Shows

Mr.’s “People misunderstand me and the contents of my paintings . . .”

Five years after the artist’s 2013 Hong Kong debut, Perrotin brought Mr. back to the city with the solo show “People misunderstand me and the contents of my paintings. They just think they are nostalgic, cute, and look like Japanese anime. That may be true, but really, I paint daily in order to escape the devil that haunts my soul. The said devil also resides in my blood, and I cannot escape from it no matter how I wish. So I paint in resignation.”

The awkwardness of the lengthy title clearly suggested what one might expect from the show. Mr. presents himself as a stereotypical otaku, a Japanese colloquial term comparable to “geek,” especially one who is obsessed with anime, manga, and video games. As early as 2004, Japan had already used otaku as the theme of its national pavilion at the ninth Architecture Biennale in Venice, where these subcultures were significantly featured to illustrate their impact on Japanese urban development since the 1990s. Mr.’s latest show at Perrotin Hong Kong further cemented otaku culture’s place in mainstream art scenes.

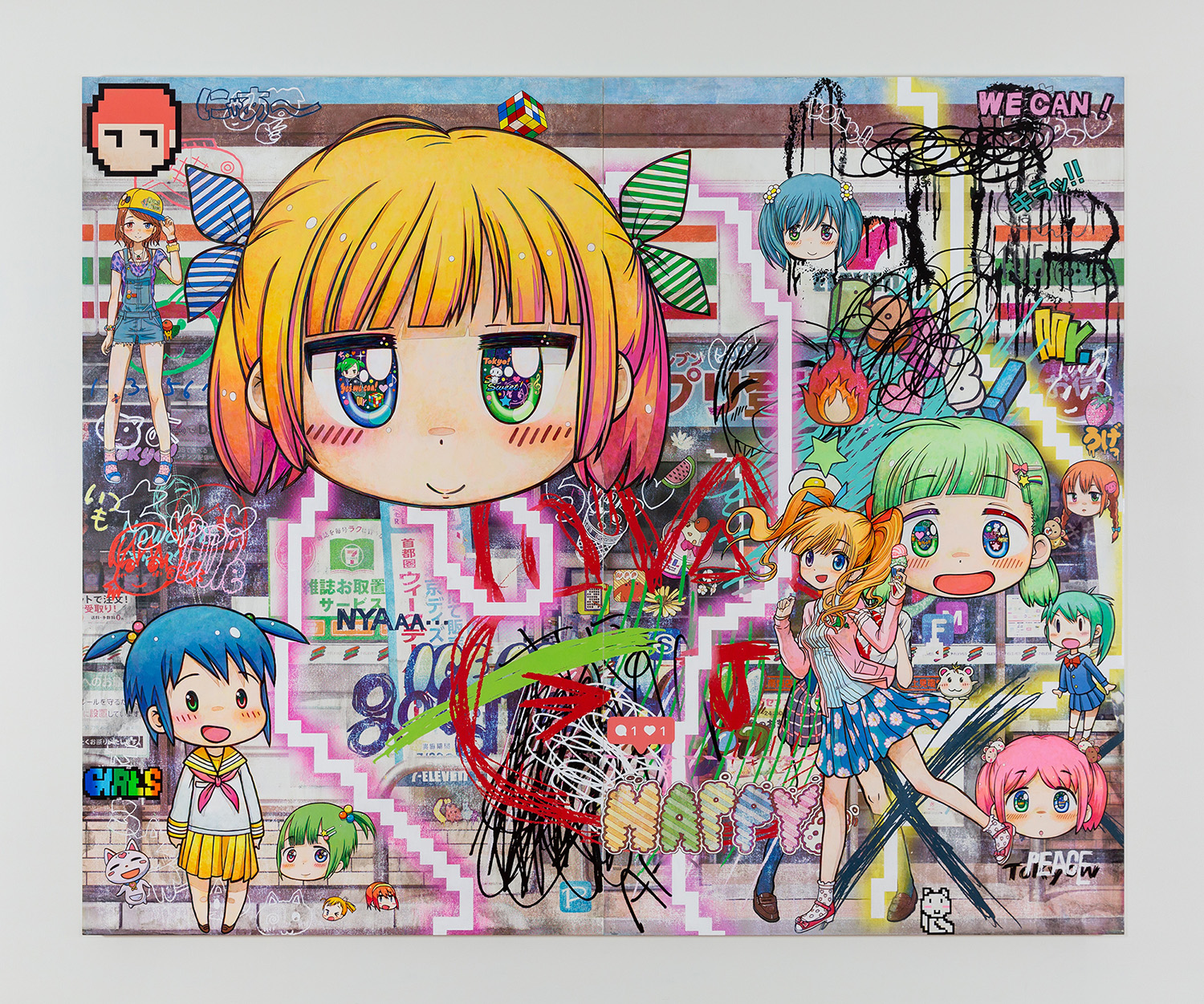

The exhibition displayed nine of Mr.’s recent works, including large-scale acrylic paintings, silkscreen prints and a toy-figurine-like sculpture, as well as earlier drawings and paintings. Considering Mr. has been a protégé of Takashi Murakami for more than 20 years, it is no surprise that their works share a “superflat” style—a reference to various flattened forms in Japanese graphic art, animation and pop culture—employing vivid colors in crammed, collagist compositions. Perfectly exemplifying this style is Untitled (2018), which occupied the central space of the gallery. Spanning nearly three meters wide, the acrylic painting is packed with comic-style figures, randomly arranged doodles, and pixelated blocks recalling antique Nintendo game consoles. Behind the dazzling assemblage of images and peppy words such as “happy” and “we can,” the viewer can identify what looks like the storefront of a 7-Eleven convenience store—a familiar sight in Japan and Hong Kong.

Two large prints stood out from the rest of the splashy paintings. Instead of the intense, vibrant coloring common in other works, these two pieces employ monochrome, recognizably Japanese street scenes (judging from the telephone poles and roofs) as their backgrounds. Viewers can still spot colorful slogans and manga-style characters, but placed in more diminished manner, occupying tiny corners of the canvas. What is overwhelming about these works, on the other hand, are ubiquitous scribbles and graffiti-style words whose meanings seem irrelevant to the cute figures, including “so fresh,” “good morning” and “depopulation” (kaso). The grayish tint in this pair of works added a melancholy atmosphere that contrasted with the cute, cheerful figures, offering a glimpse of the artist’s inner anguish, as relayed in the show’s title, as well as the wider, well-documented problem of depression among Japanese, which has risen in the wake of economic troubles, a series of devastating natural disasters, and the Fukushima nuclear accident of 2011.

Also showcased were over 80 of Mr.’s smaller works since 2010, including mini versions of his large-format paintings, pencil sketches, and even a rare self-portrait. Framed and tightly clustered into several groups, the displays of these works were reminiscent of the rental boxes of Akihabara, a Tokyo neighborhood known as an otaku hangout, where stores commonly provide these booths for people to display pop culture paraphernalia that they wish to sell. Considering the gallery itself is a commercial space for the display of wares, this oblique reference to stacks of rental boxes served as a humorous link to otaku culture.

The exhibition showcased works that are emblematic of Mr.’s iconic style, while providing a comprehensive overview of his artistic development and experiments with different mediums. Besides illustrating the possibilities of art as therapy for tackling the fear and loneliness in an otaku’s soul, with works that combine cute subject matter with emotional nuance, Mr. is also pushing otaku culture towards greater mainstream understanding and acceptance; one could clearly see his determination throughout the show.

Dennis Mao is an editorial intern of ArtAsiaPacific.

Mr.’s “People misunderstand me and the contents of my paintings [ . . . ]” is on view at Perrotin, Hong Kong, until October 20, 2018.