Shows

“Saved Treasures of Gaza: 5000 Years of History” at the Institut du Monde Arabe

Saved Treasures of Gaza: 5000 Years of History

Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris

Apr 3–Dec 7, 2025

The Palestinians, living under the longest military occupation of modern times, have never had the opportunity to fully develop a national archaeological program—one that tells their own story rather than that of foreign interlopers. Under the British Mandate, early excavations in Gaza served biblical and often pseudoscientific interests that buttressed colonial claims over Palestine. Historian Meron Benvenisti has shown how the British formulated the region’s archaeological chronology around successive conquerors, a framework later modified by Israeli scholars to spotlight specifically Jewish historical periods such as the biblical, Hasmonean, Mishnaic, and Talmudic eras. Until recently, the identities and interests of Arabs, Bedouins, peasants, and villagers were scarcely considered.

“Treasures,” a compelling exhibition with a dramatic backstory, was not overly critical of such ideological biases. As its title indicated, the exhibition foregrounded something more urgent: archaeology as evidence, even heroic resistance, against ongoing cultural erasure and genocide. Its 130 artifacts were drawn from a larger corpus of 529 items from Gaza that found temporary refuge in Europe for 20 odd years. About half, owned by the Palestinian Authority, were unearthed during French-Palestinian excavations at four extraordinary sites: Tell al-Sakan, the ancient port of Anthedon, the Monastery of Saint Hilarion, and the Byzantine mosaics of Jabaliya. These items were exhibited in Paris, Arles, Lille, and Dunkirk from 2000 and traveled to the Geneva Museum of History and Art in 2007, where they were joined by around 260 works from the collection of Jawdat Khoudary, Gaza’s preeminent archaeological collector and construction mogul. The Geneva Museum had agreed to support the establishment of a permanent archaeological museum in Gaza, but after Hamas’s 2006 election and Israel’s subsequent blockade in 2007, the objects were forced to remain “in exile” in Geneva for the next 17 years.

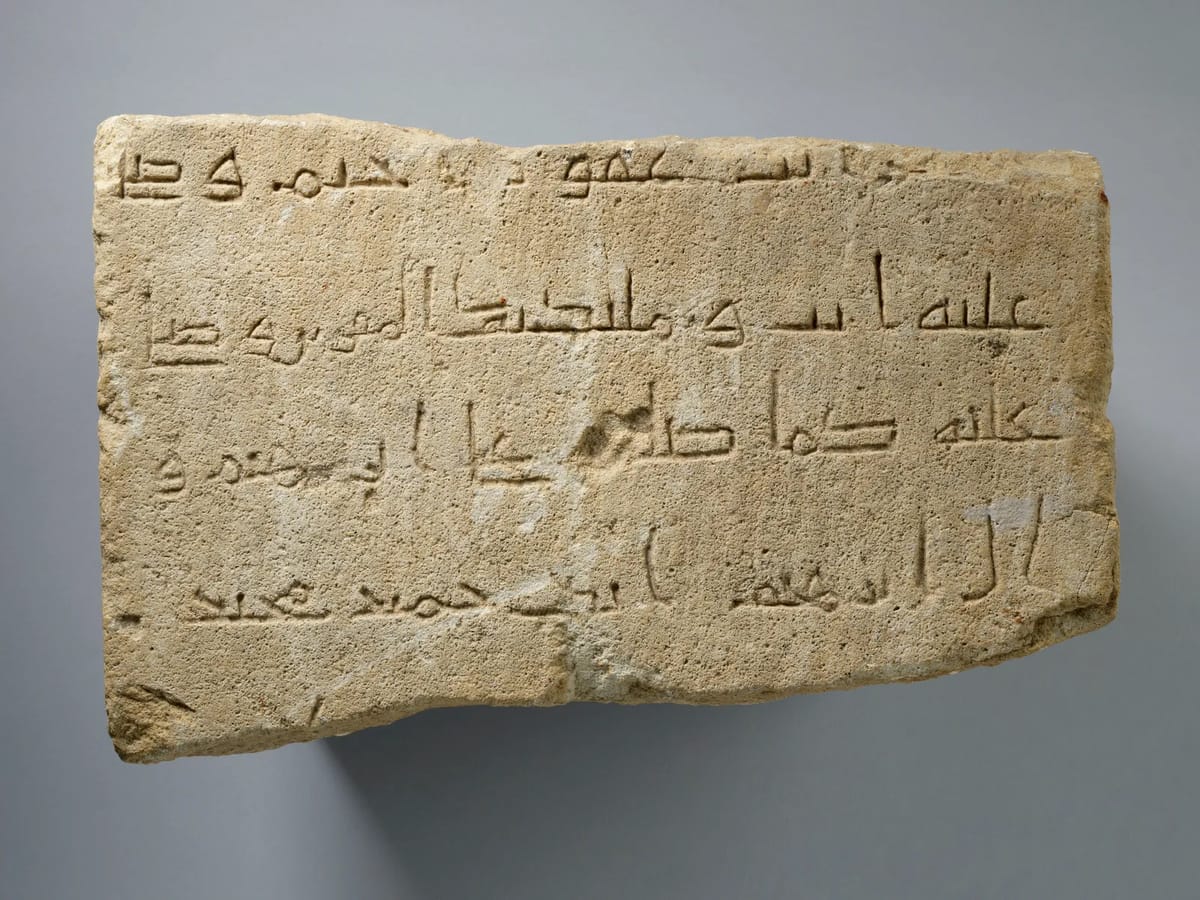

On the first floor, artifacts were grouped across overlapping historical periods and political regimes: the Bronze and Iron Ages, the Assyrian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Muslim periods, the latter encompassing the Crusades, Mamluks, and Ottoman rule. Rather than focusing on particular mediums or themes, the curators opted for a somewhat scattershot but colorful assemblage that offered a flavor of the maritime urban center’s dynamic trade, industry, culture, and everyday life. Mimesis and abstraction, two universal characteristics of early civilizations, were evident among the exhibition’s earliest works: a fist-sized, chalky limestone frog dated to the Early Bronze Age and a Late Bronze Age cowbone handle incised with a geometric pattern. The exhibition text noted that such handles may have been produced in a few workshops similar to those in the ancient city of Byblos, in modern-day Lebanon. Several items from the Roman period are not uncommon objects, yet became poetic and evocative in their pairings: three delicate bronze statues of the Greek immortals Serapis, Aphrodite, and Osiris-Antinous were juxtaposed with a modest bronze snail and mouse, as well as a cast bronze oil lamp with an ornate handle in the shape of a pouncing lion. Palm-size terracotta oil lamps feature dynamic reliefs of Cupid, a centaur, an erotic couple, and a gladiator.

Photos by Bettina Jacot Descombes (left) and Flora Bevilacqua (right). Courtesy the Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris and Architectural Digest Middle East.

Utiliarian artifacts throughout the exhibition evoked Gaza’s cosmopolitan, far-reaching connections by land and sea. A section titled “Amphorae and the wine of Gaza” brought together large and small Greek and Roman amphorae in remarkable condition. Another section, “Gaza and the sea,” presented hefty stone and marble rings, possibly used as mooring devices for boats and ships. Gaza’s rich trading history was represented in a multitude of coinage: a Phoenician-era piece featuring the Egyptian god Bes; French, Persian, and Egyptian coins from the Middle Ages; shell necklaces; and a fused hoard of 20,000 coins. One exhibition panel noted that after the emperor Hadrian’s visit to Gaza in 129 CE, he bestowed the territory with the privilege of issuing a series of five coins similar to those of the Roman Senate. A series of architectural capitals gestured to the temporal breadth of Gaza’s architectural heritage, while funerary steles registered the spans of individual lives. Together, these objects emphasized Gaza’s historical and geographical prominence as a crossroads between Asia, Africa, and the Mediterranean, defined more by constant flow than fixity.

Detail of a Byzantine mosaic of Jabaliya. Copyright J.B. Humbert. Courtesy the Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris.

The exhibition’s centerpiece was a spectacular Byzantine mosaic from Deir al-Balah (“Monastery of the Date Palm”), which depicts 15 imaginatively rendered animals, human figures, and agricultural motifs such as vine leaves and a basket overflowing with grapes. Another key work was a small, elegant marble statue, likely representing Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and pleasure, her hand resting on a miniature Hermes. Discovered by a fisherman in the sea off northern Gaza, she was, fittingly, plucked from the seafoam in an uncanny echo of Aphrodite’s origin myth.

Below, the exhibition’s second floor presented a stark archive of Israel’s recent annihilation of Gaza’s landmarks, historic monuments, and archaeological sites. Information displays soberly paired before-and-after images and site histories with wrenching statistics on cultural destruction. The Church of Saint Porphyrius, believed to be the world’s third-oldest active church, was bombed in October 2023, killing several civilians who had sought shelter from the Israeli assault. Palestine’s first mosque, the Great Omari Mosque, was severely damaged by Israeli airstrikes in December 2023. Jawdat Khoudary’s private museum Al Mat’haf, Gaza’s first archaeological museum, was burned and reportedly looted. Documenting the prewar life of these irreplaceable Gazan landmarks, the walls were lined with black-and-white photographs from the École Biblique et Archéologique Française de Jérusalem, taken in the 1920s as increasing numbers of Jews fled to Palestine to escape pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe.

Many viewers will have left “Treasures” deeply shaken by its dense material evidence that Palestine was never “a land without a people,” a Zionist claim long used to justify settler-colonialism and ethnic cleansing. Yet the exhibition was merely the tip of the proverbial iceberg: it insisted we ask whom the “treasures saved from Gaza” have been saved from, and for whom they are now being kept. For now, the works—like the Palestinians to whom they belong—remain refugees.

Chin-chin Yap is a Singaporean writer and filmmaker based in Lisbon and contributing editor for ArtAsiaPacific.