People

Sculptural Reincarnation: Interview with Tuan Andrew Nguyen

Drawing on the concepts of reincarnation, material memory, mythology, and storytelling, Vietnamese American artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen works across sculpture, film, installation, and more to explore the lingering shadow of the Vietnam War (also referred to as the American War in Vietnam). In anticipation of his first public permanent sculpture—which will be unveiled in late October at the new Princeton University Art Museum—ArtAsiaPacific spoke with Nguyen in Los Angeles, where the Ho Chi Minh City-based artist is currently spending part of his time to develop further projects. Building upon his series of Calder-esque mobiles made from unexploded ordnance (UXO) leftover from the war, the site-specific commission, titled Naga (2025), will hang permanently in a double-height gallery within the institution.

According to government sources in the US and Vietnam, roughly 20 percent of Vietnam’s land is still littered with UXO. Since the end of the war in 1975, UXO left behind by American military forces has been responsible for more than 40,000 deaths and 60,000 injuries. Our conversation with Nguyen delved into the legacy of the conflict, both physically and spiritually, as embodied in the reverberations of this material that can still be found in various sites across Vietnam, deeply embedded in both the land and cultural memory.

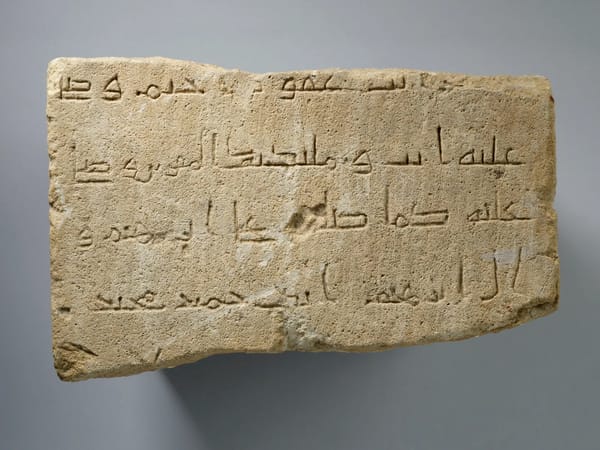

Installation view of TUAN ANDREW NGUYEN’s Naga, 2025, mixed-media installation, dimensions variable, at the Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey. Museum commission made possible by the Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund. Photo by Richard Barnes. Copyright the artist. Courtesy the Princeton University Art Museum.

In your film The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon (2022), the contemporary protagonist, Nguyệt, uses UXO to create these Calder-esque mobiles. At first, she’s not familiar with Calder; then one day, she discovers his work in an old magazine and becomes convinced she is his reincarnation. As it happens, she was also born 49 days after Calder’s death—the Buddhist timeframe for rebirth. How did the idiosyncratic idea for this poignant film come about?

I wanted to create something in parallel with this idea of material reincarnation. In Vietnam’s Quảng Trị province, these unexploded bombs are everywhere, being reused as planters in coffee shops or people’s gardens and backyards. One of the ways that people made a living after the war was to forage and sell this material as scrap.

The film is fictional, but it interweaves the many true stories that we gathered of people who have been affected by UXO, directly and indirectly. Around 2020, we reached out to several NGOs that were involved in demining work, and I had the opportunity to follow one on a big mission where they unearthed a one-ton bomb from a hillside. That experience, and our documenting of it, became The Sounds of Cannons, Familiar Like Sad Refrains / Đại Bác Nghe Quen Như Câu Dạo Buồn (2021), a two-channel video paired with archival footage from the US Navy Seventh Fleet, which is notorious for having fired massive amounts of munitions into the land. In some ways, The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon is a follow-up, portraying certain characters that still deal with these enduring after-effects of war.

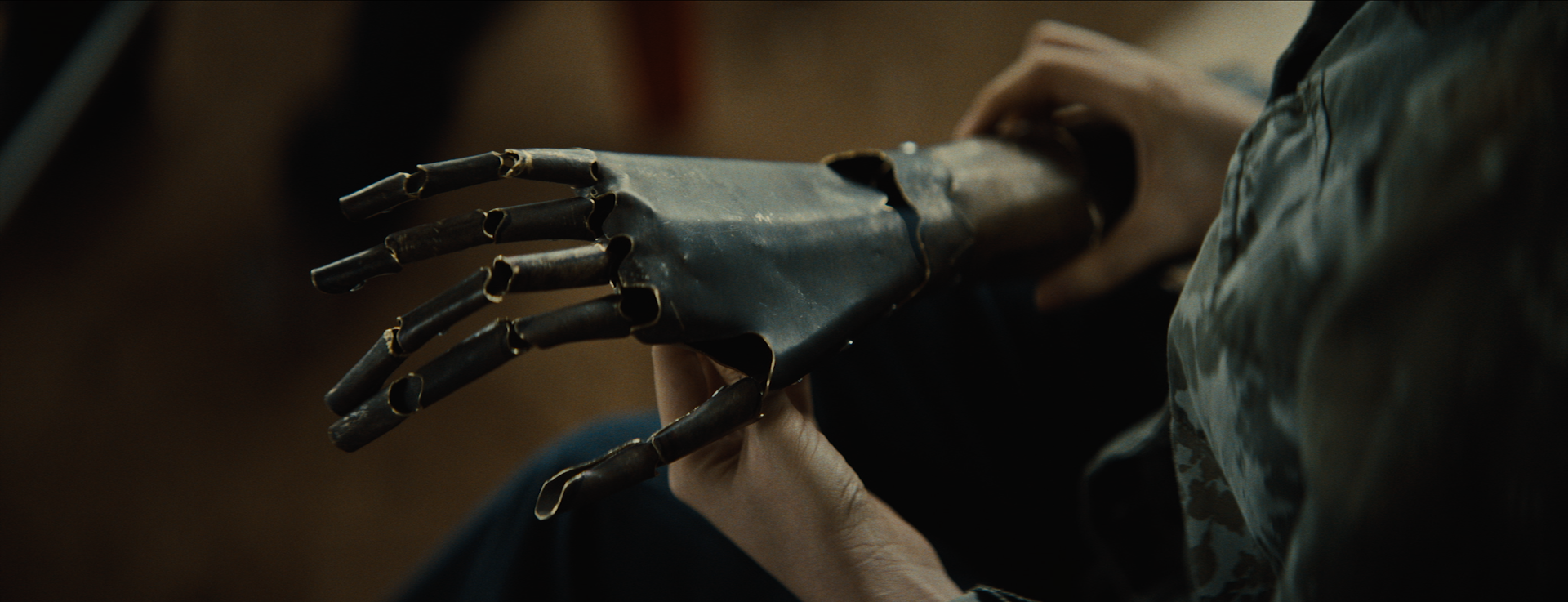

For instance, the character Lai—an amputee who works at the Quảng Trị Mine Action Center, teaching kids how to spot and avoid UXO—is based on a real person by the same name. He was playing with his cousins when he detonated a cluster that took his legs and his arms, and his cousins were killed. He helped me write the dialogue between his character in the film and the protagonist.

The Calder-inspired mobiles, with their arms and branches, in some ways call to mind a family tree, speaking to familial connections, origins, and lineage. Can you tell us more about the genesis of these mobiles and the meanings you’ve derived or discovered along the way?

In The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon, there’s a dinner scene where the main character discusses her sculptures with her mother, and whether or not they remind her of the air raids and bombings from the war. In these mobiles, pieces fall, and even the smaller particles appear to be bursting.

The dainty brass rods connecting each piece in the mobiles symbolize the points between people. Suspended in space, the mobiles are also about unearthing things—whether it’s figural in terms of generations and trauma, or literal in terms of the buried UXO.

I like all of those connections, but materially, the work is also about balance. It took me a long time to understand the mechanics of how to construct a mobile in the vein of Calder. In the beginning, we would make a sketch that ultimately didn’t work. Now the process has become almost intuitive in that I understand the material, as well as the weights and balances of the medium. This delicate equilibrium serves as a strong metaphor that exists in every single piece of the work.

What about your own familial connections? What kinds of things did you—or did you not—talk about with your mother, your father, your grandmother?

It’s in the very title of the film: The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon, which denotes potential catastrophes that arise when you begin to touch upon these traumas. These UXOs are a poignant metaphor for the psychological and emotional trauma that we carry in our bodies.

Alongside this metaphor, the film addresses the physical reality of these buried metals, investigating these highly complicated relationships with the land and this material. We have relationships with each other, but we’re situated on the land, and therefore we have a relationship to the materiality around us.

My father seemed quite different from other men who had served in the war, such as his friends and my uncles. Most of the men from that generation tend to remain silent about the conflict, and are also very strict with their children about not bringing it up. My father only revealed some elements of it, but never told me about his personal experiences.

Growing up in the US during this particular time, I always wished I had an older sister who could explain things to me. Even though my parents were both only 20 years old when they had me, there was a large cultural gap between us. It seemed like they were always trying very hard to move on and assemble their new lives in the US without looking back. So, a big part of my move back to Vietnam was a desire to understand what I felt was a missing chunk of my family history and ethnic heritage. But in doing so, I think I also became a sort of bridge to younger artists or the younger generation, like the older sibling I had always longed for.

What else can you tell us about your new sculpture at the Princeton University Art Museum? What other projects are you currently working on?

We finished installing the mobile a few months ago. We were among the first to enter the empty new building and install art in the galleries.

As for upcoming projects, I’m actually working on my first feature film; we’re currently in the research and writing stage. The film will build on my previous work The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019), which focuses on a Vietnamese Senegalese community in Senegal. It will be based on a very particular person, and similarly comes out of that topic of migration.

Is this why you moved to Los Angeles for the time being—Hollywood!—to make your first feature film?

I’ll go back and forth to Los Angeles more often, but I’ll never say I’m moving back to the US!

That reaction prompts this final question. You and your family came to the US as refugees when you were two years old, but after graduate school, you decided to return to Vietnam to be with your 95-year-old grandmother. How much of that was a political act?

While the choice to be with my grandmother was based on emotional and familial ties, it was also political. When you are in the perceived minority, archiving family history is an inherently political endeavor.

In the mid-2000s, when I was in grad school, the US was involved in a lot of things I didn’t agree with, such as the Iraq War—similar to many things that are happening now across the globe. It all feels cyclical. Right after graduating, I decided, “I’m out of here.”

I’ve been living in Vietnam for two decades now. The first few years were plagued with an overwhelming feeling of loss—you think you’re returning to a place that will offer you a sense of home. And when it doesn’t, because you’ve been away for so long, there’s disappointment. I feel very much liberated from the idea of home now; I no longer feel the need to belong to any specific place in the world. It’s a very Buddhist notion, to feel at home everywhere and nowhere.

Jennifer S. Li is a writer, art advisor, and educator based in Los Angeles. She is also ArtAsiaPacific’s Los Angeles desk editor.