Shows

Tiffany Jaeyeon Shin’s “Universal Skin Salvation”

American pop singer Katy Perry made headlines in 2012 by proclaiming her “love” for Japanese people on Jimmy Kimmel Live, going so far as to say, “I’m so obsessed I want to skin you and wear you like Versace.” A year later, Perry again found herself accused of fetishizing Japanese women in her “geisha-style” performance at the 2013 American Music Awards, where she donned not only a sexed-up version of a kimono but also makeup that whitened her face. In her forthcoming book Ornamentalism (2019), scholar Anne Anlin Cheng points to the long history of portraying the Asian female body as “an inherently aesthetic object” and “one constructed through fabrics, ornaments, and ‘skins’ that never enjoyed the fantasy of organicity.”

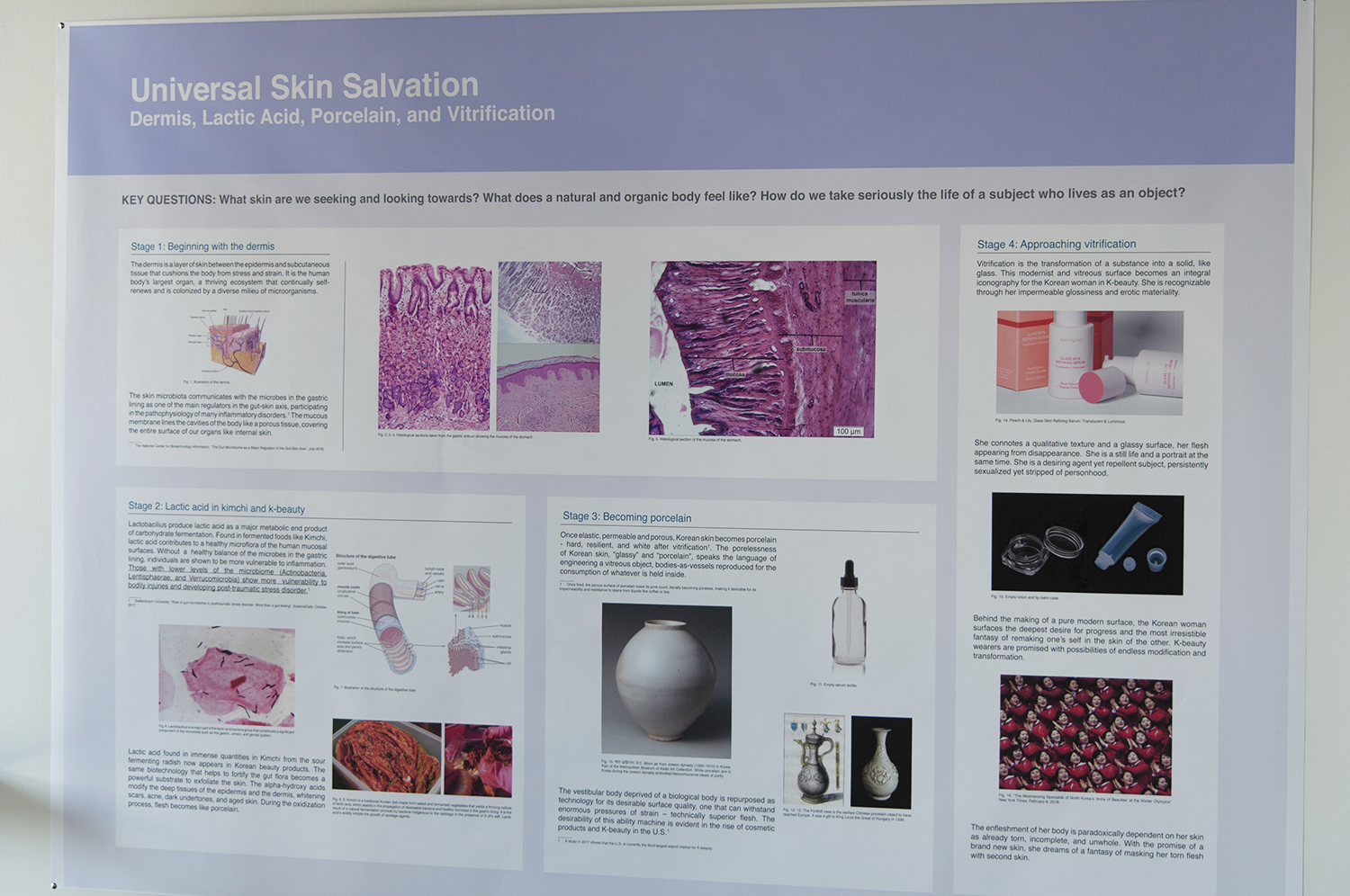

Korean-American artist Tiffany Jaeyeon Shin contemplated the permeable boundary between the organic and inorganic nature of flesh in her exhibition “Universal Skin Salvation” (all works 2018), at the Knockdown Center in Queens, New York. Transforming the gallery into a space resembling a makeshift, DIY spa, Shin explored the concept of skin as an aesthetic by reproducing many facets that define the K-beauty industry. A printed poster details some of the substances and processes essential to Korean skincare products. Most significantly, lactic acid—a bacterial compound found in sour milk and fermented foods like kimchi, as well as in our own bodies—serves as the basis for “lactification” to make the skin appear milky white.

Nearby, home-brewed lactic acid at various stages of fermentation sat in containers, one revealing what looked like cottage cheese. In the center of the room, a full-size sauna constructed out of PVC pipes and vinyl was open to visitors who could step inside and quench their skin with a mist of lactic acid and water released through a humidifier. The majority of guests hovered around a retail-ready display of custom lactic-acid formula products. They eagerly sampled the unmarked bottles, jars and tubes, testing the serums, cream and lotions on their skin. Shin recalled seeing concert-goers attending an unrelated performance by the Korean-American musician Yaeji, which took place the evening prior in the same venue, similarly flock to the sample station, perhaps unaware or indifferent to the fact that the items being exhibited were not actually promotional.

Shin’s work draws direct connection between skin-lightening products to a cliché expression about highly sought-after “porcelain skin.” In this way, she harkens back to Cheng’s argument: “Asiatic femininity is, above all, a style. As such, it claims specificity but lends itself to transferability.” Just as porcelain itself became a coveted commodity exported from China to Europe via the Silk Road, the global consumer lust for a particular kind of shiny, gleaming complexion is, for Shin, a modern-day equivalent. As the poster lays outs, the stage following lactification is vitrification—the transformation into glass. “This modernist and vitreous surface becomes an integral iconography for the Korean woman in K-beauty,” Shin writes. “She is recognizable through her impermeable glossiness and erotic materiality.” Reinforcing the glassy aesthetic, slick photographs of her homemade skincare line hang on the wall like adverts any social-media user might normally scroll past on their phone screens.

The same imagery can be seen in the video entitled 5 Step Skin Care, which takes its name from the multi-step regimen (often consisting of as many as ten steps) commonly boasted about on beauty sites. Paired with close-ups of Shin’s own dewy skin modeling her products, the subtitles relay a poem that goes beyond cosmetics and touches upon the subjectivity of the often racialized and sexualized Korean woman. It begins, “To want desire, to be desired, and to be dispossessed are one thing . . . a subject emerges from and through the fetish.” Encased in a porous and pore-less exterior, her body is a vessel containing forgotten histories and unseen traumas, which Shin intimates on a personal level, stating, “I am now who I am from the leaks of vulnerabilities that animate the marks of war, a war that I cannot remember and a war that remains in the vast consciousness forgotten.” Thus, “Universal Skin Salvation” links the legacy of the Korean War to the Korean woman, whose flesh then functions as a site where such inherited trauma can be made over and rehabilitated. Through the aspirational quality promoted by K-beauty, she finds herself reduced to a luxurious, fashionable skin that can be worn.

Mimi Wong is a New York desk editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

Tiffany Jaeyeon Shin’s “Universal Skin Salvation” is on view at the Knockdown Center, New York, until December 16, 2018.