People

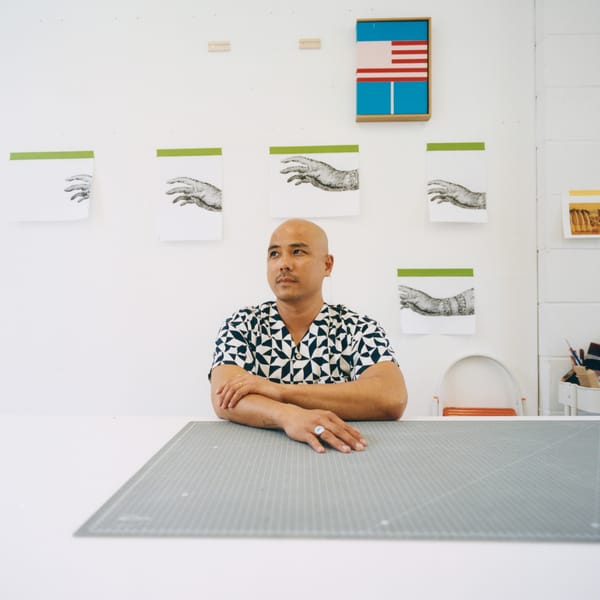

Hope as Practice: Interview with Tony Albert

Renowned for his sharp wit and powerful use of found objects, text, and assemblage, Tony Albert addresses legacies of racial and cultural misrepresentation in his multidisciplinary practice. The Girramay, Yidinji, and Kuku Yalanji artist is at the helm of the fifth National Indigenous Art Triennial, “After the Rain,” which recently opened at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, contemplating the quiet cycles of healing and regeneration. In this interview, Albert discusses reclaiming narratives around Aboriginal identity and visibility, and how optimism can serve as a tool for resistance in times of global calamity.

AAP: Throughout your career, you’ve critically engaged with the (in)visibility of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, notably remarking, “Invisible is my favourite colour.” Could you elaborate on the sentiment behind this statement?

TA: That phrase came from a place of frustration but also transformation. It acknowledges how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have historically been effaced in Australia’s cultural landscape, and also reclaims that invisibility as a kind of power. When something is unseen, it can’t be contained—it becomes everywhere and everything. “Invisible is my favourite colour” is about stepping into the light on our own terms, asserting presence in spaces that once erased us. It is both an act of visibility and defiance.

How does your artistic process differ from your approach as a curator or artistic director?

As an artist, I’m guided by instinct, which is rooted in emotion, humor, and lived experience. As a curator, I become a listener and a facilitator. Both roles share the same foundation of storytelling. The difference is that curating asks me to step back and hold space for others. In “After the Rain,” I see myself as a gardener, nurturing ideas, ensuring artists have what they need to grow, and doing whatever is humanly possible to bring their vision to life. It’s a balancing act between vision and humility.

In a previous interview, you mentioned the importance of ensuring there are “appropriate cultural protocols and nuances in place” when presenting Indigenous art. What does that involve?

Respect and listening are the heart of any First Nations project. When we speak of protocols, it’s not just about permissions, it’s also about relationships, care, and accountability. It means asking, “Who holds this story?” and making sure those voices lead the way with autonomy. In “After the Rain,” every decision (from artist selection to installation) was grounded in consultation. Cultural protocols ensure we don’t just show Indigenous art, but that we work in Indigenous ways with Indigenous people.

First Nations art is gaining more traction worldwide, with major international exhibitions bringing overdue attention. Do you feel any apprehension about Indigenous art potentially being commodified and mindlessly consumed within the global art industry?

Visibility is powerful, but it also carries risk. When the world finally looks our way, we must ensure it’s not a fleeting gaze, and that the outcomes are both ethical and sustainable. The danger is when Indigenous art becomes a trend rather than a truth. My hope is that the focus remains on story, sovereignty, and context, not consumption. True visibility must be reciprocal—it should lead to understanding, not extraction. I do believe there is a global push in First Nations art that is being significantly led by Australian Aboriginal artists and cultural workers.

Installation view of ALAIR PAMBEGAN (Wik-Mungkan people)’s Kalben-aw story place of Wuku and Mukam the flying fox brothers at the fifth National Indigenous Art Triennial, Kamberri/Canberra, 2025. Copyright the artist. Courtesy the artist and Wik & Kugu Arts Centre, Aurukun.

The National Indigenous Art Triennial, “After the Rain,” explores ideas about rebirth and cleansing cycles. How did this title and concept come to be?

The title came from a deep reflection on renewal. After the rain, the earth breathes again, country glistens, the air changes, and what was dormant awakens. For me, “After the Rain” symbolizes that moment after struggle when hope quietly returns. It’s not naive optimism, but faith in cycles of healing. This triennial asks: what comes after? What do we grow next? It’s both a question and a prayer, and it offered a poetic curatorial spectrum that artists could engage with in multiple ways. While some responses are very “on country,” others consider what “After the Rain” means in relation to the 2023 Australia referendum, when a majority of Australians voted against Indigenous recognition in our constitution.

While the previous triennials have often confronted histories of injustice, “After the Rain” feels more forward-looking. How do you maintain optimism as the world faces sociopolitical turmoil and climate crises—and how does this exhibition respond to these contexts?

Optimism isn’t the absence of struggle; it’s the decision to keep imagining. Rather than ignoring hardship, “After the Rain” leans into it and asks what renewal can look like. Artists remind us of possibility, even as the world feels heavy. For me, hope is an act of resistance. When we create, when we laugh, when we plant something new, we’re declaring that a better future is still possible.

In the publication about “After the Rain,” you and Sally Brand reflect on Albert Namatjira’s legacy, recounting how you both traveled to Ntaria to visit the late artist’s house. How did this experience influence your outlook and process of organizing the triennial?

Standing in Albert Namatjira’s home, surrounded by his landscape, I felt the weight of both history and continuity. His work opened a door for so many of us; he painted Country through his eyes and invited the world to see its beauty. That visit was profoundly humbling and shaped “After the Rain”: it reminded me that every act of creation is also an act of return. We stand on the shoulders of those who painted before us. Through his exceptional talent, Albert Namatjira was the first Aboriginal person to be granted Australian citizenship. He was an entrepreneur and wanted so much better for his family and community.

As First Nations artists receive more mainstream recognition, how do you navigate the paradox of visibility within colonial-capitalist frameworks? In what ways will the triennial set up a platform for dialogue rather than mere representation?

Recognition is complex when the systems that frame it weren’t built for us. We’re grateful for visibility, but we’re also reconfiguring what those spaces mean. “After the Rain” isn’t just about representation, it’s about self-determination and giving artists a platform to speak with rather than be spoken for. I still see great potential and opportunity to knock down walls between cultural institutions and the many artists they represent.

You’re a founding member of the Brisbane-based Aboriginal artist group proppaNOW. How has the experience of working in a collective shaped your individual practice?

proppaNOW was born out of necessity. We wanted to create a collective where we could speak freely and unapologetically as urban Aboriginal artists. That community taught me the power of solidarity and humor and the collective strength in how to push back together. The spirit of proppaNOW continues in everything I do from collaboration, provocation, and care. My next projects continue that thread of connecting artists, building platforms, and finding joy in resistance.

In your work, humor serves as an important tool to confront the legacies of racism and colonialism. Why do you use humor to address such difficult topics?

Humor is medicine. It disarms, opens dialogue, and makes truth palatable without losing its sting. When I use humor, I’m flipping the script on racist imagery, reclaiming it with laughter. That laughter isn’t a dismissal; it’s a kind of survival. It says, “You can’t hurt us anymore.” Humor gives us agency—it’s how we take back power and heal through joy. I feel it is like a guerrilla tactic, and it works better for me to make someone laugh than to yell or point the finger.

You and Sydney-based artist Nell recently unveiled a permanent outdoor commission at Brisbane’s Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, titled The Big Hose (2022–25). Could you tell me more about its connection to the story of Kuril the water rat?

The Big Hose began as a playful idea and grew into something deeply symbolic. Nell and I worked with the local community, connecting the project to the story of Kuril the water rat, whose spirit animates that part of the river. The twisting hose appears alive, and it’s also a play sculpture; a meeting place where culture, collaboration, and curiosity converge. I love that children will climb and laugh upon it because joy, too, is a form of legacy.

Annette Meier is an assistant editor at ArtAsiaPacific.