Shows

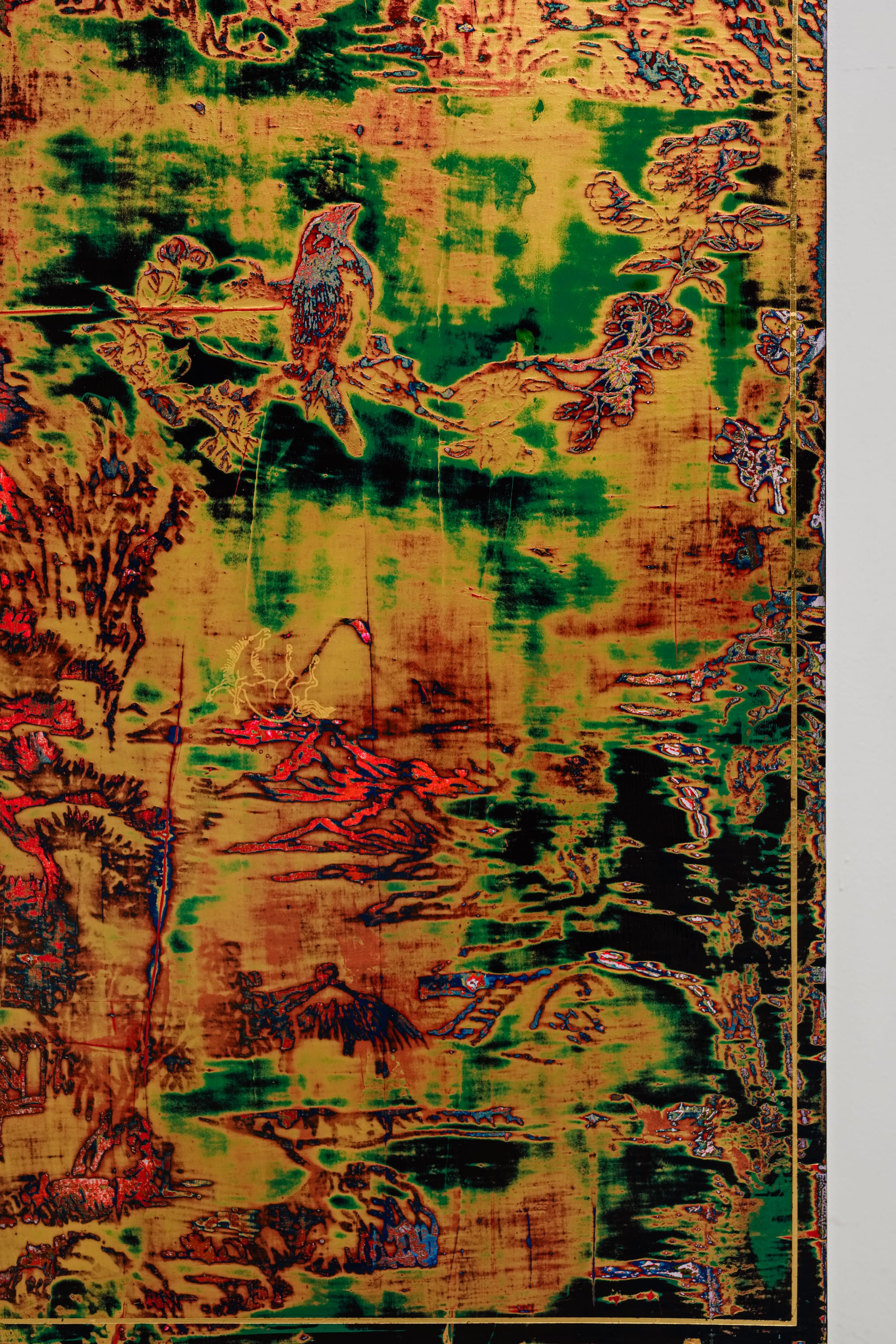

Su Meng-Hung, Desolate Landscape on the Golden Screens

Essay by Barbara Pollack

Su Meng-Hung, Desolate Landscape on the Golden Screens

Presented by Tina Keng Gallery

Art Basel, Unlimited Sector Booth U55

June 16—June 22, 2025

Contemporary artist Su Meng-Hung explores cross-cultural conversations with his magnificent installation, Desolate Landscape on the Golden Screens. These sumptuous works—part painting, part sculpture—incorporate Chinoiserie, lacquerware, silk screens, and Andy Warhol. Taken together, they create a maze that steers viewers through an investigation of the art histories of China, Taiwan and global contemporary art.

It is not surprising that Su Meng-Hung has studied these histories in depth. Born in Taiwan in 1976 to a family that has resided there for generations, Su studied art at National Changhua University of Education and worked for five years as a high school teacher before taking a loan to attend Goldsmiths College in London at the age of 30. He received his PhD from the Tainan National University of the Arts. Throughout his career, Su Meng-Hung has uncovered new layers to the East-meets-West metaphor applied to too many Asian artists. He is particularly concerned with terms like “Oriental,” “authenticity,” and “exotic” that underlie western expectations, but also have been internalized by artists in acts of self-orientalization.

Every aspect of Su’s art-making practice incorporates historic references and cultural idioms. From a distance, the screens appear to have the marbled surface of mother-of-pearl inlay. Up close, they reveal well-known patterns silk-screened onto canvas covered wood planks. He then sands the surface until it is as smooth and reflective as a mirror, an effective imitation of lacquer ware.

Su appropriates the illustrations from three well-known books—The Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, Dream of the Red Chamber, and The Golden Lotus–combining the innocent trope of bird-and-flower painting with the suggestive couplings of classic erotica. Su is fascinated by the way his chosen imagery, once revered, is now recycled into kitsch. For example, the bird-and-flower motif, found on paintings in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan, were once incorporated into Chinoiserie produced for western consumers and are now best known in Taiwan as decorations for wedding ceremonies and shop windows. This two-sided popularity fascinates the artist.

In fact, Su Meng-Hung’s first engagement of bird-and-flower paintings was the work of Giuseppe Castiglione, an 18th century Italian Jesuit brother and missionary in China, where he served as an artist at the imperial court of three Qing emperors. Castiglione is credited with introducing the concept of perspective to the iconography of ink-and-wash paintings. The fact that cross-pollination between Asian and western cultures has been taking place for centuries inspired the young Taiwanese artist to consider what he can add to this tradition. It is also a fact that Su did not encounter screens growing up in Taiwan, no one in his workers’ family would have one in their home. He first saw one in a Coco Chanel’s Coromandel lacquer-ware screens through a photograph of her apartment in Paris. Once again, a product of design intended for a western audience, awakened Su to the potential beauty of “inauthentic” artworks.

While stunningly beautiful, this art practice is also highly conceptual, raising the question, “What is authentic Taiwanese art?” The Taipei National Palace Museum displays the premiere works of a Chinese culture brought by the Kuomintang government. The colonial legacies of Japan, Spain, and the Netherlands are also influential. There’s also the indigenous cultures preceding them. “All together they form a multifaceted cultural archive that Taiwanese artists draw upon to redefine themselves,” according to Su Meng-Hung’s writings. He also adds in the legacy of Chinoisere (produced for trade with foreigners) and modern ideas of contemporary art introduced to Taiwan since WWIl.

Su captures these layers of history in his process itself, but also is aware of his own engagement with “self-exoticism,” manipulating materials to raise the intrigue and mystery associated with Asian art. He likes to point out that he himself is not painting at all, merely scraping colors through silkscreens without using a brush. His labor-intensive process then involves sanding the surface, literally erasing layers of culture, then coating the surface and sanding again until he achieves the surface he desires. His body is literally in the work, his movements back-and-forth incorporated into the making. Su is aware that in addition to the history of the imagery, the history of craftsmanship is equally important. Combining imagery and abstraction, mass production and touch, craft and concept, this artist works for and achieves a powerful statement about the fractured nature of identity in a post-global world.

In this way, Su reimagines the traditional folding screen as both high art and commodity, literati culture and kitsch. The vibrant colors revealed beneath the ebony surface can be examined and reexamined on each viewing or can be taken in as whole from a distance. This builds to a multifaceted experience of art, akin to a multimedia environment or a spectacle achieved through digital means. Su acknowledges that people are completely “screen-obsessed” including laptops, monitors, iPhones and IMAX, without even thinking of an art encounter with multipaneled furniture or painted silkscreens. From screens to screens to screens, Su literally updates the act of viewing from early history to the present-day without missing a beat.

Do not be distracted by Su Meng-Hung’s craftsmanship when viewing these magnificent artworks, his folding screens. The works are stunning, but elevating the craft over concept only diminishes the impact and meaning, just as western viewers have exoticized Asian art for centuries. Try to open the mind to the ways that Su is deconstructing that history and at the same time, sharing with us the pressures to “self-exoticize” , to become an “Asian artist” instead of being himself. He is undeniably an international artist, presenting important insights into the way culture is produced and reproduced. Desolate Landscape on the Golden Screens is a significant contribution to this discussion and a major achievement for the artist.

Barbara Pollack is an award-winning journalist, art critic and curator, and is one of the world’s leading authorities on contemporary Chinese art.