Shows

“To Save and to Destroy” at BANK NYC

To Save and to Destroy

BANK NYC

New York

Jul 10–Aug 13, 2025

History, like memory, is a reluctant confidant. It withholds more than it reveals, especially for those of us who shuttle between realms—be it cultures, continents, or genders. “To Save and to Destroy,” an exhibition at BANK NYC curated by Qingyuan Deng, investigated this quandary. Taking its title from South Vietnamese-born American novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen’s essay collection, this group show compelled us to examine not what history tells us, but what it forgets.

Amiko Li’s too quiet to hear (2023) embarks on this inquiry through a video of a spoken word performance. Li, an interdisciplinary artist born in Shanghai and now based in New York, works across photography, performance, and film to explore miscommunication and the quiet anxieties embedded in everyday life. Drifting from stories between childhood pen-pals to scam calls in Mandarin to fleeting moments of tenderness from a past romance, too quiet to hear meanders in tone as well as content, with the register of Li’s voice shifting from the measured gravitas of a newscast to the soft coo of a lullaby. Li is not interested in being “loud”; instead, he invites the viewer to lean in.

A bilingual upbringing can engender a heightened awareness toward silence and attunement, for in the passageway between two languages, one code-switches, stumbles, and even nurtures stories that fail to be translated. Li’s work doesn’t try to fill the gaps between languages—it dwells in them. For diasporic communities so often pressured to “speak up,” Li’s piece offers a radical, alternative mode of expression—one that is not mute, but intentional in its ellipses; not invisible, but firm in its refusal to conform to dominant modes of visibility. “If you come close enough, you will eventually hear me,” Li says in the performance.

The emphasis on introspective contemplation was echoed in Leon Zhan’s Melody of the Woods (2025), a painting depicting two stone lions nestled in a dusky, forested landscape—not as gatekeepers, but as witnesses. The lions sit low to the ground, partially obscured by boulders and tree trunks, the contours of their rust-colored bodies blurred by diaphanous layers of mist. In another painting, Winter Evening (2025), one solitary lion, facing away from the viewer, appears in the lower left corner. Flanked by tall, bare trees, the animal is barely visible, camouflaged into a wintry, snow-covered expanse.

Unlike the fierce, symmetrical duos seen in Chinese palaces and temples, Zhan’s lions are pensive and isolated. Born in Melbourne and now based in New York, Zhan views his lion paintings as self-portraits. The beasts recur as symbolic figures that evoke solitude, their turned backs and softened outlines suggesting both yearning and resignation. These are not lions that defend, but ones that retreat and endure, less concerned with guarding territory than with holding space for remembrance.

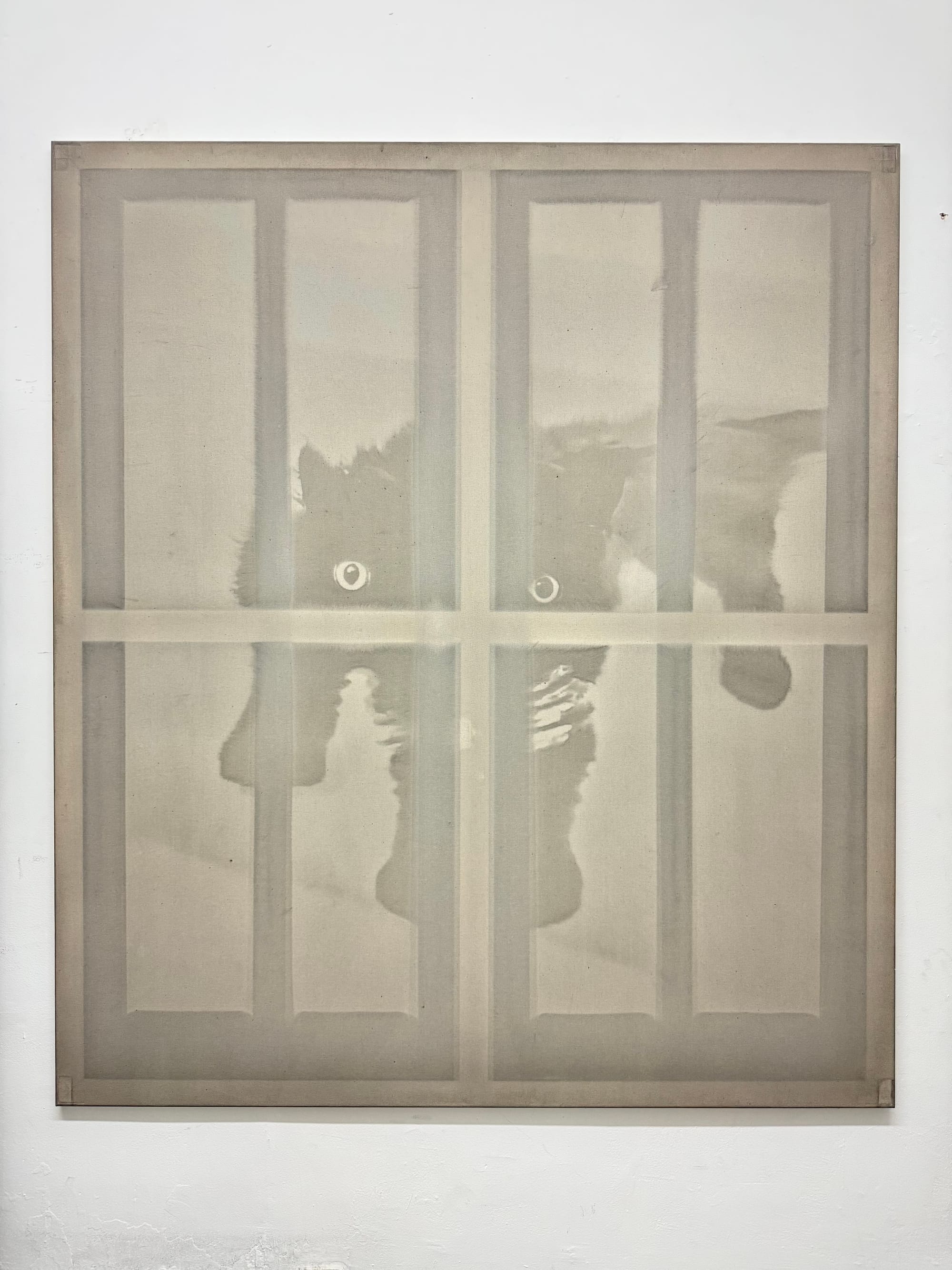

Contrasting with Zhan’s and Li’s meditative accounts, Ren Light Pan’s ink works startle with their innovative rifts between tradition and reimagination. In Cat in Water (2025), black ink bleeds across the canvas in gradients, defying the control and precision associated with Chinese brushwork. A transgender Chinese American artist based in New York, Pan was initially trained in oil painting, photography, and filmmaking, only turning to ink during a period of depression. Seeking not mastery but release, her process blends traditional Chinese techniques with contemporary modes, including exposing her inked canvases to controlled infrared beams, which alter the absorption and drying patterns of her pigments and create tonal shifts only visible under infrared light. By introducing new directions for Chinese ink, Pan’s work becomes an act of transformation and revitalization.

Diane Severin Nguyen’s photographs interrogate history not through direct representation, but by utilizing what the artist describes as “material transfiguration”—a process in which everyday objects are reconfigured into unconventional forms. In An era where war became a memory (2018), a peeled lychee glistens under harsh light, encircled by translucent shards resembling fingernail clippings. At first glance, the image appears abstract, but the materials—bodily, edible, domestic—provoke recognition. By pushing these objects to the edge of legibility, Nguyen destabilizes both semiotic expectations and the act of remembering itself. Her photographs do not recall specific narratives of war or diaspora, but instead, subtly posit how memories can be distorted and recontextualized. In doing so, she frames history not as something that is simply regurgitated, but continually refashioned.

These four artists collectively characterize history as fractured, sensory, and deeply personal. And yet, they only represent a fraction of the voices in the show, which comprises 15 artists working across mediums to interrogate the porous boundaries between memory and myth, fact, and invention. What emerges is not a singular truth, but an impulse shared by the group: to carry what haunts us, to remake what we inherit, and to communicate on our own terms.

Xintian Tina Wang is president of the New York chapter of the Asian American Journalist Association in Washington, DC. Her work appears regularly in news and culture publications such as Time, Elle, The Brooklyn Rail, ARTNews, and The Observer.