Shows

Lydia Ourahmane’s “Survival in the Afterlife”

Upon entering Lydia Ourahmane’s solo exhibition in Amsterdam, one was instantly struck by a serenity that countered the dreary images evoked by the exhibition’s title, “Survival in the Afterlife.” Though the exhibition revolved around the House of Hope, a secret community of Christian converts founded by the artist’s parents amid the rise of Islamic fundamentalists during Algeria’s décennie noire—the dark decade of the 1990s—the artist handled the heavy past delicately, leaning into de Appel’s brutalist architecture and its acoustics to deploy her recurring tactic of mobilizing the visitor’s body, asking them to privilege experiencing over looking.

It is worth pointing out that in postcolonial Algeria, Islam was “defended as a metonymy of public order and as the symbol of national unity” by the government, as scholar Nadia Marzouki puts it in a book she co-authored, titled Religious Conversions in the Mediterranean World (2013). To convert to another religion often (wrongly) associated with foreign forces, then, was very controversial. Inversely, the discourse around Christian minorities is easily instrumentalized by Western institutions, notably in a context where Islamophobia is present—it allows such institutions to portray non-Muslim minorities as a peculiar version of “the other,” one that is different enough to remain exotic, yet similar enough to be acceptable. Ourahmane avoided overtly tackling the sociopolitical facets of the House of Hope. A form of refusal, this elusive approach allowed her to deftly circumvent tokenism and facilitate an understanding of the commune that is beyond identity-based debates.

Demanding that guests feel while eschewing the violence of a voyeuristic gaze, the exhibition was almost devoid of objects. On the ground floor, a composition of ambient music titled Notice the direction of fires (2021), realized in collaboration with Yawning Portal, bathed de Appel’s vast Aula in a meditative atmosphere. Only a set of 50 or so thin, multicolored mattresses occupied the center of the room. Placed orthogonally, they formed a grid that expanded discreetly in the space. To the side lay a pile of hand-sewn pillows for the audience’s use. Vibrant in colors, varied in patterns, and sometimes marked by evocative words like “skepticism,” these were made by the artist and her friends, and form the body of work Closures (2021)—a title that hints at the symbolic force of weaving together scraps from a bittersweet past.

This spatial configuration had a functional purpose—offering the visitor a place of respite to listen to the hour-long track—but it also had a conceptual and formal aim. While the curatorial inanity of transforming exhibition spaces into places of hospitality has become trendy (if not trite), Ourahmane’s domestic apparatus hints at the communal aspects of the House of Hope. In an exhibition dealing with a religious community from a deeply personal perspective, these scenographic gestures were rites of passage that primed the audience for accessing a sensitive, almost sacred, material.

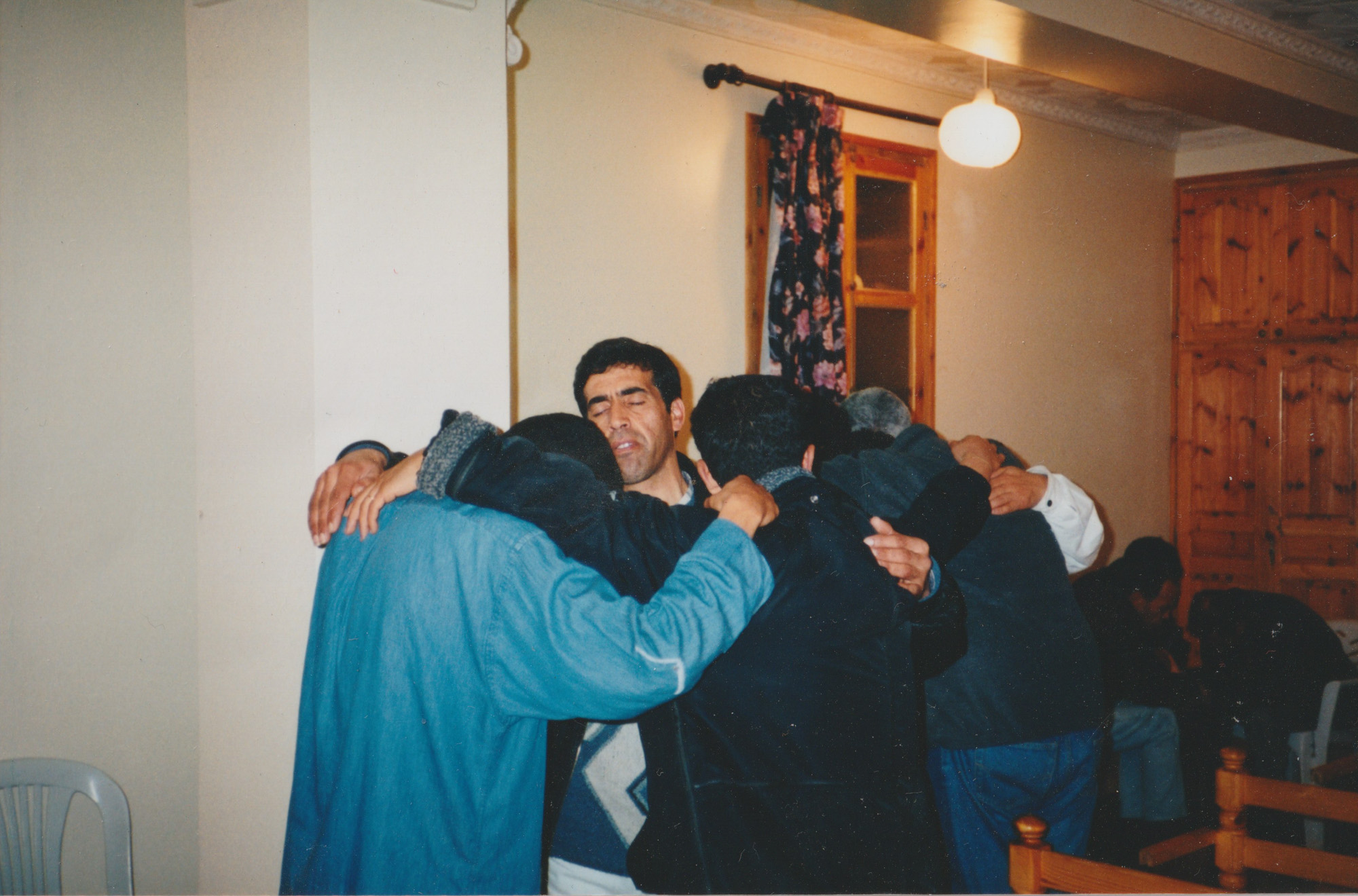

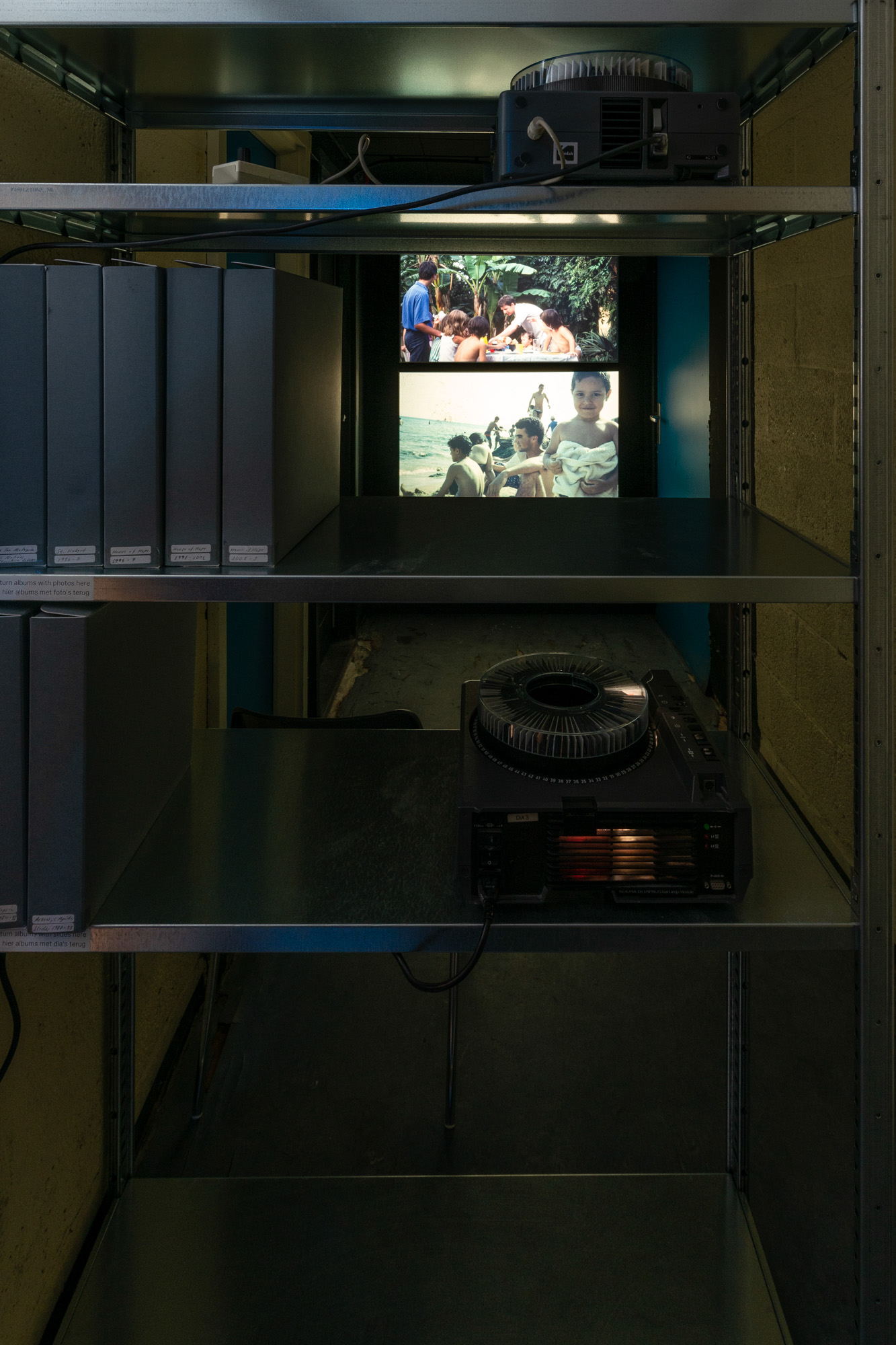

The lower floor held the show’s core—mostly photos belonging to Ourahmane’s family, the few remaining visible traces of the House of Hope’s history. Recalling institutional archives, the materials were accessible under a precise protocol: phones had to be left at a desk, and gloves had to be worn. The images were organized in files placed on a shelf, next to a thesis on the commune written by Ourahmane’s sister. To the right of this was the richest part of the show: a series of photo slides running through a projector. Much like home movies, these reactivate a nostalgic sense of domesticity. As the projector clicked, images of adults and children cooking, eating, and dancing, often smiling at the camera or laughing with each other, appeared. It is striking that in an exhibition centered on a religious commune, there were scant doctrinal specificities. Apart from a snapshot of what may be a bath or a baptism, and a small cross hung on a wall in another photo, religious symbols were absent. In this way, the artist conjured an idealized version of the commune: that is her prerogative. This subjective depiction of the House of Hope emphasized the possibility of forming informal networks of resistance in times of war. What transpired was a collective joy.

Lydia Ourahmane’s “Survival in the Afterlife” was on view at de Appel, Amsterdam, from September 22 to November 23, 2021.