People

Interview with Han Nefkens of the Han Nefkens Foundation

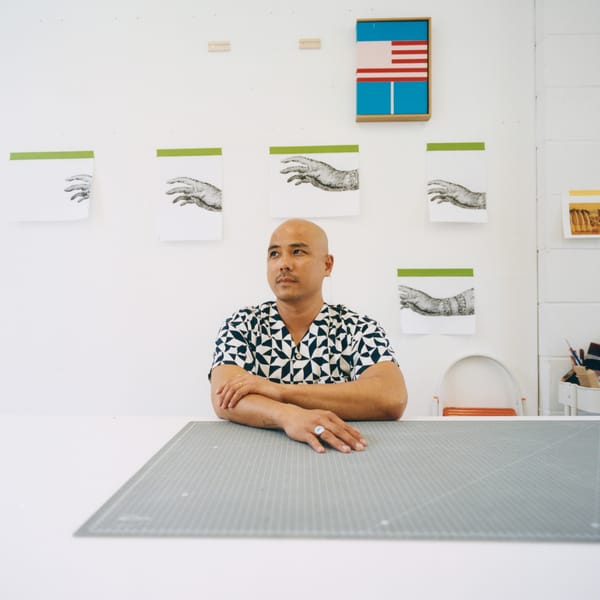

Han Nefkens, a Dutch writer and patron, founded the nonprofit Han Nefkens Foundation in 2009 in Barcelona to foster artistic creation through video art. Unlike traditional contemporary art collectors, Nefkens commissions new works in collaboration with over 50 global institutions, placing artists and the process front and center. Known for its lean, flexible structure, the Foundation supports emerging and midcareer artists by providing funding, mentorship, and exhibition opportunities that enable creative freedom and international exposure. On the eve of Para Site’s opening of “In drawing, in remembrance”—a solo show for Shahana Rajani, who received the organization’s inaugural South Asian Video Art Production Grant—ArtAsiaPacific met up with Nefkens to learn about the Foundation’s outlook on generosity and collaboration.

AAP: What’s the origin story of the Han Nefkens Foundation—what were the series of moments that crystallized your decision to focus on supporting artists making video?

HN: I was brought up in a home with art, but not contemporary art. We were taken to museums when we were young, and I went to museums by myself when I was 10 years old, which, of course, was somewhat of an exception. My peers would go out and play football, and I would go to the museum and sit in front of a very specific painting. I would start a conversation in my head with the painter Kees van Dongen, and create a fantasy about what it was about, who the lady sitting in a café in Paris was in his painting. I imagined that she was Spanish because of her facial features, and that—although she was by herself—she didn’t feel alone as she observed what was going on. Still, deep down, I felt that she was a bit alone after all, so I had to visit her every time I went to the museum, and I always said hello to her. I can’t even say it’s an introduction to art, because growing up, I was surrounded by art.

But in 1999, I went to Paris and saw an exhibition called “Remake of the Weekend” by Pipilotti Rist, which was curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist. I had never heard of the artist before, but I was intrigued by the title. How are you going to remake the weekend? I found myself in this universe created by Rist, with all her videos projected on the walls. She had created a little home, with a kitchen, a living room, and all the videos were cast on the lampshade and on the kitchen cupboards. In the kitchen, I was completely enthralled by the footage and her singing. I could feel the moisture of the ground that she frolicked on, captured in the video. It was a complete environment. When I got out of there, I said to myself, I want to be part of this world. But then I contemplated, how am I going to be part of this world? I’m not an artist, so perhaps I should collect art and then show it to other people, just as it is shown here in the museum. That’s basically what happened. I got in contact with different museum directors so that whatever I would buy would go directly to an institution.

I wanted to educate myself before buying, so I spent one year only looking. The first purchase was in 2001—it was a piece by Rist that eventually went to a museum in the Netherlands. I continued this for a couple of years, and then I started a collaboration with the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. Instead of acquiring art, the museum would commission various artists to create new works. That was my first encounter with commissioning, and we did that for five years. I really liked it because I would be there with the museum’s curators when they talked about the different plans for the artwork, which allowed me to follow the creative process. In the end, most of the work was specifically made for the museum. I liked this process because of the adventure, and also because I realized that this is how you’re really helping artists.

Did they approach you for commissioning, or did you specifically request to be involved in this aspect of the museum?

Now that I think back on it, this is a common thread in my 25-year journey. I would sit together with the director of the museum and several curators, and they would review and discuss the different proposals by a few artists. Finally, an artist would be chosen to receive a commission to make a work. It was the first collaboration for me, which I really enjoyed.

Later, I decided I wanted it to have a structure. I set aside EUR 200,000 (USD 233,000) to commission work for the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen each year, because one of the perennial problems of museums is that they have very little money to purchase or commission work.

That was the crystallizing moment, and then it found different forms. I also supported cutting-edge fashion in similar ways. We helped commission designers like Iris van Herpen, Hussein Chalayan, and Viktor and Rolf. I’m telling you this because it brings me to the video art. Together with curator José Teunissen, who would later become a dean at the London College of Fashion, we made a beautiful exhibition called “The Future of Fashion is Now” at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam from 2014–15, which was then shown in Shanghai and Shenzhen. While it was on tour in China, a curator, Feng Boyi, approached me, saying that he wanted to make a museum exhibition of my private collection of videos. I had never thought about that, but I said sure, go ahead. He curated a beautiful show in Shenzhen in 2017.

And you were still supporting fashion?

Yes, I was still supporting fashion and also doing the patronage with the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. I set up a scholarship for Spanish writers, started an arts initiative to support AIDS research, among all sorts of other things. And when I walked into that museum—it was like the Pipilotti Rist experience—there came a second turning point: It was the He Xiangning Art Museum, which was all glass, and each video had space. I stood there, just as I had stood 16 or 17 years earlier at the museum in Paris, and I said to myself, “Yes, this is what I want to do from now on—only video.” Since then, all my attention and financial possibilities have gone into producing video. That was one of the best decisions I ever made.

Why?

Because I was finally focused. It’s a niche. Today, more foundations support just video art, but at the time there weren’t that many. There was a great need. The first idea I had was “I’m going to help produce videos.” Then I had to understand “How are we going to do it?” Hilde Teerlinck, the director of my Foundation, thought we could help artists by financing the production, but we can also help them just as much by finding different venues to show the work. As a result, we had the idea of grants and to collaborate with five or six museums to select an artist who would produce a work, which would then be shown at one of these museums all over the world. We’ve been doing that for 10 years, and it’s a growing initiative. We have smaller grants endowed with USD 15,000, but now we also have commissions that range between USD 100,000 and USD 120,000 for more substantial works with museums that collect. Those are four groups of museums from around the world, each of whom commission—M+, Mori Art Museum (MAM), Singapore Art Museum (SAM), Museo Reina Sofia, Walker Art Center, MACBA Barcelona, MUAC, UNAM, Mexico City, The Bass, Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA), The New Taipei City Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, and Art Sonje. The museums each get a copy of the video for their collections.

Speaking of grants, what was the genesis of the South Asian Video Art Production Grant, and how did you come to choose Shahana Rajani as your first recipient of this grant?

We had a jury meeting with the curators. The first time we met was in Dubai with the Ishara Art Foundation, with people from Prameya Art Foundation, New Delhi; Nottingham Contemporary, UK; M HKA in Belgium; Para Site in Hong Kong; and the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. Now we do most of these jury meetings via Zoom, but back then, we met up in person because the participating museums didn’t know each other. Hilde and I, together with the different museum curators and directors, looked at the shortlist of the different candidates. For this Grant, the longlist is provided by scouts in South Asia, and then a shortlist is made. The deliberation takes one day, and the different museums talk about why they want one artist or the other. The decision is never made through a vote. I don’t believe in voting, because every museum must be absolutely convinced that this is the artist they want to work with. You cannot impose it—that’s not a good idea. It became obvious it was Shahana: she was given a grant to produce the video, and now it’s being shown at Para Site.

None of the artists who receive your grants or commissions are chosen based on finished works, so are they proposals?

They’re not even proposals. When we talk during the jury meeting, they’re just artists we are considering and what they’ve done so far. When I say we, I should actually say, they.

Because you don’t believe in voting, and you don’t get a vote.

Exactly. I don’t get a voice, let’s put it the right way. It’s really a question of trust, which is so helpful for artists. That’s the practical part of it. But that there is a group of experts who decide that this is the artist who will receive a grant because they believe that the artist will make a work that’s worth showing in the different venues—that is the responsibility. Yet ultimately, it’s also a sense of trust—both between other museums and in the Foundation. For me, trust is the basis of collaboration. If you don’t trust somebody, you cannot collaborate with that person or that institution. I feel very strongly about this.

How did you decide on showing her work at Para Site?

The Foundation makes that happen because we know the directors, or we meet the directors. It’s organic. For us, it’s really connections, and it’s not for everybody. It’s a certain kind of institution, a certain kind of person that is interested in collaborating, making a choice together, and the adventure of not knowing what they’re going to show.

What kind of organizations do you feel are open to this process?

Well, look at this collaboration. In Hong Kong, there are M+ and Para Site: very different organizations. We have big museums and we have smaller artist initiatives because I think they really need our support. It’s organizations that are willing to trust and have the same flexibility.

Are the works that you commission with M+, SAM, and MAM different than what you’re doing with Para Site, for example?

Yes, they are more midcareer. The USD 15,000 grants go to a smaller organization and to an artist who hasn’t had the opportunity to show. For the USD 100,000 or USD 120,000 commission, on the other hand, you want somebody who knows how to deal with that. Those are the kinds of artists that institutions like SAM and M+ would like to show.

With the commissions, these come about through recommendations among museum curators. It’s more controlled, slightly less organic, because it’s such a big budget and an important institution.

But one interesting thing that has only happened once, is when Hao Jingban won the ARCO Madrid Video Art Production Award in 2019, and later in 2023 was selected by MAM, M+, and SAM for the Moving Image Commission because her practice had evolved. It could happen again.

Do you have set criteria with which a scout can suggest an artist, or a curator can nominate for the commission?

No, there is no criteria with the grants, except the age, which goes up to 40 years. With the commissions, it’s generally up to 35 years. Grants are always geographically based, and the commissions are in some cases geographically based, but occasionally they’re theme-based.

The artist who gets selected is the choice of the directors and curators of the venues. It’s not my choice, so I learn. I get to see the work, learn to understand it, and this broadens my scope as well.

Do you ever feel compelled to buy a work by one of the artists the Foundation supports with a grant or commission?

No, I stopped collecting 20 years ago. I just want everything to be clear and transparent. The Foundation doesn’t ask any of the artists who receive a commission or a grant for a copy of their video. If I would like to watch it, I can just ask for a link. Plus, that leaves the artists a possibility to sell an extra copy, right? If they gave a copy to the Foundation, they would have one copy less to sell.

You don’t make any stipulation about whether they can sell their videos?

It’s better to have no rules. You have to see how it goes. For instance, Shahana has these small objects for sale at her Para Site show. They were made by people from the community that is the focus of her video. It’s a beautiful gesture because it continues this link with the community, which benefits them as well.

Was there an unexpected insight that occurred after reviewing Shanana’s past work or her practice, which you remember?

It’s all about intuition. The curators look for an artist who has their own voice that distinguishes them from others. They stand out because of that, whatever it is, and this was the case with Shahana. There was this integrity in her work—the way she approached her subject was always with great respect and involvement. Plus the content, which she’s always shown in communities. Moreover, the aspect of how much this will mean for the artist’s career also comes into play.

You mentioned that for the Foundation, it’s not just about giving money to realize a work, it’s also about helping the artist get visibility. With an exhibition like Shahana’s at Para Site, how do you structure the Foundation’s support to maximize that potential for an artist?

The financial support produces the work, and then it’s up to Para Site to make the exhibition. We also help promote their work as well as the organizations we work with through the Foundation’s PR and communications.

It’s a very organic process that we’ve looked into. For instance, regarding the grant, there are 39 artists who have received it so far. The work has been shown in five or six venues all around the world. But that is only the beginning, because we move around a lot. We meet people, and we talk about the artists, and they say, “Oh, that’s interesting. Why don’t you give me a link to the videos of the artist?” We recently asked around five artists we’ve worked with in the last two years what has happened since getting the grant, and we found out that they have shown approximately 20 to 24 times, and their work has been bought by museums. They’ve also received other commissions and awards. This really is only the beginning. The more we’re able to connect with other people in the art world, the better it is for our artists.

It’s much more than these five or six venues that you have chosen to work with. Most wouldn’t realize that, and you probably don’t even take credit for that.

We don’t need to get credit for that, as long as they show the artist. That’s the most important thing for us.

Every week, we get requests for links to the artists’ videos, and we’re more than willing to share them. All 45 art institutions that work with us have links to the projects we produce, and they share them with other art institutions as well. It’s open in that sense, so anyone can watch the work for two weeks.

Even the artist who doesn’t get the grant or the commission is being helped because curators from different museums see their name on the longlist or shortlist. So then, if their name or work appears in another situation, at least they know about them. The videos on the longlist are also available as links. Whoever wants to see one of the videos can do that whenever they want. It’s helpful for all the artists.

That’s a lot of valuable research that you’re sharing, because of the scouts you invite, who are also very knowledgeable about the artists and the kind of works they make.

That’s one part of why it’s attractive for the art institutions to collaborate with us, because for each project, there are always these scouts who have the time and reason to do all this research.

What daily activity or practice keeps you in touch with the artistic, emergent voices that the Foundation is interested in?

It’s talking to people, being open. I stay in touch with the artists that we work with, to talk about what they’re working on. Another thing I love so much is when these different artists meet each other through us, and then they become friends: it’s a community.

I also write every day. This is why I can very much relate to artists when they have to make a proposal. I really understand how difficult it is to use the proposal as a map for the journey, because once you start, you might want to go a completely different way. The proposal is perhaps an intention at the moment, but in the end, it might be something very different. We leave our artists alone with that liberty to change directions.

Video is very similar to writing.

Yes, that might be why I’m so attracted to video—there’s a start and a finish. But the interesting thing is that there’s something in-between that beginning and ending that’s unique to each artist. It can also tell us a bit about the different cultures—for example, how time is experienced in varying ways. For us, it’s very linear, while in other cultures, it is a much more circular concept, and there’s no tension arc that we are used to. It’s fascinating to learn about what you don’t know.

Many of the videos that you have commissioned give you deep insight into histories that are not widely known or even visible.

Like Shahana, what did I know beforehand about the fishing village that was displaced or the river that was moved? Nothing. I also didn’t know how important painting was in that community, which includes several painters, particularly one elderly man, whom you can see in the video. Everyone respects him for his artmaking; they ask him about it, and he talks with them about his work in the video. Though I’m in Barcelona, sitting behind my computer, I’m suddenly in Karachi, living this history. And this beautiful history and these ideas bring back what was lost through painting.

What kind of unexpected lessons have you learned from working with the artists the Foundation has supported? What draws you in, and how has it shaped the Foundation’s mission?

When I talk about things happening organically, it’s a question of collaboration. It’s not about forcing things, but adapting to circumstances. What we also learn is respect for other people. This is what I get from the jury meetings.

I think we’ve really changed how we’ve done things over the last 10 years because of the subtleties involved in our collaboration with everyone. For instance, that’s why we call them grants or commissions, not awards. Because an award means that somebody has won and others have lost. These are grants and commissions, and they are not winners per se, but recipients. I find that distinction very important.

Another thing we always do after a jury meeting is that we tell the artists who have not been selected why it went this way, or what the considerations were. Sometimes it doesn’t even have to do with the artists themselves, but with the other artists—such as you’ve had more opportunities to show your work, or we think you have access to funds in other ways. But it’s very unsatisfying for artists to only hear that they didn’t receive the grant. For us, it’s about respect, which is very critical.

I know you’re not goal-oriented, but how do you measure impact in a field that’s so intangible?

That’s a very good question. It’s a question we ask ourselves, and that’s one of the reasons why, half a year ago, we asked around five of the artists who received our grant how often they show the videos that we produced with them, because we wanted to measure our impact.

But is this the endgame? Would you still do this work regardless of whether you asked this question about impact?

We asked this question about impact because we were having a board meeting. We felt we should present something to the board and explain what we’re doing, so we wanted to investigate this. The six venues that we collaborate with already guarantee six shows, which I thought was good enough. That’s why I was so surprised when I heard that these artists have exhibited their work on average at 24 other venues.

Let’s say you meet someone who wants to start doing something similar to you and your Foundation, but has limited resources. What would you suggest?

I would suggest getting together with a group of friends, because then you have more money and also more fun. It’s nice to do something together with other people, and that keeps the momentum going. Then, you could get together with a curator from an art venue and talk with them about the ways you could help an artist.

Next, let’s say you find 10 friends, and you each put in USD 2,000 a year, so you have USD 20,000—that’s quite an amount that you can do something with. You could invite an artist from abroad to come to Hong Kong, for example, and have a residency here with that money. You could help an art institution by financing a publication together, so you have the residency, the publication, and the production of work. The whole idea would be to really focus on the joy of collaborating—collaborating among your friends, collaborating with an art institution, collaborating with the artist, meeting new people through the projects that you undertake. That’s just the beginning. But getting together with other people, that’s really important and so much more fun.