Shows

“Threads of Kinship” at KADIST Paris

Threads of Kinship

KADIST Paris

Oct 11, 2025–Jan 10, 2026

Hair, thread, and quiet acts of refusal anchored the conceptual weave of “Threads of Kinship,” presented by KADIST Paris in collaboration with He Art Museum in Guangdong. Eschewing a grand narrative, the exhibition opened with a small but decisive rupture: one embodied by the Self-Comb Sisters of early-20th-century Guangdong—women who rejected marriage for communal sisterhood sustained through silk production before its decline pushed many into domestic work in Southeast Asia. Dismissed as eccentric, the Sisters split the seams of Confucian order and recast kinship as chosen rather than imposed. From this tear, the exhibition traced resonances across hair, textile, labor, superstition, and migration, linking delicate materials and gestures to broader structures of belonging.

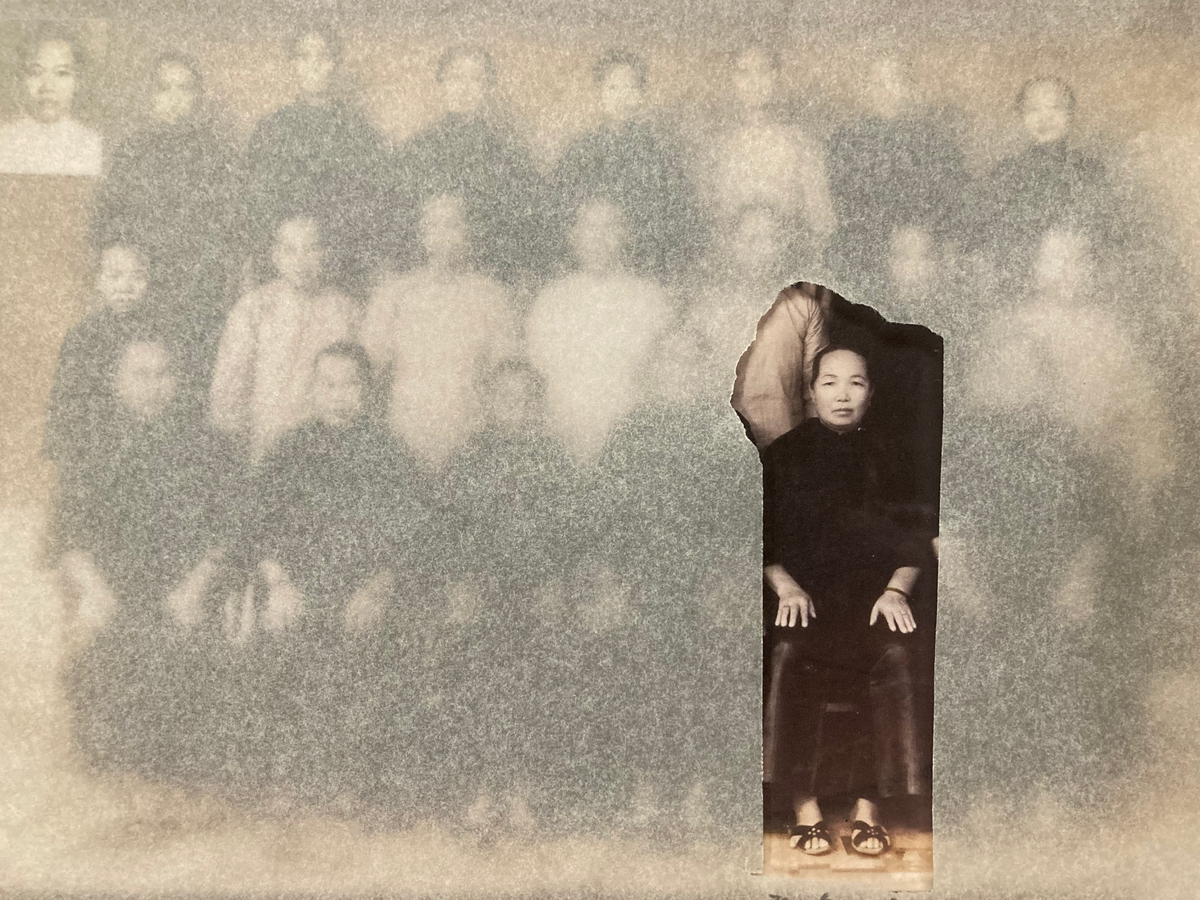

Chen Jialu’s research-driven installation formed the show’s backbone. Drawing on fragmented archives and oral histories, she reconstructed the Sisters’ autonomy through the very frameworks that once hemmed them in. A single braided bun—once signaling a vow to remain unmarried—hung in a net, its stillness activated by recorded voices playing through small speakers concealed within the hair. The multipart installation also incorporated photographs, maps, embroidery, and video to evoke the communal Gupouk (“spinster houses”) where these women lived and worked. A suspended textile, the Gupoyu, named after a hardy yet toxic plant, was a quiet emblem of endurance: sometimes resistance isn’t loud; it accumulates—life lived differently becoming its own radical act.

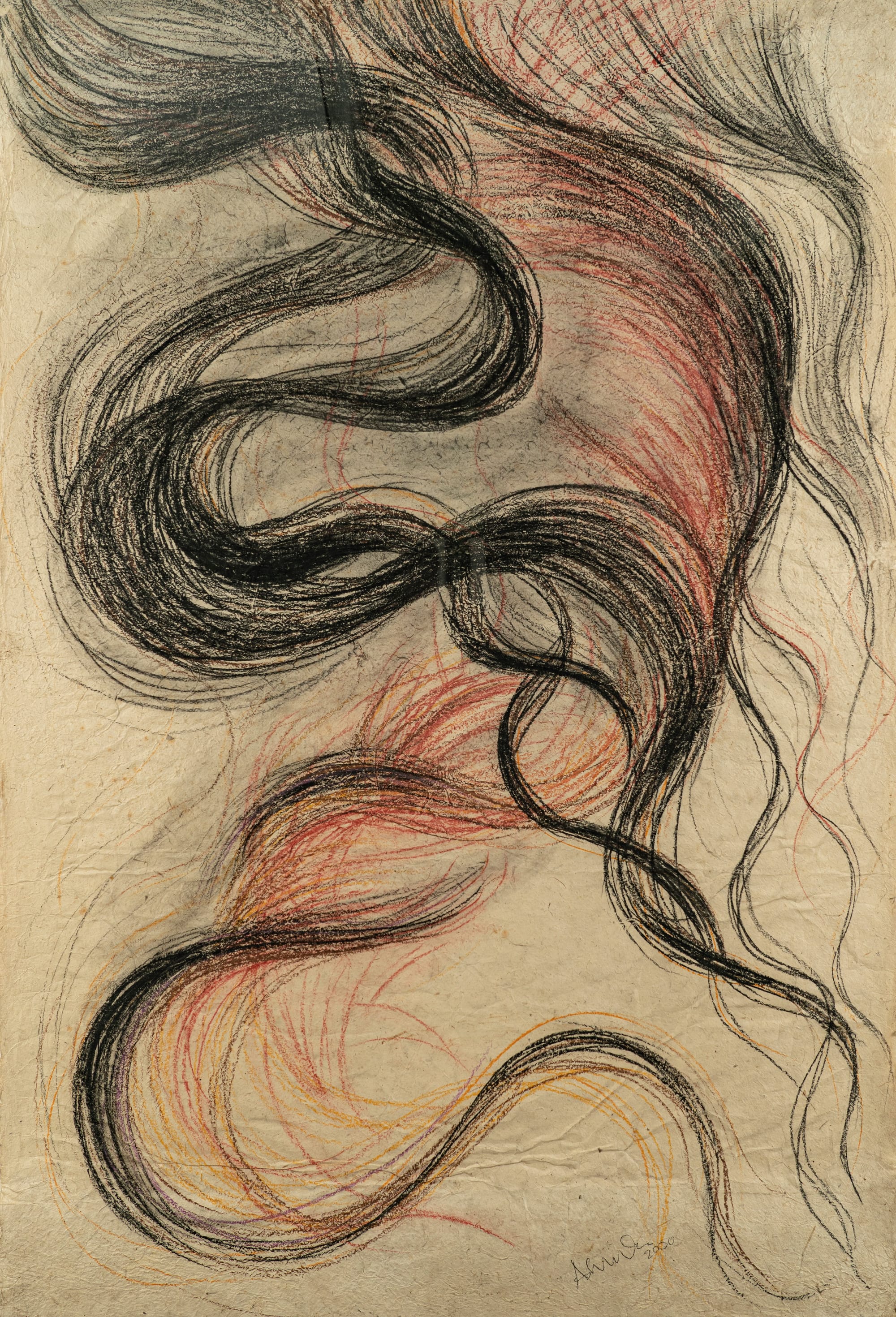

Installation view of “Threads of Kinship” at KADIST Paris, 2025–26. Photo by Vinciane Lebrun of Voyez-Vous (left); and ASHMINA RANJIT’s Hair Warp – Travel Through Strand of Universe, 8 (right), 2020. Courtesy KADIST Paris.

Hair emerged as a recurring motif. In Ashmina Ranjit’s drawing, Hair Warp – Travel Through Strand of Universe, 8 (2020), black and red strands on lokta paper recast hair—a potent Hindu symbol—as a site of feminine agency, with the color red—long tied to marriage and barred to widows—reclaimed as power. The slippage between hair and thread—parallel carriers of lineage and memory—reappeared in Tarik Kiswanson’s Passing (2020), an X-ray overlay of an 18th-century Jordanian dress and a contemporary tracksuit. Hand-stitched red threads pierce the image and drift beyond its surface, extending its meditation on inheritance, migration, and the fragile seams that bind generations.

If hair can empower, it can also haunt. Across cultures, women’s hair has long been regulated—braided, veiled, contained. Let it fall, and she becomes unruly, even dangerous. The pontianak, a vengeful Malay spirit with cascading tresses, distills these anxieties into a figure long feared especially by men. This specter is evoked in Yee I-Lann’s photographic print, where women dressed in contemporary clothing stand among banana trees, their faces obscured by long, loose hair. Harnessed as a symbol of resistance and regeneration, their wild locks push back against narrow ideals of femininity, recalling the suppressed legacy of Gerwani, Indonesia’s leftist women’s movement dismantled under Suharto.

These fantasies of supernatural female danger also bleed into everyday superstition. Sawangwongse Yawnghwe’s 22022021, Yawnghwe Office in Exile (2021) makes this palpable. Near the entrance, Burmese women’s longyis hung across a clothesline that visitors had to duck beneath, echoing a protest tactic after the 2021 coup. Because such garments were believed to sap a man’s hpone—his spiritual authority—soldiers were forced to remove each line before advancing, turning laundry into a barricade. Sourced along the Thai-Burma border, the longyis bore marks of displacement, their coup dates rendered in crushed shell pigment. Tender yet defiant, they linked personal exile to collective struggle.

Domestic labor—feminized and often invisible—formed yet another strand of the exhibition. In Ma Qiusha’s wall-based assemblage Wonderland–Eros No. 3 (2020), cement shards from an abandoned ’90s amusement park outside Beijing are wrapped in reclaimed stockings, some patched with nail polish, transforming gestures of repair into intimate records of care. Hu Yinping’s suspended installation Potatoes Grow on Trees (2025), co-created with women from her rural hometown in Sichuan, turns crocheted potatoes into tactile monuments to agricultural knowledge. Both works insist that survival rests not on grand acts but on maintenance, mutual aid, and daily tending.

Risham Syed’s installation Ali Trade Center Series IV (with Buddleia) (2022) unfurled the exhibition’s widest arc, with a quilt made from her late mother’s Chinese silk brocade—once brought into Pakistan along pilgrimage routes—serving as both armature and ground. Flanked by two vintage lamps, the fabric tableau gathers vintage maps, colonial interiors, a plume of smoke, and a wandering Buddleia stem around Lahore’s Ali Trade Center. Folding affective memory into geopolitical currents, the work traces how a single textile carries women’s labor, trade, and empire across time.

Ultimately, “Threads of Kinship” revealed how women stitch continuity from rupture, resistance from routine, and belonging from the fragile materials of everyday. Here, kinship was not inherited but practiced—woven, unpicked, and remade across borders, systems, and generations.

Yvonne Wang is an art writer and ArtAsiaPacific’s Singapore desk editor.