Issue

Of Sound and Identity: Christine Sun Kim

Christine Sun Kim’s solo exhibition “All Day All Night” at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York resisted the conventions of a midcareer survey. Instead of tracing a career arc, it immersed viewers in a dense spatial and conceptual vocabulary. Comprising 95 works made between 2011 and the present, the show brought together charcoal drawings, murals, video installations, and sculptures, all orbiting a central theme: sound as social currency. Kim, a Berlin-based American artist who is Deaf, confronts how sound can be wielded for power, privilege, and exclusion.

One of the first works on display, the mural Ghost(ed) Notes (2024), greeted visitors with a sprawling array of musical notations. Instead of the standard five-line musical staff, Kim employs a four-line staff, visually echoing the feeling of being “ghosted”—when communication abruptly ceases without explanation. The musical notes hover just above and below the staff but not within it, emphasizing the sensation of being near, yet fundamentally excluded. Her four-line staff acts as a rejection of the prevailing standard, a reconfiguration of who gets to participate in the act of “listening.”

That idea—of living outside dominant systems—permeated the show, which was organized nonetheless by a high-level, multi-institutional team: Jennie Goldstein, associate curator of the collection at the Whitney Museum; Pavel Pyś, curator of visual arts at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis; and Tom Finkelpearl, former commissioner of cultural affairs for New York.

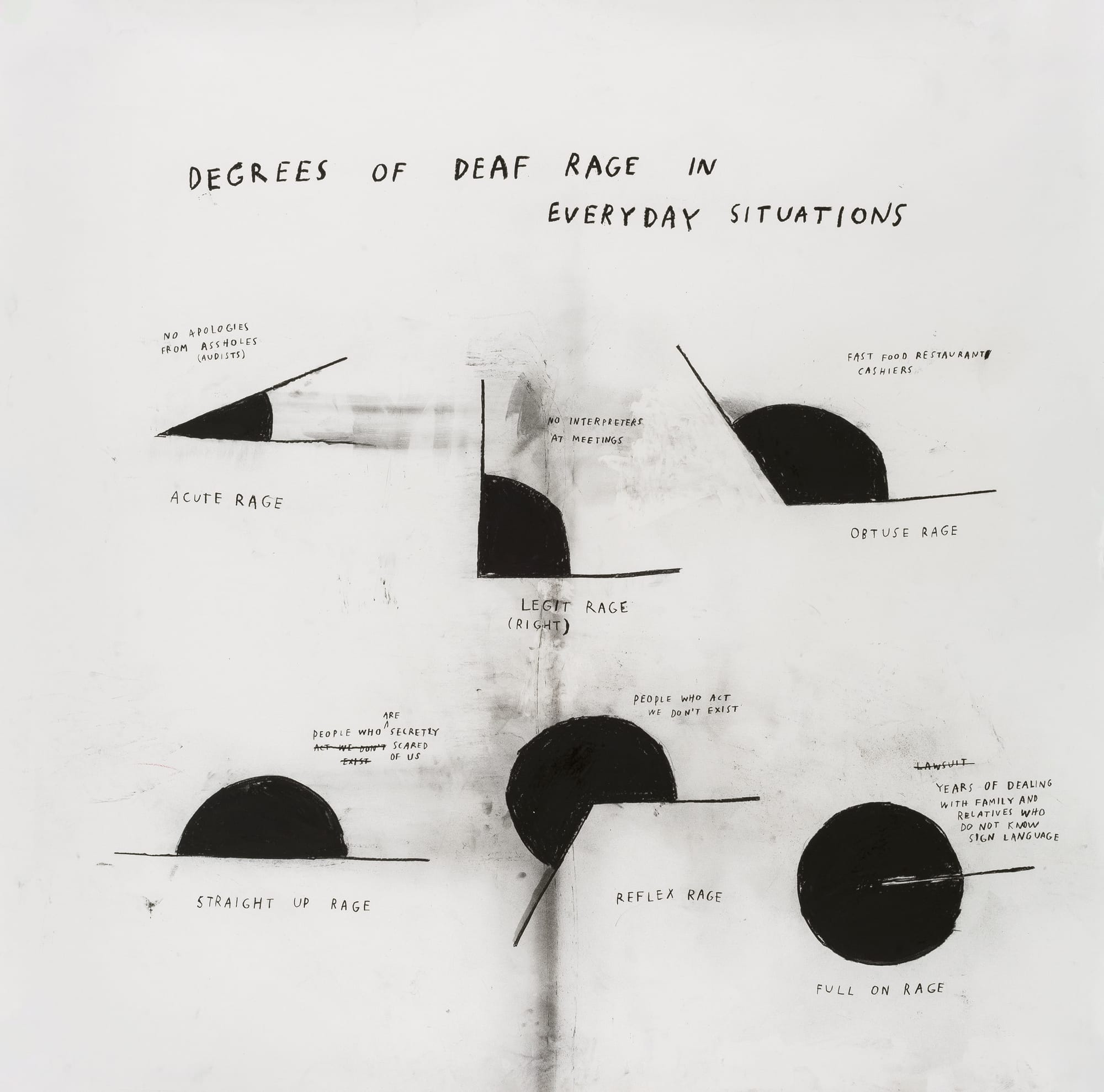

In her schematic image-and-text drawing Degrees of Deaf Rage in Everyday Situations (2018), Kim geometrically apportions the emotional toll of navigating a hearing-centric world. The pie chart ranges from the narrow-slice “acute rage”—a reaction to “no apologies from assholes (audists)”—to “full-on rage,” reserved for “years of family and relatives who do not know sign language.” The composition is visually aggressive, with thick charcoal smudges and rough forms reinforcing the intensity of Kim’s frustrations, displayed under the word “lawsuit” with a line through it.

Degrees of My Deaf Rage in the Art World (2018) shifts to industry-specific grievances: from “acute rage” at a Guggenheim accessibility manager, to “full-on rage” over museums with zero Deaf programming and no Deaf docents or educators. The “rage” pieces are both biting and humorous, an inventory of microaggressions and systemic barriers that deaf individuals face daily. For hearing visitors, reading these scenarios soon became unsettling—a poignant but sometimes shame-inducing experience.

When I spoke with the artist via her American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, Beth Staehle, last March, Kim told me that sound politics operates even within the Deaf community itself. “Those who have good speech usually have more privilege, because they speak, and that’s what society wants people to do,” Kim explained. “And then I’m on the opposite side of the spectrum. I don’t lip-read, I don’t use my voice, I’m dependent on sign language to communicate.”

Kim’s work reveals how an ability to interact with hearing culture confers advantage. It also invites broader conversations about accent bias, voice modulation, and designating certain speech forms as “acceptable” or “intelligent” in public discourse.

The Deaf Community’s Ongoing Fight for Access

Since childhood, Kim has understood that she would never have enough and would always need to ask for more: more space, more access, more acknowledgment. Her work doesn’t just point out what is missing, it demands that the gaps be filled—laying claim to what should have been available from the start.

One of Kim’s earliest realizations about unequal access came when she was in a mainstream public school that included a Deaf program. A Deaf friend of hers, praised for his speech skills, transferred to a prestigious oral school for Deaf children where spoken language was emphasized over signing. During a visit there, Kim was struck by the abundance of art supplies—materials she had never encountered at her own school. She eagerly began painting, until a teacher complained that she was using too much. That small reprimand left a lasting impression. It wasn’t just about a limited resource—it was a lesson in how access is conditional, often tied to the types of institutions you’re allowed into, and which people society deems deserving.

“My journey has been shaped by access—or by my decision to go forward knowing access wouldn’t be there,” she said. “My whole life, I’ve seen half-assed solutions and half-assed resource provisions for someone like me.” She recalls being told many times throughout her life: “We don’t have enough paper” or “You can’t go to this lecture because there isn’t an interpreter.” These constant checks shaped her relationship with institutions—she learned early on that what she was given was rarely enough, and that she had to push for more.

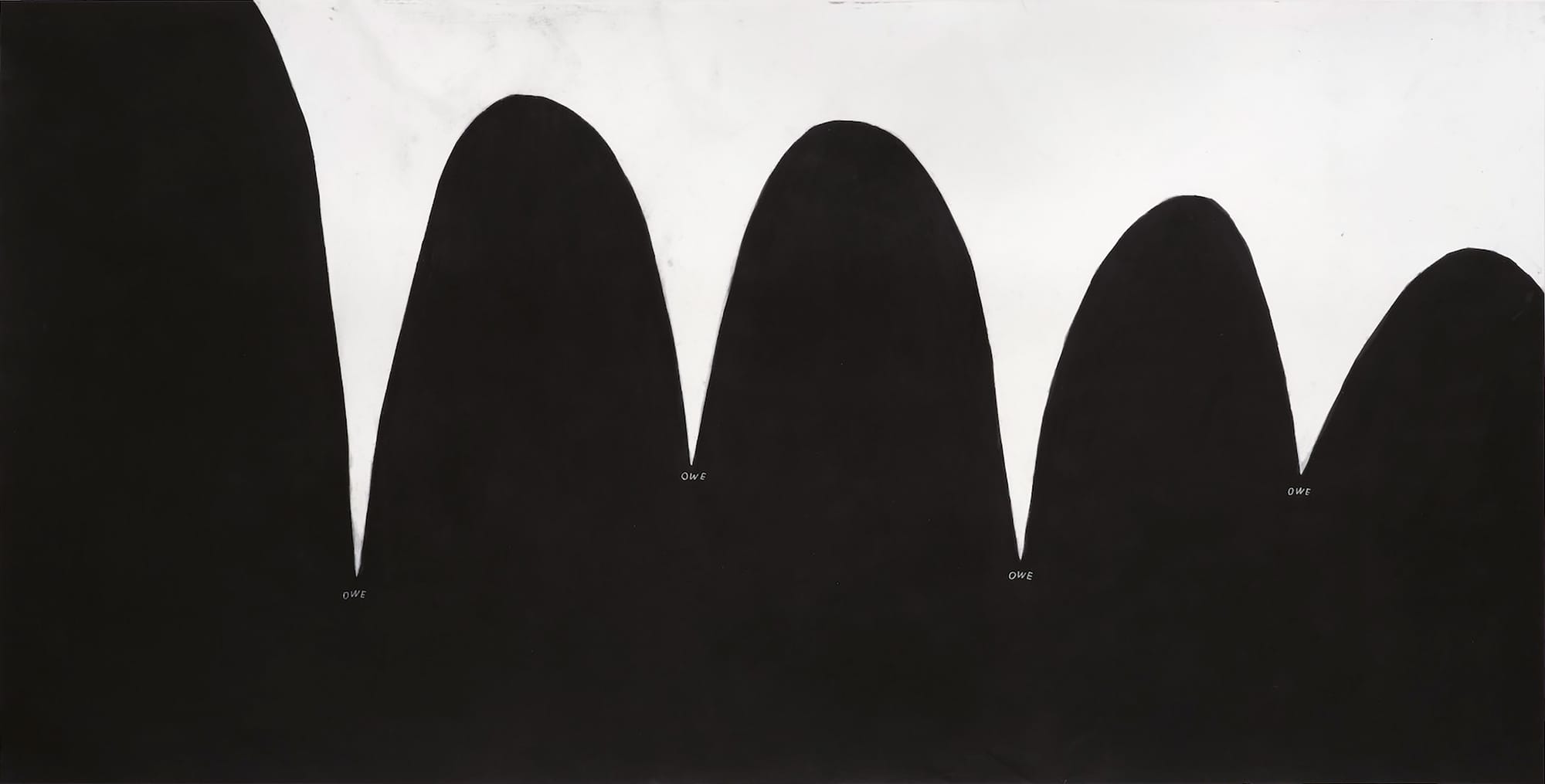

This instinct to claim space is manifest in Kim’s artistic practice. The monumental scale of Prolonged Echo (2023), drawn directly on an entire wall of the Whitney’s third-floor gallery, is a testament to the artist’s refusal to be denied. At first glance, the black arcs sweeping across the white expanse resemble waves or reverberations, but they are actually derived from the ASL sign for “echo,” which involves tapping the fingertips of one hand onto the palm of the other, with the receiving palm held vertically. The tapping hand then moves outward in a smooth, curving motion, much like the shape of the arcs depicted in the mural. This act of repetition, of a sign traveling beyond its source, mirrors how communication in the deaf community is shaped by delay. The arcs in the piece are not entirely black; white patches peek through, disrupting the flow. This unevenness evokes something incomplete, interrupted—an apt metaphor for how deaf individuals often experience speech-driven interactions, where access is not seamless but filled with gaps.