Shows

“Mould the wing to match the photograph”: The Mrinalini Mukherjee Archive

“Mould the wing to match the photograph”: The Mrinalini Mukherjee Archive

Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong

Sep 20–Feb 29, 2024

The recently renovated library of the Hong Kong nonprofit Asia Art Archive (AAA) shone a light on prominent Indian sculptor, Mumbai-born Mrinalini Mukherjee (1949–2015) in the exhibition “mould the wing to match the photograph.” Although Mukherjee was long-renowned for her hemp fiber and bronze sculptures of abstract deities, her 40-year career has recently received renewed international acclaim—in 2019, the Metropolitan Museum of Art put together a posthumous retrospective in the United States—demonstrating her enduring universality. As curators Noopur Desai, Pallavi Arora, and Samira Bose expressed, Mukherjee’s practice remains as evocative as ever, refusing to be confined by labels such as “feminist” or “Indian.” Rather, her work confronts universal experiences, evoking the transcendent beauty found within both the natural and human world.

When Mukherjee began garnering attention in the 1980s, many assessed the religious undertones in her work and use of traditional materials as being intentionally “Indian” or “crafty,” on the one hand eliciting orientalist Western commentary, and on the other, provoking Indian critics to assume she was “catering” to the West. For instance, after her first solo exhibition at the Oxford Museum of Modern Art in 1994, then-director David Elliott wrote that “aesthetic animism . . . positions Mukherjee’s work within its Indian context,” an interpretation that ignored the artist’s modernist touches, such as her works’ scale, their many erotic allusions, or her use of synthetic dyes to create vivid, colorful sculptures.

Elliott’s comments could easily be associated with Pari (1986), a red-dyed hemp-fiber soft sculpture that stands over two-meters tall. The Hindi title translates to “nymph,” imbuing the piece with an ethereal, figurative quality. Indeed, suspended from the ceiling of AAA’s library, the symmetrical, wing-like overhangs draped dramatically, transforming the quasi-vaginal sculpture into a spiritual portal. As Pari was exhibited in the room’s center, viewers were encouraged to observe it from every angle, anthropomorphizing the sculpture as if in reference to circumambulation, a common practice in Dharmic religions. Yet, one could equally interpret the installation as inviting audiences to forge a physical, sensual relationship with the piece.

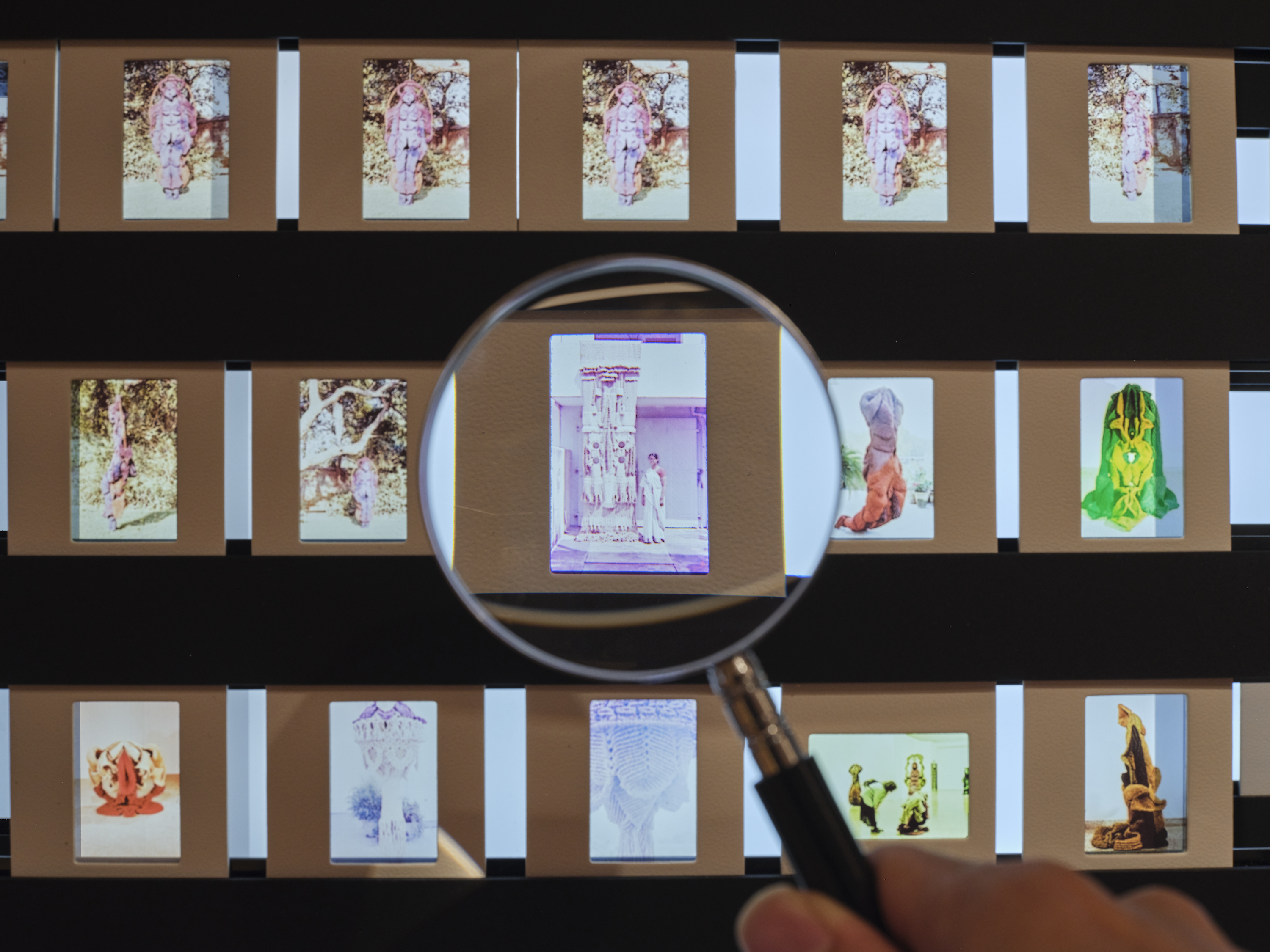

The display of Pari aligned with Mukherjee’s strict instructions on installing her work, which curators dramatically enlarged and cast them onto adjacent walls in the main reading room, still within eyesight of the sculpture. Reading “Distance from point x (point of suspension) to the floor should be EXACTLY 215cm,” viewers were thrust into a complex visual dialogue between the artist’s original vision and her final product. Contrasting with the oversized notes, a wall of lightbox vitrines contained 700 miniscule 35mm slides, perpetuating the exhibition’s experimentation with scale. Viewers were empowered to pick up and examine the photographs or move sliding shelves, personally experiencing Mukherjee’s sculptures in a more tactile way than museum settings usually permit. Despite her practice’s fluid, improvisational nature, she was apparently fastidious about documenting the final form, defying how art critic and curator Chrissie Iles once claimed her practice suggests a “pre-technological way of knowing the world.”

An interesting dichotomy persisted between the artist’s use of natural materials, methods, and subjects and the curatorial use of technology. Contact sheets, which included frames of her sculptures documented from multiple angles, were compiled in a stop-motion animation and displayed on two small tablet screens. A separate digital screen showcased more scans of the artist’s installation and packing instructions—one note proclaimed: “The sculpture should be moulded into shape with hands to maintain the critical dimensions and shape as in the photograph,” illuminating the exhibition title without forcibly explicating it. Between their knotted textures, bright colors, towering statures, and multiple visual, religious, and sociopolitical references, Mukherjee’s sculptures can sometimes be overwhelming. But, although condensed, her archival materials provided context and emphasized connections, rejecting oversimplified, orientalist analyses of the works’ “Indian-ness.”

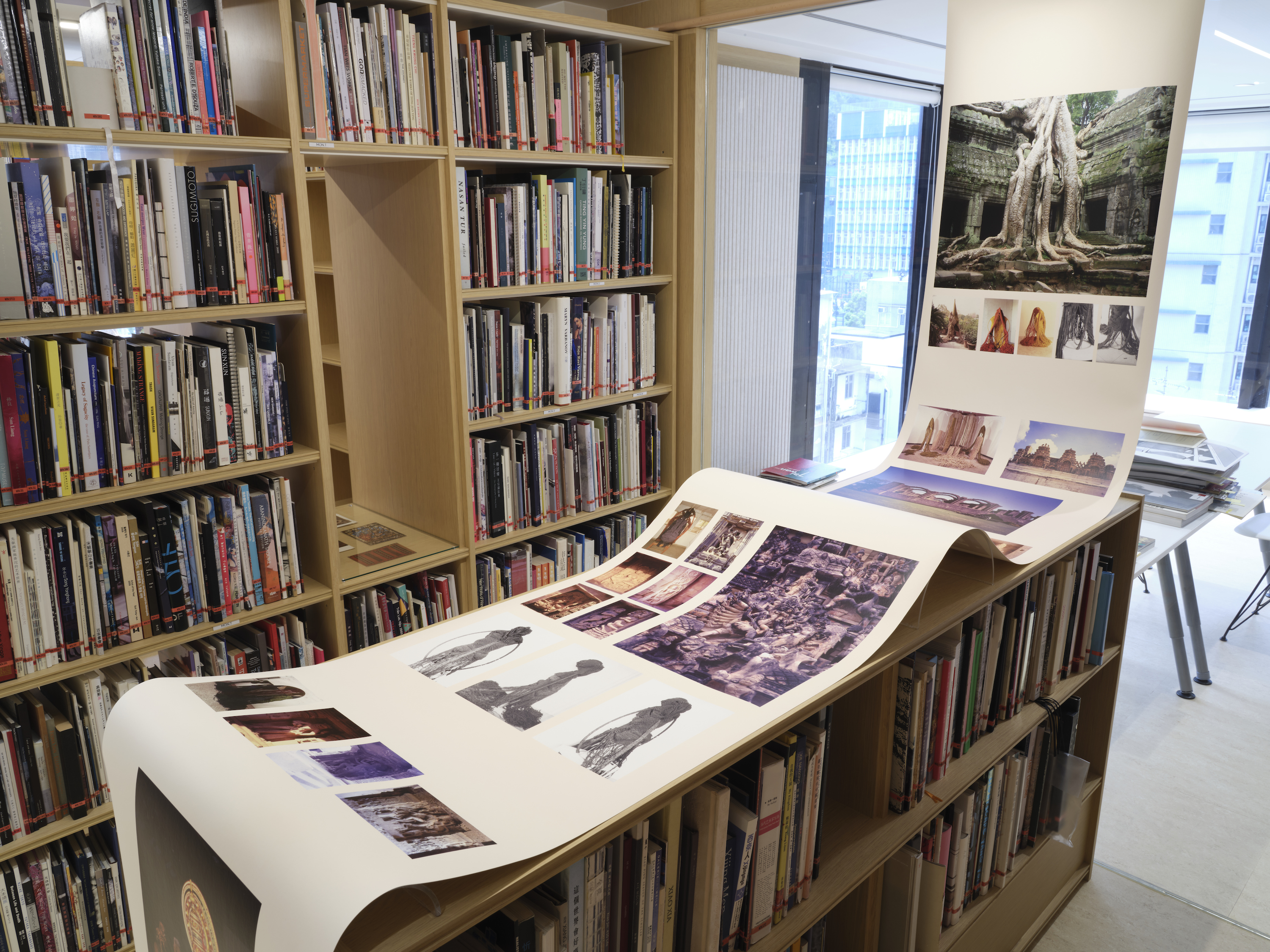

Mukherjee’s cultural allusions were further expounded in an adjoining room, as her personal postcard collection and the curators’ large, scroll-like display referenced images from her travels (the roots of a banyan tree cascading over a structure at Angkor Wat; stone depictions of Hindu deities in temples across India) next to pictures of her sculptures. In doing so, the AAA drew a clear parallel between Mukherjee’s visual inspiration and her work, at once demystifying and complicating its symbolism. While a photograph of a Javanese performance on the bottom of the scroll recalls the exhibition’s earlier animation—insinuating that staged movement was inspirational to the artist—it likewise undermined prior analyses that exclusively associated her work with Indian religiosity. Here, the AAA clarified that Mukherjee was influenced by a vast array of imagery, including architecture, nature, and cultural traditions across Asia. Returning to Pari after viewing the archives, one might observe newfound symbolism in the sculpture, which concurrently depicts mythology and sexuality; fluidity and structure; weight and flight.

Despite displaying only a single work, Pari, the curators created a vivid relationship between Mukherjee’s artwork and informative material throughout “mould the wing to match the photograph.” Relying almost entirely on archival documents, the exhibition countered any propensity to jargon-ify the artist’s visual language, instead using optical cues and tactile technology to guide the viewer experience. Staged in an intimate library setting, one can feel Mukherjee’s presence conducting the exhibition, reviving her work’s relevance while opening her practice to wider perceptions.

Anna Lentchner is assistant editor at ArtAsiaPacific.