Shows

Between and Beyond Language: The Rhythms of Colomboscope 2026

Colomboscope 2026

Rhythm Alliances

Colombo

Jan 21–31, 2026

Founded in 2013, Colomboscope is an interdisciplinary festival based in Sri Lanka, bringing together artistic practices from South Asia and beyond through exhibitions and performances staged across Colombo. Led by artistic director Natasha Ginwala with guest curator Hajra Haider Karrar, its ninth edition, “Rhythm Alliances,” approaches rhythm as a working premise rather than a prescriptive theme, opening onto questions of embodiment, transmission, and mediation. The scope of practices emerges early on, from Raven Chacon’s open-ended scores—shaped through reiteration, minimal sonic gesture, and Indigenous Diné traditions—to Chamindika Abeysinghe’s pixel-art video game Taala Village (2024–25), where traditional Sri Lankan instruments operate as navigational cues within a pixelated virtual environment.

“Rhythm Alliances” unfolds across five exhibition venues whose distinct histories actively inflect how the works are encountered. At Colpetty Town House, once a multigenerational residence and now repurposed as a three-story exhibition space, the curation remains closely attuned to the site’s domestic past. Literary practices, craft lineages, and digital works activate lived interiors rather than neutral display contexts, with natural light and street sounds permeating throughout, blurring boundaries between inside and outside, private memory and public life.

Several presentations engage with Sri Lankan traditions threatened by erasure and extraction: Aboothahir Al Wajahath reworks the handloom tradition through spindle forms that allude to industrial pressure; Imaad Majeed pairs machine-driven percussion with archival sound recordings that sustain marginalized Sufi soundscapes; and P. Ahilan’s picture poetry mobilizes Tamil literary traditions to position language as rhythmic memory.

Elsewhere in the venue, Basma Al-Sharif’s installation a Philistine (2019–23) assembles photographic prints from former Yugoslavia, reworked archival material from Egypt and Palestine, and a communal seating arrangement for reading a novella—written by the artist and available only on site. The narrative follows a woman’s journey through Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt in search of a father she never knew, forging an idiosyncratic pairing of contested geographies charged with a sensual pull that at once propels and destabilizes the trajectory, bending the journey sideways. A related sensibility informs Tashyana Handy and Sakina Aliakbar’s For Private View and Public Disappearance (2025), a meticulous reconstruction of a young woman’s bedroom that gathers voice recordings, personal ephemera, and literary references. A poem written on the window—“You, speak English bestest; You, middle class brightest; You, everywhere but your body”—crystallizes the contradictions of inhabiting a young female body in contemporary Sri Lanka. Taken together, these works resist thematic reduction by situating desire, gender, and class within acts of reading and dwelling, insisting on personhood constituted by precarity and postcolonial inheritance.

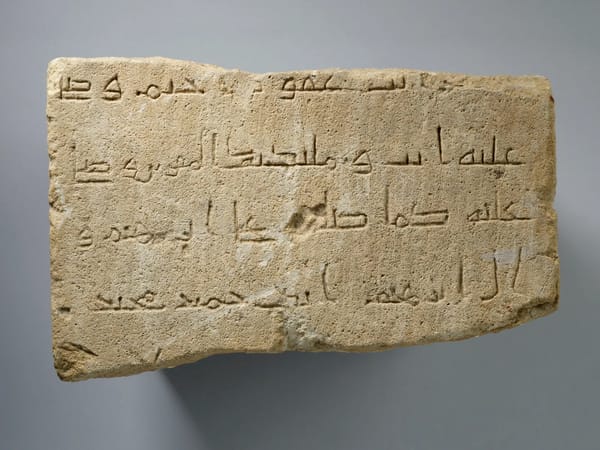

At Radicle Gallery, a former colonial-era commercial office building, the exhibition centers distilled forms and modes of communication that operate at the edge of language. Moe Satt’s sculptural hand gestures propose a nonverbal vocabulary of connection in contexts where the desire to communicate is met with antagonism and terror. In a related but spatial register, Naiza Khan undermines rigid cartographies of power through fluid architectural imaginaries rendered in watercolor and sound, advancing a counter-cartography that is mutable and leaking. Questions of absence and displacement surface in Seher Shah’s Woven Nights (2025), a series of concertina book of monotypes and shadow prints installed in undulating waves, where absence registers more sonorously than presence. This work accompanies her poetry volume Between a Home and a Horizon (2025)—translated into both Tamil and Sinhala—which traces ambivalent impressions of displacement and hope drawn from the artist’s decade in New Delhi.

Extending this turn toward abstraction under conditions of historical violence and linguistic failure, transnational solidarities come into focus in Nina Mangalanayagam, Marie Louise Dilmaya Bergqvist, and the Transnational Adoptee Choir: The Whale’s A Song from Across the Sea (2025). Drawing on research about Sweden’s colonial history and a whale calf killed in 1865, now preserved in a Swedish natural history museum, the project links colonial trade routes to the transnational adoption industry through the fragile act of humming. Performed collectively, humming bypasses linguistic boundaries to produce immediate co-presence, allowing sound to function as embodied attunement in which separation, loss, and dislocation are held in suspension. The choir’s address to the whale calf extends this gathering beyond the human, proposing reverberation as a response to absences that cannot be fully archived, spoken of, or repaired.

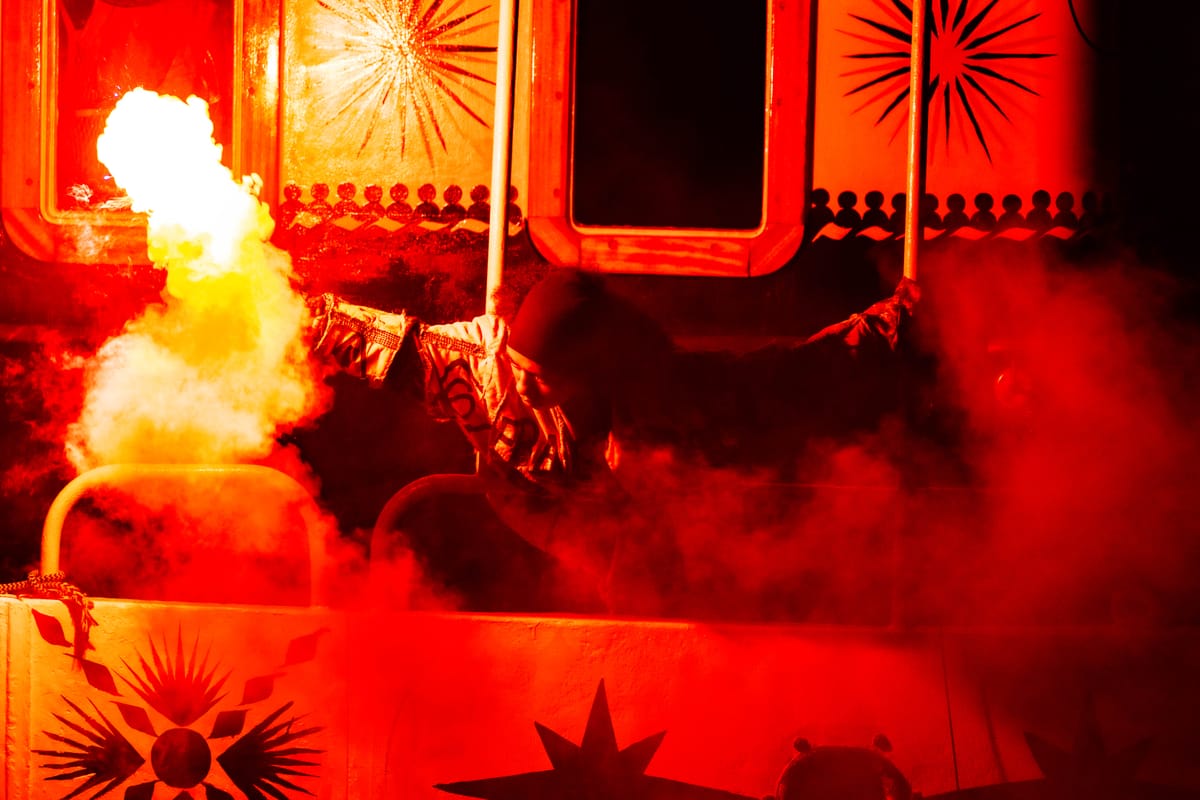

At the Rio Complex, the venue’s layered history confronts erasure through reenactment and disjointed performance. Once a site of midcentury cinematic optimism and later marked by the political violence of the 1980s, the cinema becomes a charged setting for Basir Mahmood’s A Body Bleeds More Than It Contains (2026). Developed with former workers from Pakistan’s declining Lollywood industry after the partial demolition of Bari Studios, the work is rooted in restricted access and irreversible loss. Unable to fully return to the site that used to be one of Pakistan’s oldest film studios, participants—both performers and audience—reenact fragments of memory through movement, song, and emotionally charged monologue. As chairs are dragged and bodies repositioned, a staged death and a mother’s lament recur, allowing memory to circulate. Rather than mourning disappearance, the work traces persistence, realigning performance, affect, and labor beyond the stabilizing logic of documentation: a shared presence in which lost fragments endure by entering an alternative mode of existence.

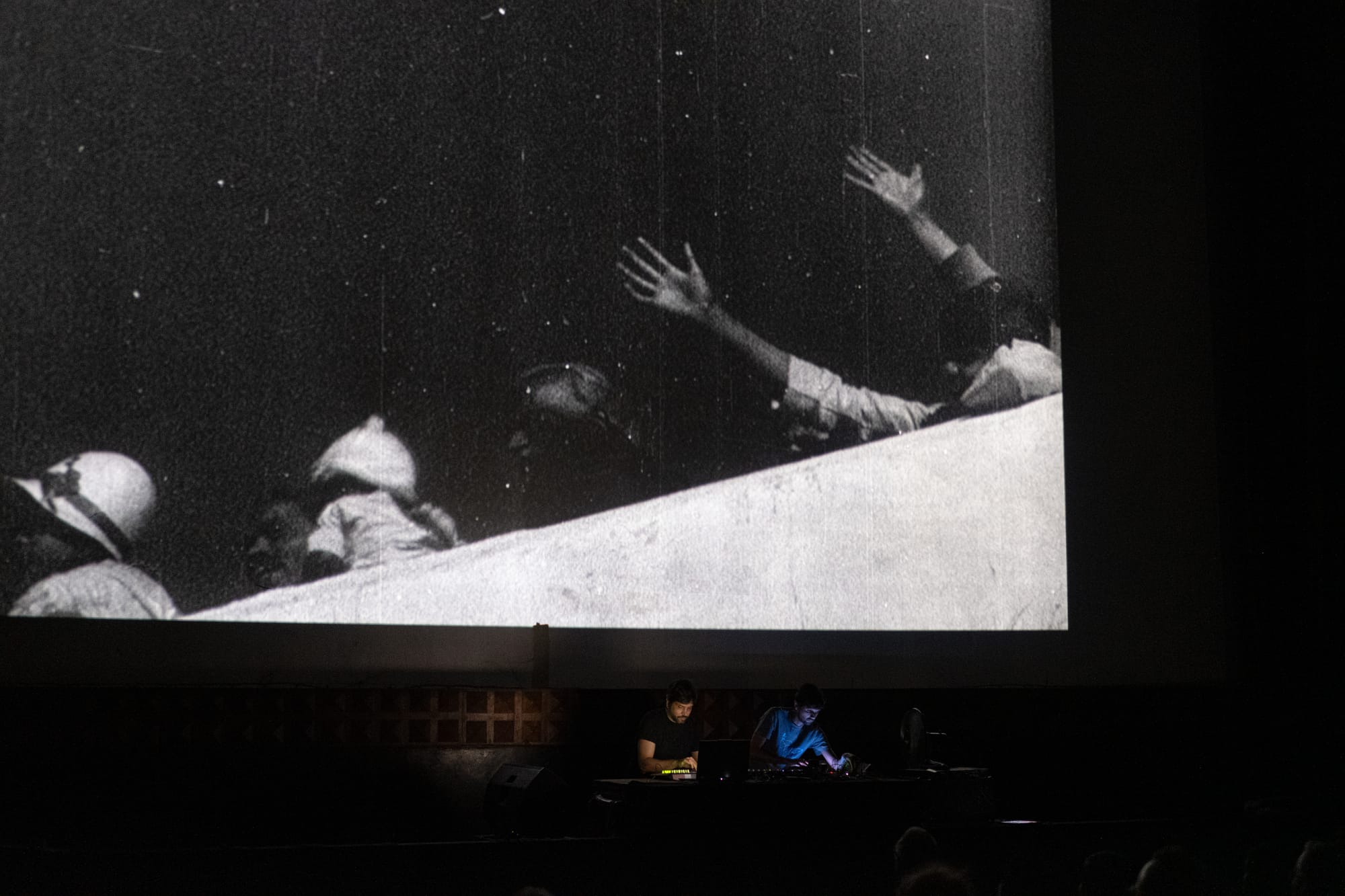

This collective rewriting of cinema culminates in a reworking of The Song of Ceylon (1934), originally directed by Basil Wright and supported by the Ceylon Tea Board. Accompanied by a contemporary electronic score by Asvajit Boyle and Nigel Perera, the screening displaces the original film’s triumphalist narration and orchestration into a faint murmur. Subdued beats reintroduce pulse and agency to bodies once exoticized and religious rites once idealized as ethnographic spectacle, rendering the colonial archive unstable, haunted, and unresolved.

Rhythm is articulated explicitly as a practice of alliance across time and region at Soul Studio, a sustainability-conscious meeting ground for local architects and creators. This ethos resonates in Ayumi Paul’s graphic scores, where constellations stitched in gold and white on organic paper evoke planetary timescales, inviting cyclical relations of listening and movement and treating cosmology as a shared rhythmic structure. A different genealogy of musical alliance appears in Atiyyah Khan’s research-driven work on As-Shams Records, a label founded in Cape Town and active during apartheid. Tracing familial migration from India and colonial routes shaped by indentured labor, Khan foregrounds jazz as a site of cross-racial and diasporic bonding, attesting to rhythm as a social adhesive forged under conditions of segregation and surveillance.

Finally, Arka Kinari stages one of the festival’s most striking gestures: a live music performance unfolding on a solar-powered sailing vessel at Colombo’s contested Port City. Carried by wind and tide, Filastine and Nova’s percussive and electronic compositions—inflected with traditional Javanese melodies—spill across the open shoreline as projection screens flap in the wind, refusing the fixity of a stage. Moving through waters reshaped by extractive development and ecological strain, the performance binds disparate territories into a shared acoustic field, calling listeners to attend, reckon, and align across fracture.

Across its dispersed sites, “Rhythm Alliances” approaches rhythm as a mode of articulation that moves between and beyond language. Through poetry, gesture, vibration, and reenactment, the works carry the reverberations of past and ongoing suffering. Situated in Colombo, a capital shaped by layered histories of violence, extraction, and contestation, the festival treats such density not as impediment but as medium, privileging shared moments of listening and encounter and allowing solidarity—uneven, provisional, and not necessarily in sync—to emerge through the collective labor of holding rhythm together.

Jiwon Yu is a curator, writer, and translator mainly based in Seoul.