Shows

“Suzann Victor: A Thousand Histories” at Gajah Gallery Singapore

Presented by Gajah Gallery Singapore

Suzann Victor: A Thousand Histories

Gajah Gallery Singapore

August 2—September 7

In the currents of contemporary art of Southeast Asia, few practices resonate with the conceptual depth and formal precision of Sydney-based Singaporean artist Suzann Victor’s. Her critical engagement with feminist interrogations of bodily norms, forms of disembodiment, perceptions of the abject, and the aftermath of colonialism led to work that viscerally embodies their politics rather than illustrates them. Her latest solo exhibition at Gajah Gallery Singapore, A Thousand Histories, attests to nearly three decades of rigorous experimentation to expand the perceptual and political abilities of the lens as one of the key artistic media in Victor's practice.

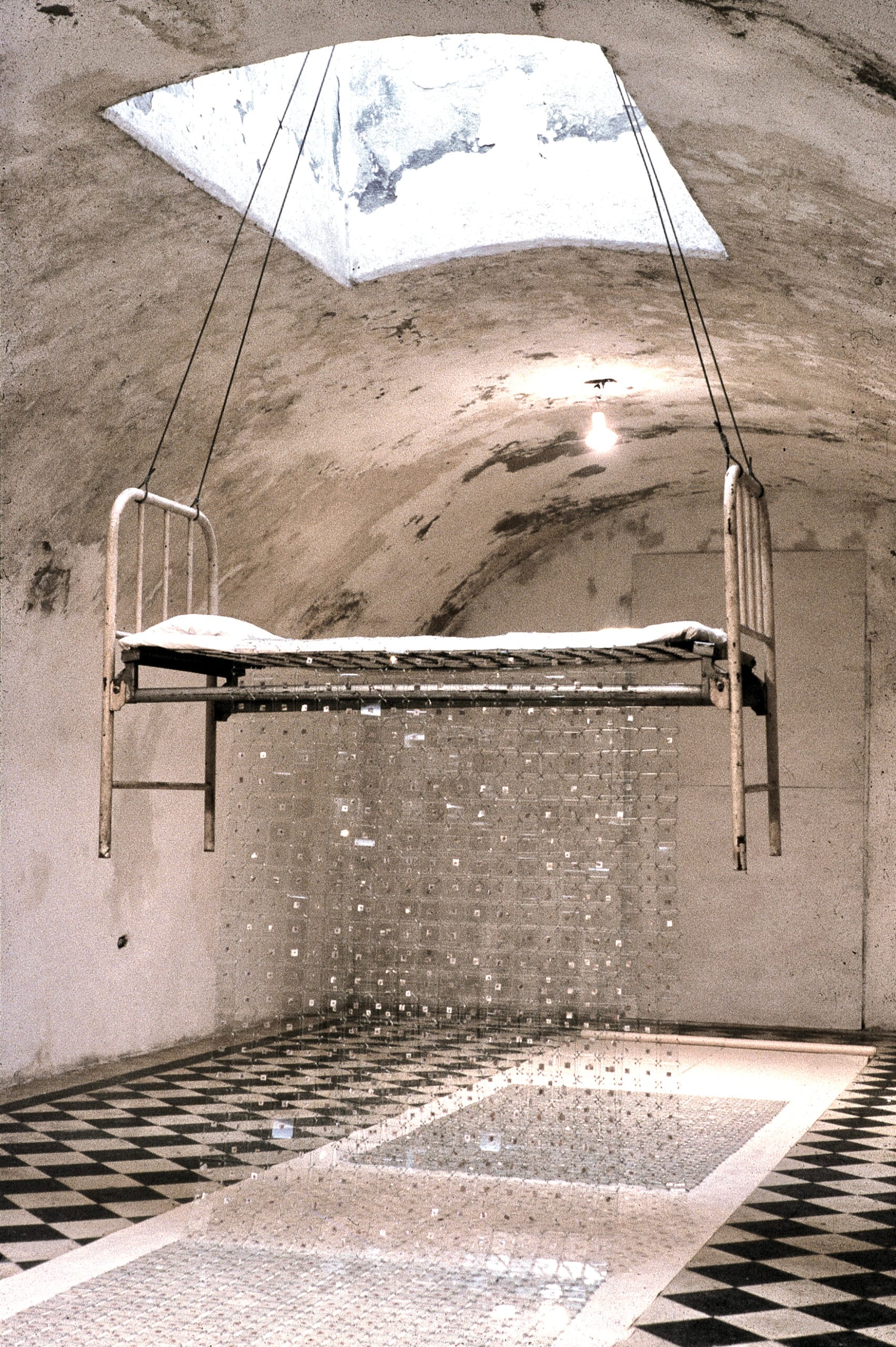

First deployed at the 6th Havana Biennale in the work Third World Extra Virgin Dreams (1997), 3,000 lens-glass pieces were hand-stitched into a 10-metre glass quilt trailing from a suspended military bed, each sealed with a drop of human blood extracted from the artist and her Cuban host. With the scant resources of a single light bulb due to the US embargo, Victor used the lenses to amplify light in the dim vault. Cascading onto the floor like a radiant river redistributing scintillating sunlight throughout the centuries-old space, it exuded a material and phenomenological ambiguity between fragility and strength, visibility and invisibility, ascent or descent, intrusion or expulsion out of the architectural orifice—the skylight above.

The inventiveness with which the physiological and perceptual qualities of Fresnel lenses are activated would become a defining feature in Victor’s later works, e.g. Bloodline of Peace (2015)—a 40-metre lens quilt comprising 11,520 lens units, commissioned by the Singapore Art Museum for the city-state’s 50th year of independence.

Lenses were further developed into viewing devices of architectural scale in her Lens-Sculpture series, which occasioned an intimate communion between time and place—the slow reveal of the immediate environment through the lenses, while being profoundly aware of the present moment. This occurred outdoors in A Thousand Skies (2017), sited at the thousand-year-old Joten-ji Temple and Rising Sun (2018) at the ancient ruins of Fukuoka Castle that arose out of a special artist residency at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, while indoors, See Like a Heretic (2018) was developed in collaboration with Gajah Gallery’s Yogya Art Lab.

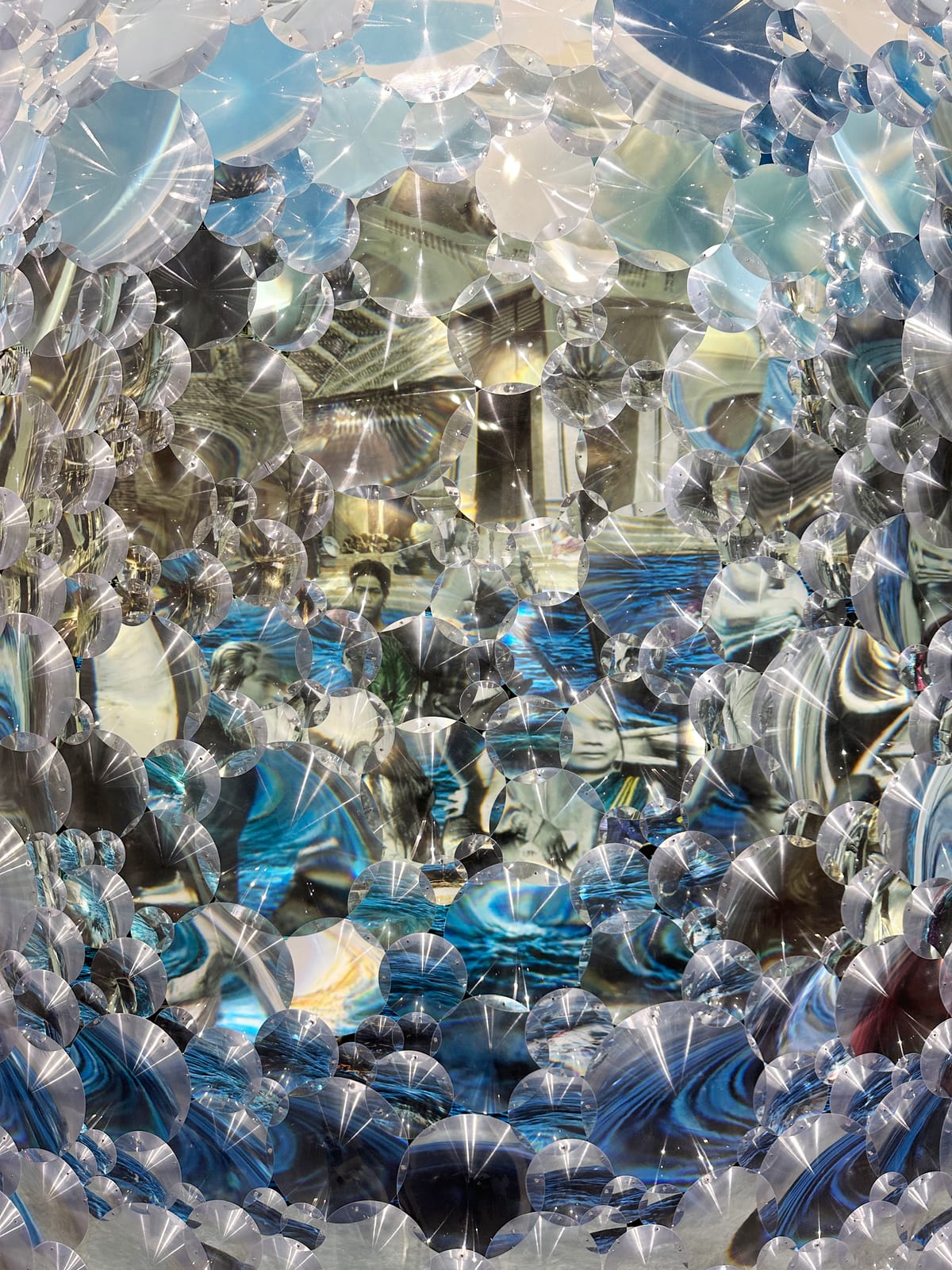

The Lens Paintings series marked a new development in Victor’s treatment of Fresnel lenses as a means of interfacing with colonial imagery and private archives. Fractured and obscuring, yet bringing the pictorial narrative into focus one micro-view at a time, the lens paintings induced the shifting and angling moves of the “kinetic” viewer upon whom any observation of the artwork is contingent. Never at once, could the entirety of the rendered subjects beneath the lenses be seen clearly in works such as She’s Dearer Than You Think (2020). The painting’s source material was drawn from the personal archives of a Malaysian woman who was coerced into sexual slavery as a comfort woman in World War II, and revealed as the grandmother of Victor’s friend.

For Unequal Innocence (2020), Victor drew from ethnographic images of women across Asia found in postcards of the 1900s, replete with their sombre, defiant gazes. Fissures, laser-burned into some lenses provided direct glimpses into slivers of minutiae below. Drawn from images of veins and riverine systems, they confronted viewers like wounds deliberately cauterised to remain open—offering unadulterated insight. The cumulative effect of the painted canvases and Fresnel lens screens called into question the obfuscation and occlusion of women and their roles in history—marking the reveal of their stories as lacerations that may never find closure.

River of Returning Gazes (2022) and A Patchwork Tells a Thousand Histories (2023) were similarly invested in rematerialising the moments of colonial encounter by liberating (retrospectively) the humanity of the photographed subjects that have been reduced and captured in these dehumanising ethnographic portrayals. The artwork became a site to speak from rather than to speak about and around those depicted. At such a location, a reworked Singapore River also offered a panoramic “humanscape” proliferating with the complex and rich but obscured migrant histories that founded the postcolonial city-state.

In her latest exhibition, the gallery space is transformed into a cinematic arena that physiologically and perceptually impede the acts of hierarchical looking and representation. Dominated by three monumental kinetic-lanterns and a 6-metre suspended wall comprising image-narratives behind thousands of lenses, these sculptures evoke the architectural and surveillance technology of the panopticon – only to radically subvert them. A seamless 10-metre backlit image rotates behind the lenses, but the lenses display divergent directions of both clockwise and anti-clockwise trajectories at once.

In the words of writer Anca Rujoiu, “As in Victor’s other kinetic sculptures, the unmooring perception stems not from engineering complexity but from the quiet force of fundamental optical physics.

No single image can be fully seen, consumed, or possessed. There is no fixed vantage point. There is no totalising gaze. The image remains in perpetual motion; it refuses to yield clarity or closure. What does a lens do? It unfolds a thousand histories.”

A Thousand Histories opens at Gajah Gallery Singapore on 2 August and runs through 7 September 2025.