Shows

Heman Chong’s “This is a dynamic list and may never be able to satisfy particular standards for completeness”

Heman Chong

This is a dynamic list and may never be able to satisfy particular standards for completeness

Singapore Art Museum

Singapore

May 10–Aug 17, 2025

Heman Chong has a wry way with words—and knows how to put them to work. His 2016 text-based work appropriates the Wikipedia legal disclaimer, “This is a dynamic list and may never be able to satisfy particular standards for completeness,” using it as both title and content to critique the slippery, provisional nature of knowledge in the digital age. When the phrase resurfaced as the title of his most expansive survey to date at the Singapore Art Museum, it appeared subtly on a banner above the ticketing counter—an easy-to-miss gesture of conceptual détournement that neatly sets the exhibition’s tone, encapsulating Chong’s enduring preoccupation with how meaning is constructed and his signature knack for quietly subverting institutional authority through semantic mischief. A prominent conceptual artist, curator, and writer based in Singapore, Chong’s practice stands apart for its dry humor and grounded engagement with the everyday. He weaves together the most banal of daily acts—reading, walking, writing, photographing, scrolling—not as mere routines, but as tools of inquiry that sift through bureaucracy and digital excess to interrogate the systems that choreograph contemporary life.

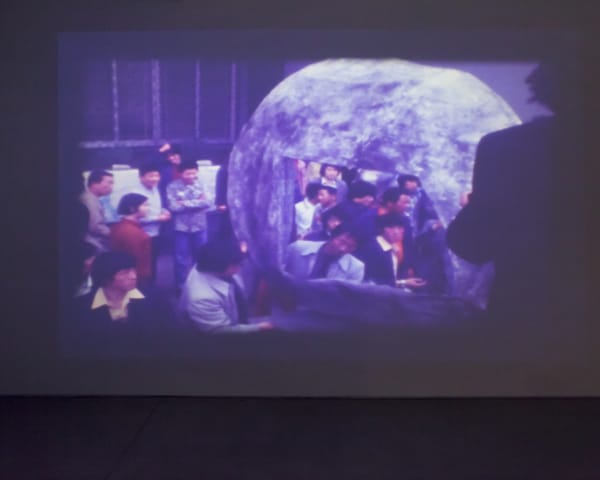

The exhibition opened with an assault of visual stimulation, most strikingly with Simple Sabotage (2016), a floor-to-ceiling installation of recurring reproductions of a declassified World War II manual issued by the US Office of Strategic Services detailing tactics to undermine the Axis powers from within. The dense grid of repeated text evoked the cognitive overload of digital life and the quiet oppressiveness of systems that govern how we see, read, and comprehend information, revealing how banal bureaucratic acts subtly impair or uphold structures of power.

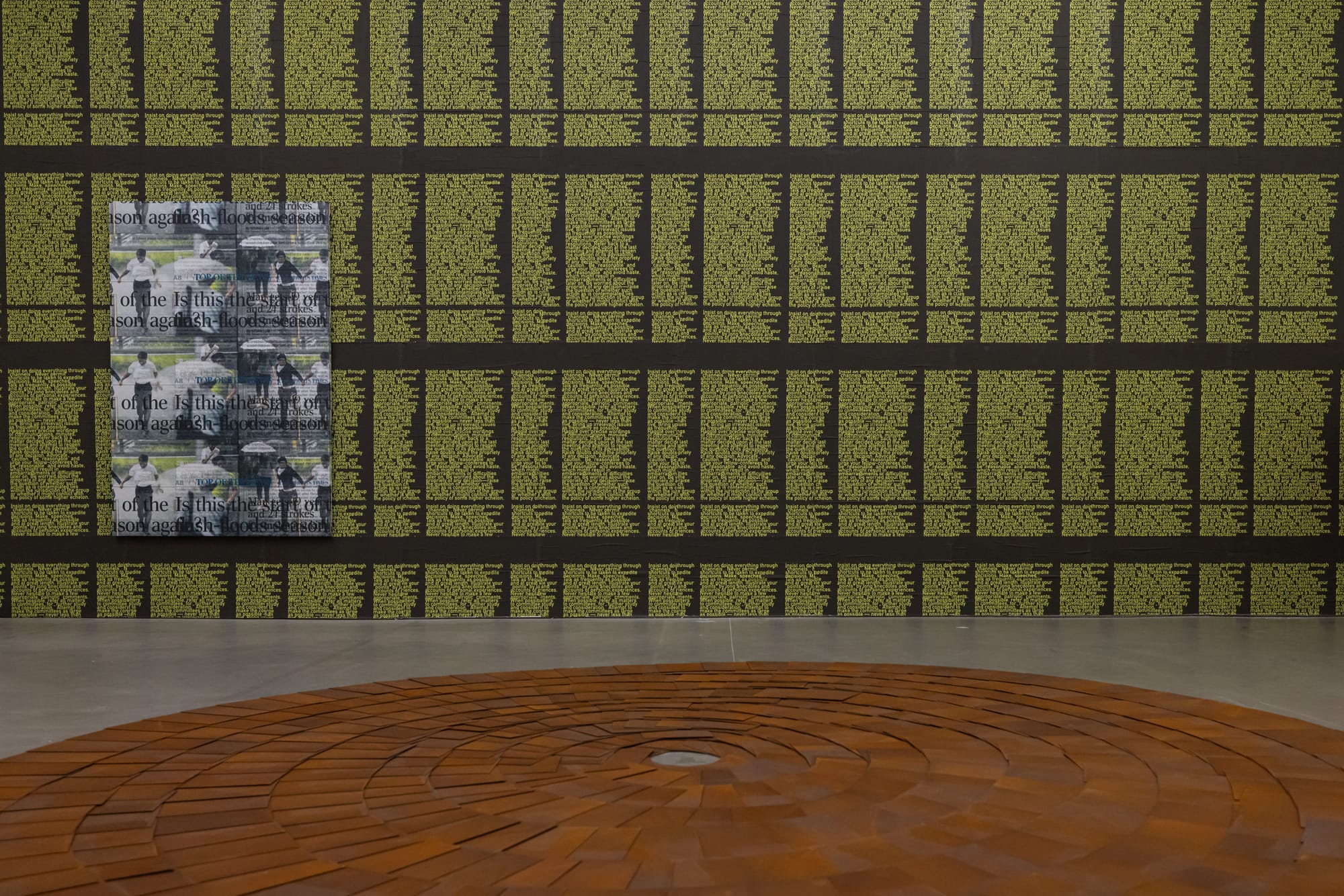

Printed media forms permeate Chong’s practice; deeply attuned to the interplay of text and image, he transforms existing materials with both the discernment of an avid reader and the precision of a graphic designer. In his Abstracts from The Straits Times series (2018– ), headlines and images from PDFs of the Singaporean daily newspaper are reproduced, layered, and blurred, creating visual palimpsests—glitch-like surfaces that expose how, in the digital age, truth falters and control unravels. This impulse to expose the absurdities of bureaucratic order was most sharply articulated in the text-based installation THIS PAVILION IS STRICTLY FOR COMMUNITY BONDING ACTIVITIES ONLY (2015), where Chong replicates a real state-issued sign with deadpan fidelity, turning it into a meme satirizing the government’s tendency to regulate even casual social interaction.

Strategies of repetition and variation recurred throughout the sprawling exhibition, which was organized into nine keyword-driven rooms mapping Chong’s core concerns. In Perimeter Walk (2013–24), 550 postcards featuring images Chong captured while walking Singapore’s peripheries form a taxonomy of everyday life. Neatly arranged in rows on stark white walls, they formed a clinical display evocative of an archive. Viewed head-on, the grid conveyed a sense of control; from a distance, it dissolved into a pixelated field of narrative fragments. Like several other works in the exhibition, the installation offered a quietly interactive experience—each postcard was available for purchase at a dollar, prompting visitors to reflect on questions of value, circulation, and authorship.

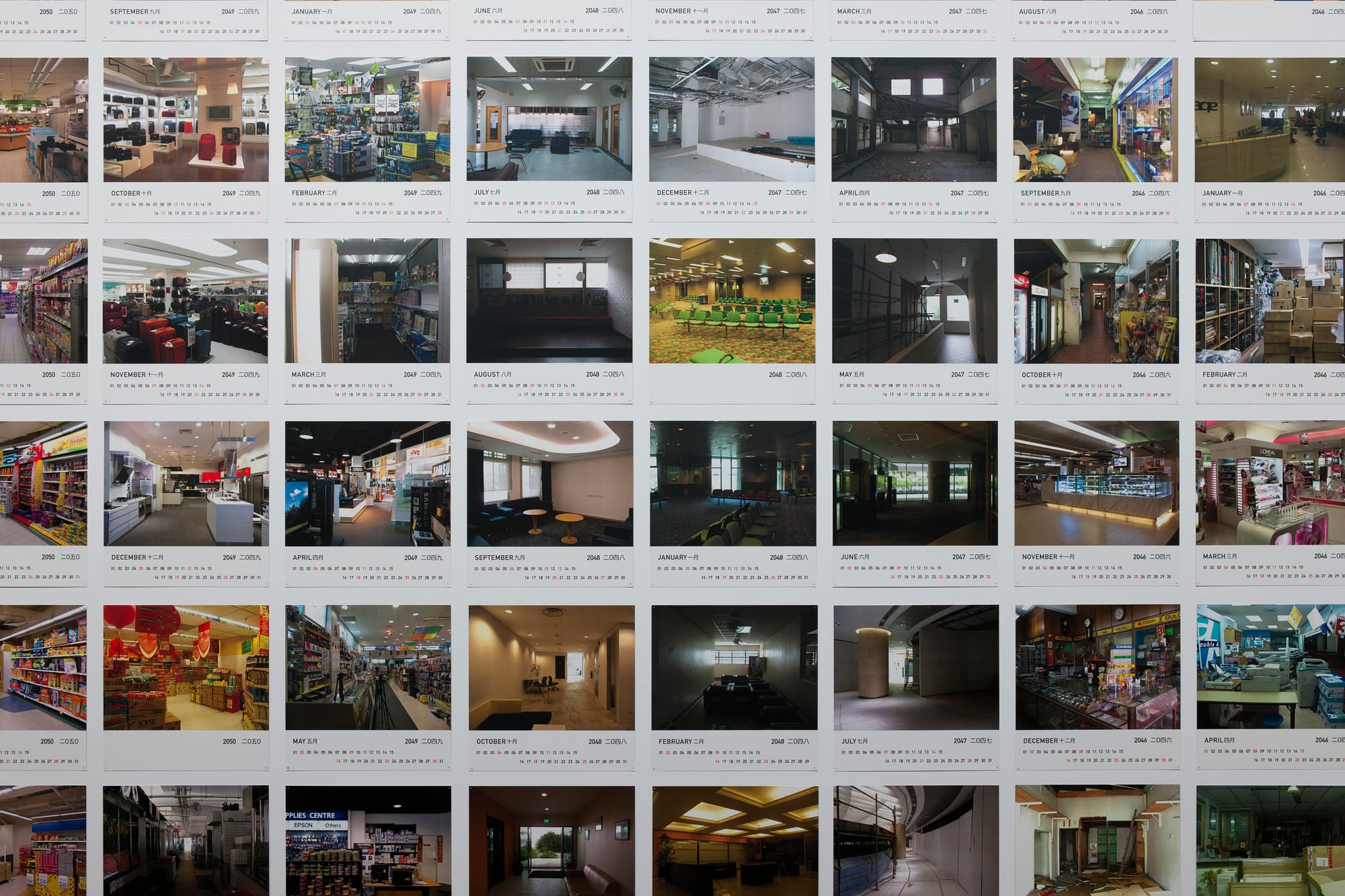

This rigor, echoing the restraint of Minimalism and the typological clarity of the Düsseldorf School, continued in Calendars (2020–2096) (2004–10), a wall installation comprising 1,001 images of empty public spaces—one for each month through 2096. The chronological sequencing suggested certainty or predictability, while the eerie stillness summoned a sense of suspended time, hauntingly reminiscent of pandemic lockdowns. Created in the past to chart a future, the work emanated a science-fiction quality, and reflected on how meaning is assigned to the unknown. The same aesthetic logic informed Foreign Affairs #225 (2018/2025), part of a series documenting unmarked back doors of embassies that Chong encountered during his travels. Here, the repeated image of a gold door appears on suspended fabric panels hung like curtains in the exhibition space. These textile partitions invited viewers to venture across thresholds typically sealed by pomp and protocol.

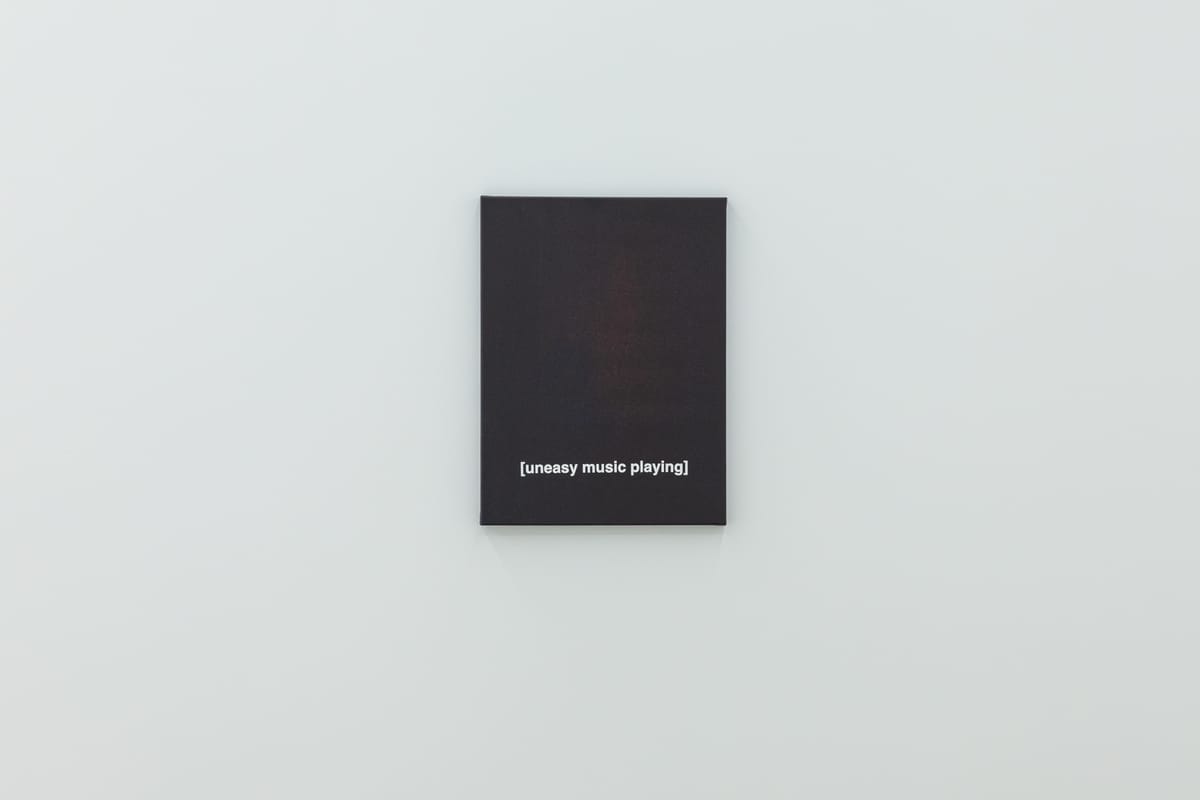

The exhibition also included works from several of Chong’s ongoing painting series, such as Cover (Versions) (2009– ) and The Hour of the Star (2013– ), which both highlighted his sustained engagement with literature and the dialogue between text and visual imagery. In the former, he imagines covers for books he intends to read; in the latter, he produces one painting a year, each inspired by a sentence from Clarice Lispector’s 1977 novel. This durational, accumulative approach recalls On Kawara’s Date Paintings (1966–2014) and recurs in Chong’s sculptural series Stacks (2003– ), where books and drinking glasses from the previous year are assembled together as quiet, totemic markers of time—ritualistic in rhythm, personal in trace.

The show culminated with Monument to the people we’ve conveniently forgotten (I hate you) (2008), a tidal mass of one million blacked-out business cards scattered in layered piles on the ground. Viewers were invited to tread over them carefully, their steps slow and deliberate to avoid slipping. Like the blank screens of mobile phones, the cards evoked a graveyard of devices—intended to connect yet deepening disconnection. As curator Kathleen Ditzig observed in her essay on Chong, the work’s scale and tactility re-discipline the body, making visible—and indeed palpable—the systems that shape and estrange our movements through the world.

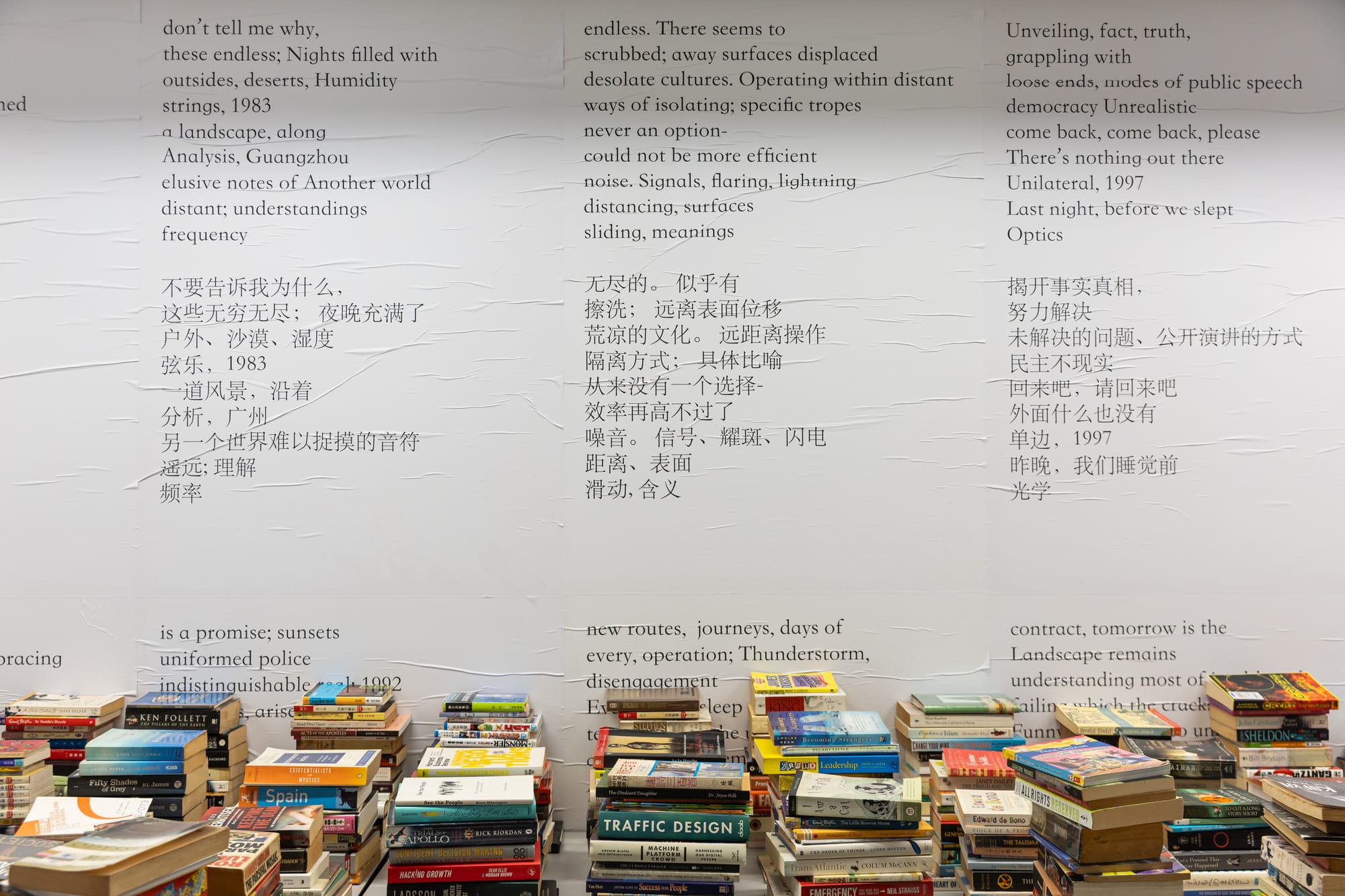

Yet this sense of alienation was not absolute. Upon exiting, visitors encountered The Library of Unread Books (2016– ), installed near the entrance. Developed with Renée Staal through a public call for donated unread volumes, the project was described by Chong as a “social sculpture”—a living commons that evolves with each iteration. As a space of shared knowledge where deferred intentions find unexpected solidarity, the work offered a quiet counterpoint to the exhibition’s critical stance. In Chong’s world, connection may falter, stall, or arrive dog-eared, but it endures.

Yvonne Wang is an art writer and ArtAsiaPacific’s Singapore desk editor.