People

Broken Form, Unbroken Faith: Interview with Lam Tung Pang

“It is always the situation that ‘construction’ and ‘deconstruction’ are a pair of forces. I always have them in my work, but they have become increasingly intense recently.”

– Lam Tung Pang

Transplanted creatives often describe leaving home as a process of taking step after step away from the familiar into an unknown landscape, until, looking back, they realize how far they have journeyed. In his inaugural solo exhibition at gdm Taipei, “Everyone’s journey toward faith is different,” Lam Tung Pang used this process of gradual removal as a framework to interrogate his formative experiences in Hong Kong, and to contemplate his future in Vancouver from a position of geographical and psychological distance following his emigration to Canada in 2022.

Through this lens, Lam works to dismantle and rebuild the accumulated layers of his inherited artistic and cultural patterns, the complexities of self-imposed exile, and the ongoing negotiation between autonomy and optimism amid pervasive instability. The exhibition became a site of deconstruction and personal reflection, as well as offering a platform for Lam’s existential inquiry into the dynamics of tradition, displacement, and resilience.

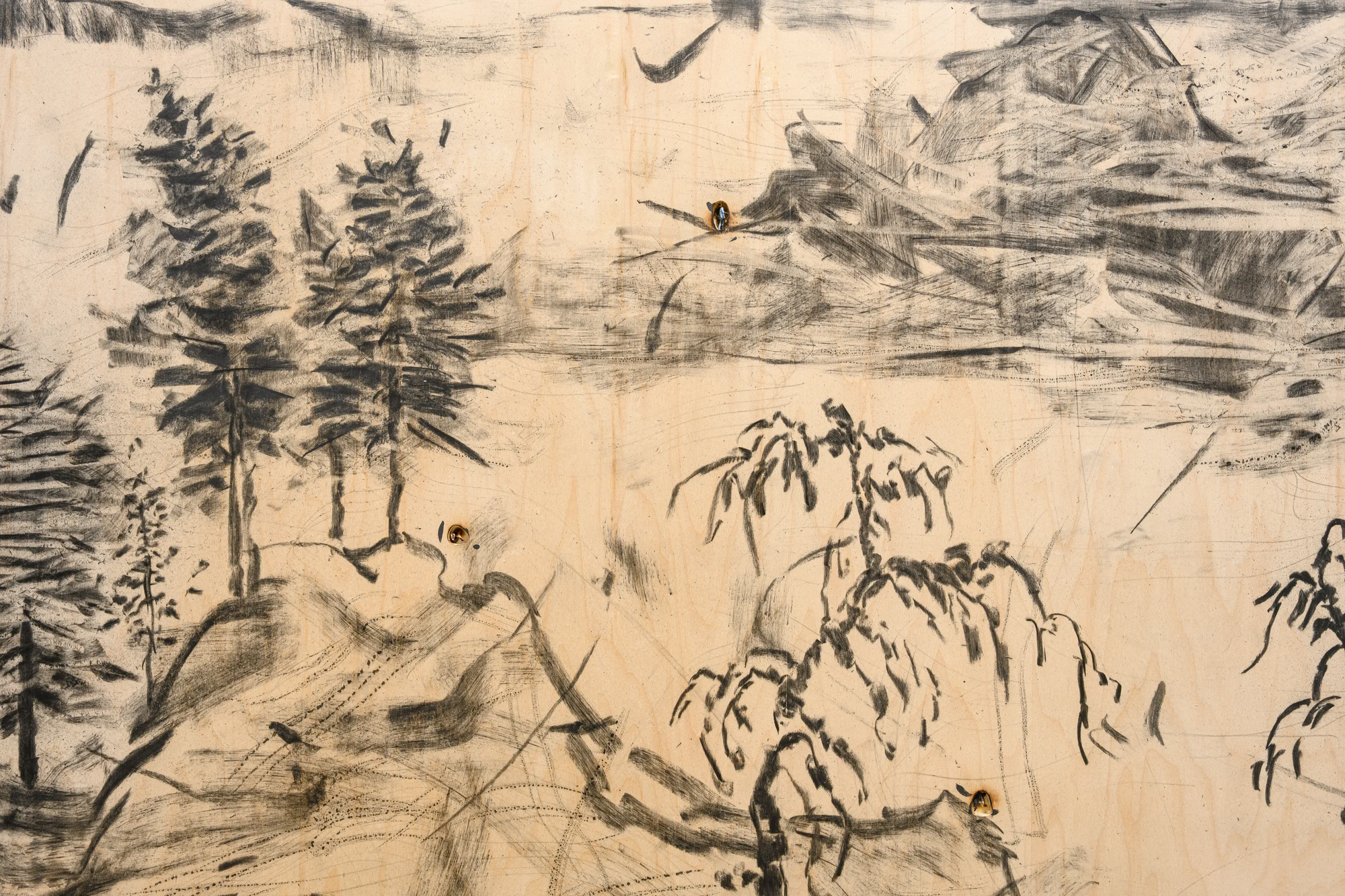

Eight artworks, seven created and reinterpreted after Lam’s departure from Hong Kong, played with the generous proportions of gdm Taipei’s exhibition space, with Mountain De-w #1 (2023– ) incorporating the corner between two walls into its broad, chaotic vista of fragmented brushstrokes, while A Tree Found in Revelstoke’s (2025) precariously stacked plywood panels curve to be contained by the floor and ceiling. For his first solo presentation in Asia since 2022, Lam created two of his most monumental and ambitious works to date, Dwelling in Fuchun Mountains (Rebuild) and Praying Hands (both 2025)—respectively drawing from the 1350 Huang Gong-wang and the 1508 Albrecht Dürer masterworks of the same names.

Installation view of LAM TUNG PANG’s “Everyone’s journey toward faith is different” at gdm Taipei, 2025 (left); and detail of LAM TUNG PANG’s Praying Hands, 2025, kinetic sculpture, plywood, UV-print, motor, wires, 3.5 x 3.55 x 1.6 m. Courtesy gdm Taipei.

The original Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains was selected by Lam as an appropriate symbol to probe concepts of “home” and “relocation,” as it is currently split in two between the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou, and the National Palace Museum, Taipei. Refracted through his iconic “broken stroke” style, the contentious, canonically venerated landscape is reinterpreted into a new form, changed yet whole. Opposite is the nearly four-meter-tall kinetic installation Praying Hands, a composite image of hands in prayer composed of 23 individual fragments of wood hung at different heights—each painted with a knuckle, fingertip, or palm. Every four minutes, the composite form becomes fractured, disintegrating as a motor rocks the articulated puzzle of joints causing each component to shift and swing past one another, complicating one-note readings of prayer.

Far from only being a reflection on sorrow or nostalgia, Lam’s new period of “faith” presents a consideration of deconstruction as a driver for constructive experimentation with new techniques, subjects, and approaches to pre-established, canonical, and personal artistic traditions. This exhibition invited viewers on a sojourn through a landscape of chaos and hope, located somewhere between Revelstoke and the Fuchun Mountains.

In the exhibition title “Everyone’s journey toward faith is different,” is it a specific kind of faith that you’re referencing? Or is it a more general hope that things will improve?

When I think about faith, it’s not in a particularly religious sense, or that there is an image of God out there. To me, “faith” is more about how, through action, something brings you hope, especially in these chaotic times. The world is so broken, I have to use my broken language and broken stroke to describe it. That became one of the main themes of this exhibition.

I came up with the title after reading it in a [religious] book. Everyone has their own pathway to finding faith. That really inspired me to create this work.

What, then, is the significance of referencing Albrecht Dürer’s Praying Hands as opposed to other symbols of hope or faith?

Firstly, it is a very famous and recognized image. I thought about hands and that, when you’re praying, it’s probably because of the very unstable world that we live in. It is a simple gesture that also communicates how anxious and unsettled we are.

I thought about the motion, the construction of the hands, and came up with the idea that they would always be moving—as if you’re begging, or finding your faith, or praying to someone. But at the same time, they are shaking and unstable.

In invoking Huang Gong-wang’s Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains and Dürer’s study of Praying Hands you allude to iconic, distinctly recognizable pieces of work from both Western and Chinese traditions. I believe this is the first instance in which you explicitly refer to a Western artwork. What prompted such a wide frame of reference?

These references have been in my mind for a really long time. At university, I studied Chinese, European, and American art.

When I come up with a new idea, I draw on all these images that I learned about. But now, in retrospect, I have begun to question these specific art histories and learning processes. While I’m still relying quite heavily on American, European, or Chinese art as a reference, I feel that, in a way, I’m deconstructing myself now.

My reference to Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, for example, is only a starting point. That is, you start from inspiration, and then leave it alone before you create another “layer.” Here, I added many different elements, ranging from plants to trees and figures. All these “layers” are not only based on the past, but derive from our contemporary experience. History should act like a pair of glasses that shape the way you see the world.

Still, you have to open your heart and mind to the versatility of history. The relationship to a bygone era versus where we are now and how we currently understand the world—that is actually the other layer based on so-called “historical references” or “images.” Timelines are not always linear; there are always overlaps that engender new meanings.

All of this, for me, is like a scar that we carry through all this trauma that we experience, under the narrative of history. We’re part of it, and we probably suffer from that, too. It shows how we accept this kind of deconstruction, and how we realize faith.

So you’re creating a personal canon by drawing from what helps you express what is happening in the moment.

I think that is the most important aspect. As a living artist, you are not an artifact in a museum. We deal with everyday life. So all these layers of feeling and experience are crucial to me. When you’re quiet, you start to think and digest all this experience and meaning.

A Tree Found in Revelstoke (2025) has also been dubbed The Trees of Grizzly Town. What is the significance of this reference?

“Grizzly Town” is a misnomer for Revelstoke. It’s a town in British Columbia, Canada. It used to be an essential location for the railway industry that connected the East and West in Canada.

I visited the town, and I saw that tree in the park. It looked very strong, yet also thin and frail. Like I said, those are a pair of forces, right? Strength and fragility together. So, I think this image really captures how I felt at this point in time.

Is your recent self-exile to Canada already contributing new “layers” of experience to your work and subject matter?

Absolutely, because it is a completely new situation for me. Living in Hong Kong, everything was located within a two- to four-kilometer radius, from my kindergarten to my university, to my studio and my working space. It was just such a small area. So, for me, this move to Canada has been expansive.

There’s also the image of Hong Kong… it’s always a process of memory and loss. I think of it like a landscape: there’s snow on the tip of the mountain, and when the summer comes, it all disappears.

Having worked on landscapes for a very long time now, I have this idea that landscape and home-building are all tethered to the same cultural concept.

Do you find yourself revisiting previous works or the periods in which they were created?

Because I carry the language that I developed through those places, these moments are always in my mind. I think self-exile or being away from your hometown are not completely connected—as you said, it is kind of a process of looking back at those works, but at the same time they are looking back at you, and also looking forward.

One of the great things about moving to Canada and being in a kind of self-exiled or diasporic Asian community is that you value this kind of connection with your past and with people more.

Finally, how do you view yourself and your experience as a “diaspora artist”? Do you see your experience of leaving home as singular to you, or do you perceive your work in context with other diasporic artists who have continued their practice abroad?

I think it’s very simple: I carry the culture that I have with me everywhere, but it doesn’t mean that I must stick to that culture forever. Culture also is a living agent; it can change from time to time, from location to location. I don’t take the language that I have as a burden—I just say, “It will be my inspiration.” With this inspiration, I can just keep on going to create more work.

I see a lot of Chinese artists or classical artists in Canada who become homesick. They freeze in the moment of time when they left their hometown. In my case, I just think, “Okay, it happened.” But you must carry your language with you. You have to live your own way, always ready to be open. And once you open up to that space, then you will have the room to accept anything.

Brynn Gordon works in Hong Kong specializing in modern and contemporary Asian art.