Shows

Highlights from documenta fifteen

For all its by now extensively analyzed, criticized, and theorized failings, this year’s Documenta is nevertheless a total treat for Europe-based audiences to get acquainted with collectives and scenes that might otherwise remain distant. Where else would I discover the likes of Wakaliga Uganda, for example, a film studio based out of an eponymous slum in Kampala that engages disadvantaged youth through moviemaking? Here with an exhibition of handmade posters and films, the studio is winning fans for its new feature, Football Kommando (2022), which premiered at Documenta’s opening.

Now in its 15th edition, the quinquennial currently occupying the German city of Kassel has been generating headlines for all the wrong reasons. First was fascist graffiti at key venue Werner-Hilpert-Strasse 22, also known as WH22, which hosts Palestinian collective The Question of Funding. Next was the discovery—and hasty removal—of antisemitic imagery in a 2002 mural by Indonesian group Taring Padi. The incident has led to intense criticism of curators ruangrupa and calls for everything from criminal prosecution to closer supervision of the festival’s EUR 42 million (USD 43 million) budget moving forward. In July, one of the festival’s bigger names, German artist Hito Steyerl, pulled two works from display in response to the curators’ handling of the controversy. Amid mounting pressure, Documenta’s director general, Sabine Schormann, resigned.

The fiasco is a disappointing distraction from what ruangrupa’s Documenta promised and, in parts, delivers. With some 1,500 artists, the edition is the biggest in the festival’s 67-year history, and remarkably, only the second to be led by non-European curators after Okwui Enwezor in 2002. A collective founded in Jakarta in 2000, ruangrupa invited 14 groups and 53 artists to participate as part of an underlying concept of lumbung, which means “community rice barn” in Indonesian. Here, lumbung is a metaphor for a collective approach to art-making and resource distribution. Those invited by ruangrupa subsequently invited a seemingly open-ended number of participants, sending the number of artists spiralling. After Covid forced us all apart, and pandemic travel bans highlighted the vulnerability of a highly centralized art world—as well as opportunities beyond—ruangrupa’s premise of a community-oriented, sustainable platform that challenges art’s murky approach to “value” and inclusivity felt just like what we all needed.

Case in point: its commitment to diversity, which includes people with disabilities courtesy of the festival-wide presence of British lumbung member Project Art Works that comprises neurodiverse artists and activists. Elsewhere, Copenhagen’s Trampoline House quite literally amplifies the unheard voices of Syrian asylum seekers in Sudanese artist Khalid Albaih’s sound installation, The Walls Have Ears (2022). Located in a pedestrian tunnel, the work comprises a series of listening posts playing the testimonies of asylum seekers in Denmark.

This striving for a more inclusive, equitable art world is visible elsewhere. Brazilian artist Graziela Kunsch’s Public Daycare (2022), for example, provides free daycare for babies up to the age of three inside principal Documenta venue, Museum Fridericianum. The fair division of economic resources is also a central thread of the show and explored through lumbung Kios. The kiosk network is a platform for participants and local businesses to sell products. Its most playful iteration is a series of vending machines by Rural School of Economics, an initiative by Dutch collective Myvillages. For a handful of euros, visitors can buy items crafted by local social enterprise organizations, including Violets Against Violence’s purple crochet flowers to support female victims of violence.

Works are located in four main city districts: Mitte, Bettenhausen, Nordstadt, and along the Fulda River. Sites span the conventional and the unexpected, from five Kassel museums to a compost heap, sixteenth-century defensive tower, and storefront. Highlights of the former include the labyrinthine basement of Museum Fridericianum, where Uzbek artist Saodat Ismailova brought along 18 members of DAVRA, a collective she founded in 2021. The group’s output includes films and a program of workshops and performances centered around the Central Asian mythology of chilltan: 40 shapeshifting spirits with a plethora of connected rituals. On my visit, artist Aïda Adilbek was sifting rice at the space’s central wooden table ahead of her colleague Diana Rakhmanova’s performative preparation of a traditional pilaf in tribute to the mythical entities. Next door, traditional Uzbek mattresses were strewn about, inviting visitors to watch Ismailova’s mesmerizing film, Bibi Seshanbe (2022), about a Central Asian Cinderella-like figure, female spirituality, and rites of passage.

Also occupying one of Kassel’s museums, the Hessisches Landesmuseum, is a new film by Berlin-based Pınar Öğrenci exploring issues of oppression in the artist’s native Turkey. Behind a curtain of hand-sewn paper tissues—a symbol of mourning—crafted by women impacted by the ongoing Kurdish-Turkish conflict, is a screening of Aşît (2022), which means “avalanche.” The work revisits Öğrenci’s father’s hometown, Müküs, close to Turkey’s border with Iran. All deep drifts and shoveling snow, the film recalls the 1915 Armenian genocide, and the families, language, and yarn tradition that were lost.

Striking a spiritual synergy is Haitian collective Atis Rezistans inside St. Kunigundis Roman Catholic Church. Showcasing the group’s Ghetto Biennale, which was established in 2009 and celebrates artists working in the Grand Rue neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, the exhibition drew connections between vodou practices and its church setting. For example, the wheel cap “halos” of André Eugène’s sculptures are made from scrap metal, tires, and automotive parts. Elsewhere, the Haitian and Belgian duo Michel Lafleur and Tom Bogaert’s sculptural columns Famasi Mobil Kongolè (2017), adorned with blister packs of medication, fairy lights, and tinsel, recall the country’s mobile pharmacies and appear as shrines.

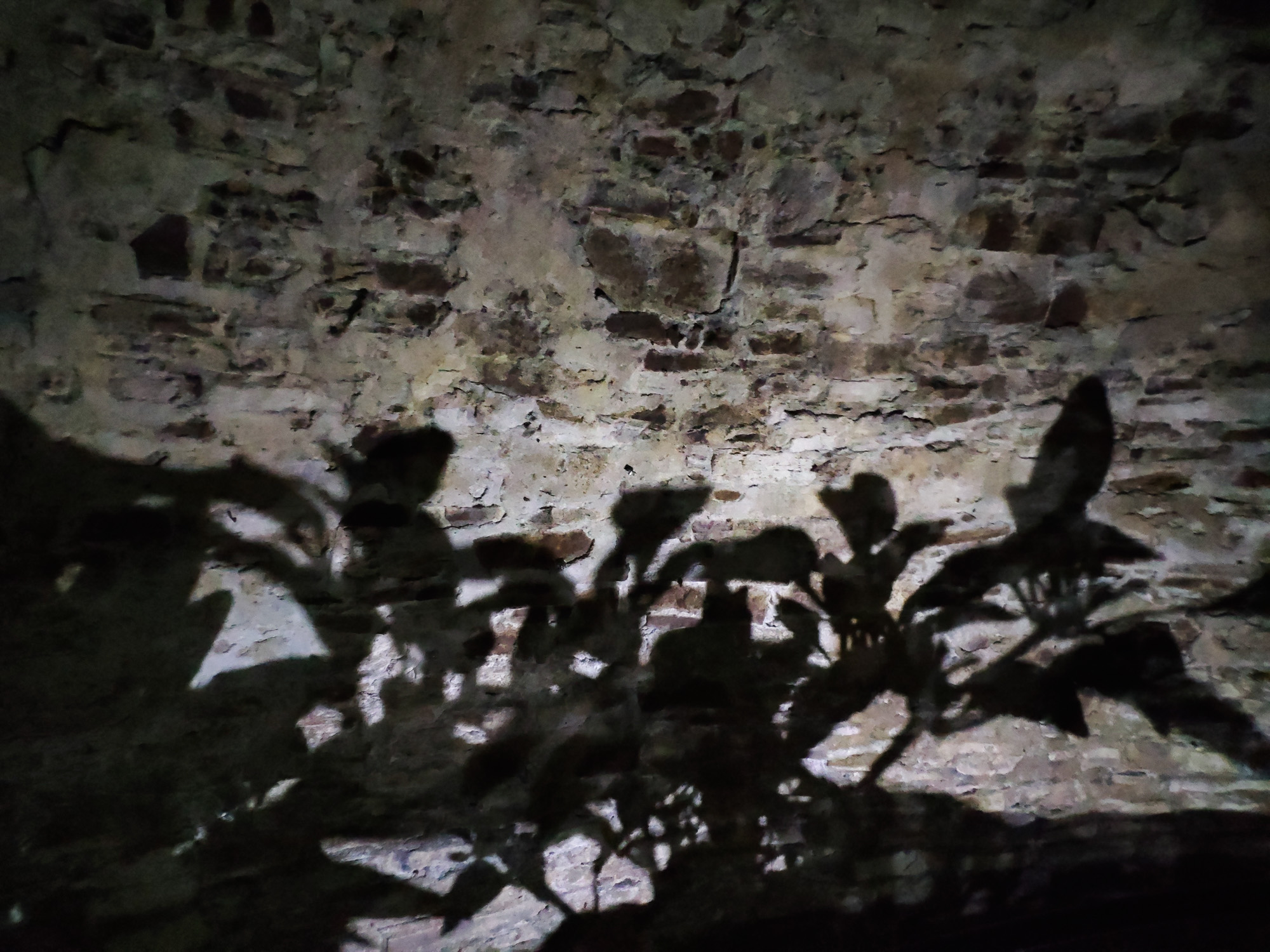

Also playing on its evocative Kassel setting was a new work by Vietnamese artist Nguyễn Trinh Thi, And They Die a Natural Death (2022). Comprising the shadows of birds-eye chilli plants and wind recordings from Vietnam’s Tam Đảo forest, the installation was inspired by a literary description of a 1960s prison camp. The light and sound projection takes place in the Rondell, a stone-built tower along the River Fulda, dating from the Middle Ages. The building’s impenetrable walls and tunnels with low ceilings recall the oppressive atmosphere of a wartime prison, while the tower’s crisp temperature evokes the forest’s cool shade.

Other presentations were more participatory in nature. At the more playful end of that spectrum was Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture, who drew connections between Kassel and the collective’s home village of Nongpho, Thailand, through their respective dairy farming traditions. Their large-scale installation depicts the Hindu myth of Churning the Ocean of Milk, while member artists invited visitors to try their hand at making shadow puppets from dried cow hides. To further cement the creative ties between Germany and Thailand, a local skate club has been invited to erect a skateboard ramp.

In the same venue, Bangladesh’s Britto Arts Trust looks to food in terms of identity, trauma, and community. Rasad (2022), a kiosk-like installation of ceramic and crocheted foods, is rendered sinister by visual signifiers of conflict such as torpedo-esque fish and pineapple hand grenades. The installation is positioned next to Chayachobi (2022), a large mural comprising scenes from Bengali movies depicting food crises. Outside, a pergola-covered garden guides visitors to an open-air kitchen where they can also volunteer to cook.

In parts, Documenta’s spirit of activism, care, and inclusion alluded to an intoxicating alternative to our current art world reality. For the most part, there is so much to discover in this educational trove of dispatches from the Global South. Yes, the lumbung concept is ambitious, idealistic, and in hindsight, fraught with risk. It also remains to be seen whether the German government will sign off on such an experimental Documenta ever again. That would be a pity, because as ruangrupa has—sometimes clumsily, sometimes deftly—shown, there are so many ideas, initiatives, and art that are worthy of our attention.