People

Wavelengths of an Idea: Interview with Ayşe Erkmen

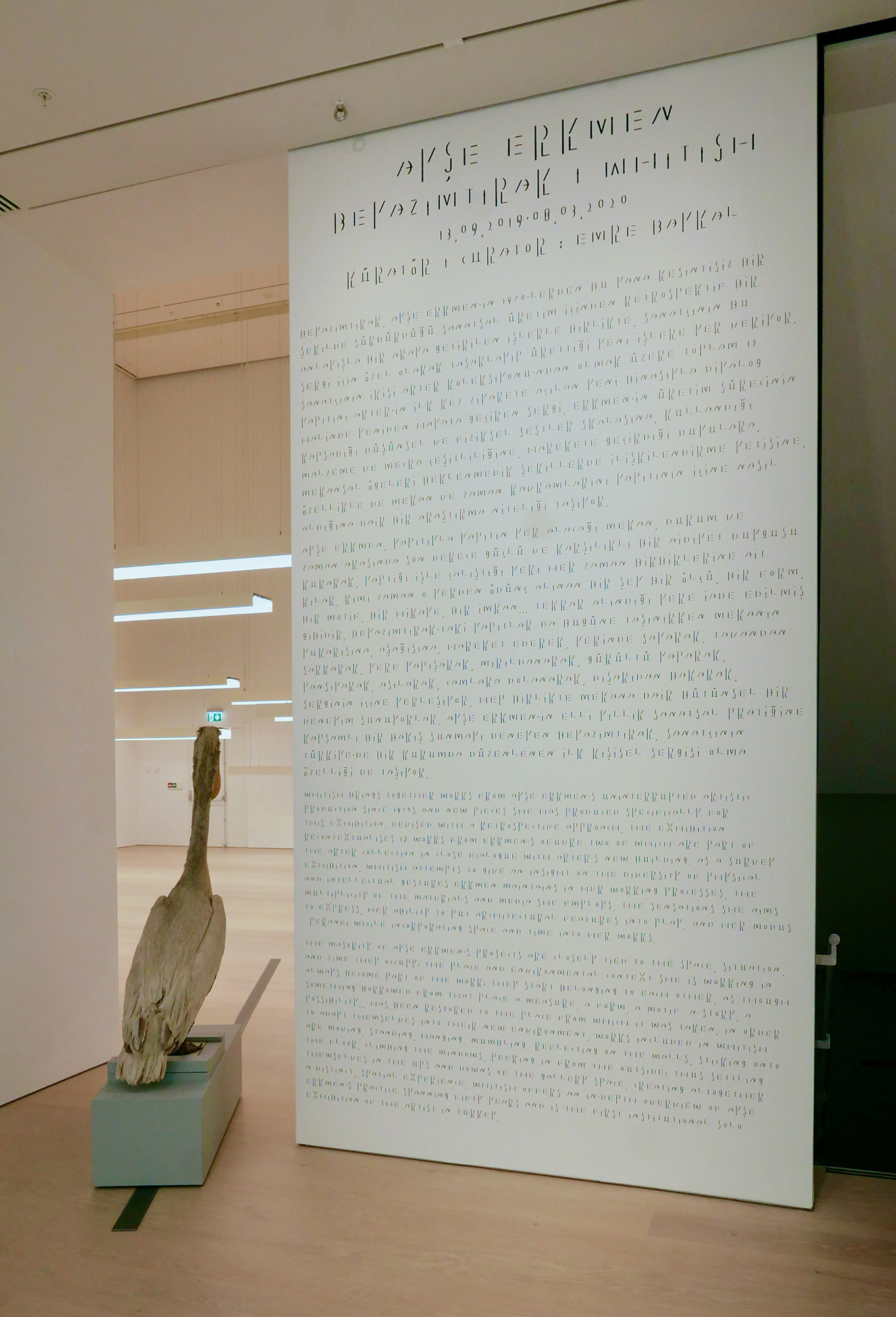

Ayşe Erkmen is best known for her site-specific installations, often graced with her distinct, dry sense of humor. Her projects are informed by a critical approach to installation as a dialogue with the spatial aesthetics of art institutions. Erkmen’s work also emphasizes the abstraction of art contexts, such as the whiteness of the white cube, thus the title of her retrospective “Whitish” at Arter’s new museum in Istanbul.

For this exhibition, Arter curator Emre Baykal worked with Erkmen to adapt her life’s work anew, utilizing her self-referential methods. “Whitish” recalled the breadth of her career, dating back to 1969, including pieces made as a student at the Sculpture Department of the State Fine Arts Academy in Istanbul.

In an Italian restaurant in Berlin, I met with Erkmen to discuss the pieces included in “Whitish,” and why she has never swayed very far from abstraction over her five-decade-long practice.

What was the atmosphere like when you were producing your early works in Istanbul in the 1960s and ’70s?

There was a military government. There were galleries selling paintings; only one gallery was showing work like mine—Maçka Art Gallery. There were lots of galleries, but no critics, no magazines. In the library at the State Fine Arts Academy there was one magazine, Artforum. That was the only magazine we saw.

You could not travel. I had no money to travel anyways, but even if you did you could only go once a year, or once in two years. It was not allowed to travel outside of Turkey. There was nothing you could see.

Did you feel like you were experimenting with your art?

I think so. I didn’t know what I was doing back then. At that time the material was more important to me than the work itself.

The political situation in Turkey, then and now, lends itself to commentary, but you’ve tended to take a non-didactic approach. Why? What are your thoughts on the politicization of contemporary art?

People understand politicized art very quickly. If it is direct, it gives you a feeling of contentedness. If you see a work that is super didactic, you can say, “I’ve done my job for today, and for the rest of the world.” If you put drama in your work it always works because people tend to like things that are political. To aestheticize the drama of the people, and fetishize it, I think is absurd.

I was walking by Oranienstraße in Kreuzberg and noticed your work Am Haus (1994), for which you affixed black plexiglass Turkish text onto a facade. The texts are forms of the Turkish suffix “-mış,” indicating a variant of the past tense denoting hearsay that is used in storytelling. What was the response to Am Haus initially, and what was it like to devise its restaging at Arter’s new space before construction was even complete?

It was 1994 when I produced that. It has stayed since then. I didn’t know that it was going to stay, because it was just for an exhibition for one month. I chose a building where Turkish people are living, so it’s something they can talk about. The people in the building asked if they could keep it, so I said, “Okay, until the next renovation.” But they haven’t renovated since. The installation was made with small nails, therefore I thought it was not really strong. I gave permission to take the texts all out if they fall. Not one of them is falling.

Arter wanted a version of that work in their collection. They wanted to display it on a wall at their collection exhibition "What Time Is It?" in a place where it could be seen from my solo exhibition.

They gave me the plan of the building. My exhibition room changed actually. We worked with the plan, and then slowly the building started coming up and you could understand the space. It’s a difficult space actually because it has extremely high ceilings, the walls are not parallel to each other, there are windows and a bridge. These difficulties which I thought were in the space became a positive in the end. After having completed the installation I realized that this complexity of the space added a lot to my exhibition.

You also remade your Plexiglass Sculptures (1969/2019), which you installed in the center of the gallery for “Whitish.”

I made these sculptures when I was in art school. The curator [of “Whitish”], Emre Baykal, wanted to have very old works; that’s why I included that. The original Plexiglass Sculptures do not exist anymore. Each part of this newly adapted sculpture is based on the plan of the space.

“Whitish” is your first retrospective in Turkey. How was that experience compared to setting up major exhibitions elsewhere?

I’d rather do new work, but I enjoyed working on the Arter exhibition. We had a lot of time to work. The people at Arter, the curators and technical staff, are super. They were more than happy to experiment. I had lot of flexibility preparing this exhibition.

Tell me about your sound installation Dolapdere (2017), which combines recordings of ambient noise from the neighborhood and a voice reciting the names of local shops. The work is very much in dialogue with the neighborhood where Arter is now located.

The sound comes from the titles of all the shops in Dolapdere down and up until Arter; some of these shops aren’t there anymore because of the gentrification that is happening at great speed here.

I grew up and later lived very close to Dolapdere. It’s a poor Roma area. Crime is very high. Unfortunately these shops will not be able to afford to be here very soon and will have to close down. I wanted to make a memory or kind of archive of this area.

The reading of the titles of shops is turned into a sound piece. You don’t hear the names but they are hidden inside this digitally transformed music.

Your digital work, Capable (2019), is a video sequence of stills, clocking in at just under six minutes, featuring your portrait rendered as a virtual avatar enacting various light-hearted gestures. I found it to be a playful adaptation of the GIFs and emojis of contemporary visual culture. Had you created digital art before?

Yes, I had, but not like this. It’s at the end of “Whitish,” and references the animals shown at the beginning [in the ink drawings Elephants, Penguins, Kiwis (2018)]. I draw these animals every day. It’s like an exercise. There’s this term, “kitchen artist,” for someone who doesn’t have a studio. I act as a kitchen artist in the case of the work Elephants, Penguins, Kiwis with quick gestures of drawing. Capable is something light too; you can just relax and think of many things daily and special. And from time to time, as the character often shows up with the question “Why,” one can think of art.

The room in which Capable is shown made for a contemplative setting, for all of its frivolity. At the same time, the sponge benches were awkward to sit in. I thought it added to the exhibition’s subtle comic touch. Was that purposeful?

I made the benches as well. It’s a big statement. That really is the biggest statement [laughs].

For the piece Typed Text (2019), you conceived a new, semi-abstract font for the wall text at “Whitish.” I felt that it reflected a holism between the left-brain comprehension of text and the right-brain appreciation of visuals. Was this your intention?

I wanted that very much. Works are going into each other’s territory, overlapping each other. This was also exaggerated with the help of the piece 100 Stones (1981/2015), taped on the floor. In music, there is the [overtone] sound at the back of the whole exhibition. The stones are doing exactly that job too throughout the space.

The piece Typed Text is quite an old work. To make the wholeness of the exhibition complete we even made a work out of the information wall by using this typeface that I had created out of the signs of a classical typewriter.

Looking back, is there anything about “Whitish” that you feel isn’t right?

With every exhibition you always think, “I should have done this, or taken this away.” But with this exhibition we had a lot of time. There should be fewer regrets because of the time I had.

Do you still teach?

No, not anymore. Teaching takes a lot of energy. You question yourself a lot. You become the biggest critic of yourself. I still can't decide if this is good for an artist or not.

But I know that it’s extremely good to get to know know these young people and their lifestyle, what they listen to, which movies they are watching, what they’re wearing, what they’re thinking, et cetera. They are the ones who know better what’s happening in the world.

I was the kind of teacher who never said, “I don’t like that.” You can have any kind of idea, all are good. The most important thing is to have problems and to transfer these problems and ideas into art.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ayşe Erkmen's “Whitish” is on view at Arter, Istanbul, until April 19, 2020.