Shows

Lee Bul’s “After Bruno Taut”

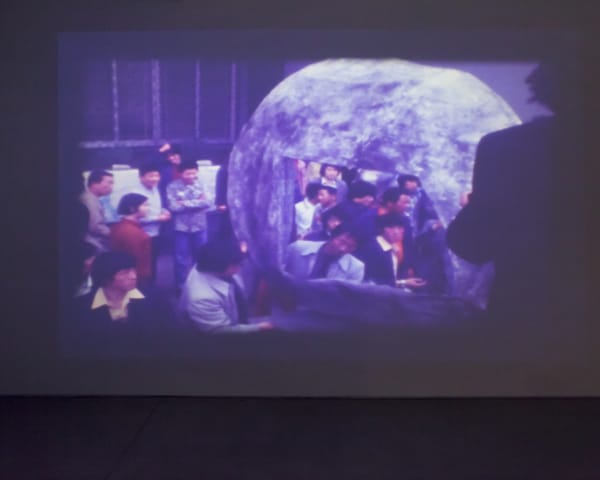

The title of Lee Bul’s exhibition “After Bruno Taut” at London’s Thaddeus Ropac refers to the development and publication of Alpine Architecture (1917), a collection of sketches and watercolors for a utopian urban architecture conceived by the German architect that would ideally grow from Western Europe’s Alpine mountains. Ideologically opposed to the utilitarianism and crude materialism that he believed had led to the First World War, Taut was especially interested in glass as a building material, inspired by the work of his friend Paul Scheerbart—an architectural theorist and author who celebrated its propensity to let light in and effect human experience in his most well-known book Glasarchitektur (1914).

The issue with looking retrospectively at an artist or architect whose work was consciously engaged not just with the aesthetic world, but also social and political conditions, is that contexts inevitably change. In the century since the publication of Alpine Architecture (1917), glass buildings have evolved far beyond the spiritual, functionless forms envisaged by Taut. Rather, in many cases, they are the sites of business transactions and international finance. Even as early as 1921, the urban-utopian potential of glass was in question when Yevgeny Zamyatin, in his novel We (1924), used glass buildings to create a uniquely panoptic dystopia, prefiguring the anxieties over surveillance that mark our times.

The centerpiece of Bul’s exhibition, After Bruno Taut (Beware the Sweetness of Things) (2007), is a formally stunning object, but beyond this suffers somewhat with regards to context. This remarkable, spiraling structure of crystal, glass and acrylic beads, mirrors, stainless steel, aluminum and black-nickel rods, bronze chains and aluminium armature is markedly more complex in form than most of Taut’s original sketches—which were largely geometric, crystalline and symmetrical—and with the prominent use of beads and mosaicked mirror seems too extravagant to truly be an answer to the German mystic’s ideas. The helix-like towers that rise from its hanging body are more redolent of Vladimir Tatlin’s unbuilt Monument to The Third International (1919–20) than anything Taut ever designed. And in the whitewashed but nonetheless conspicuously ornate rooms of the grand 18th-century Mayfair townhouse in which Thaddaeus Ropac was opened last year, the hanging work risks seeming less like a socially conscious maquette for an exciting utopian architecture in the style of, say, Constant Nieuwenhuys and his speculative architectural project New Babylon (1956–74), and more like a glitzy if well crafted chandelier.

As with so many contemporary exhibitions, the body of work here really comes into its own when attempts to situate it with ex post facto titles and texts are put aside. Considered on their own merits and within their own context, attention to form alone gives these works ample value. The thick, heavy, flowing boughs of the wall-mounted Untitled (Sculpture M3) (2013), for instance, have the resinous quality of something that has formed in accordance with natural forces, and yet gather at times into twisted mechanical joints. The sculpture’s surface, covered with mirrored tiles, is a shining mosaic up close, a curlicue of metallic alligator skin from a few steps away, and a twisting mass of once molten lead from a distance.

Mounted on an opposing wall, Untitled (Sculpture M1) (2013) is far more angular and less organic, and yet manages to combine sharp lines and asymmetric curves in such a way that its artifice, where visible, appears more crafted than industrial. Lacking any solid core, its metal rods and meshes are bound so as to resemble a mechanical analogue to the kinds of straw talismans traditionally made the world over, and the softness of the intricate shadows they create complements the severity, even violence, of the central object.

There were several works entitled Civitas Solis (2015)—referencing the Latin title of the early utopian text by the Italian Dominican philosopher Tommaso Campanella, The City of the Sun (1602)—which consisted of framed acrylic mirrors whose surfaces appear cracked and rearranged so that the reflections they create are distorted. Again, their context does these works no favors. As comments on selfhood they seem trite, and as possible critiques of utopianism they are underdeveloped. However, as forms in themselves they are compelling, and this was the problem with “After Bruno Taut”: Lee Bul’s works speak for themselves, often so powerfully that to take pieces from previous exhibitions and lump them together under a thematically suggestive and particular title is to cross conversations.

Lee Bul “After Bruno Taut” is on view at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, until February 10, 2018.