent solidity of borders will continually be undermined by the very flows—of people, matter, and meaning—that they purport to contain.

Louis Lu is an associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.