Shows

Ghost 2568: Wish We Were Here

Ghost 2568: Wish We Were Here

Bangkok

Oct 15–Nov 16, 2025

As Amal Khalaf, current curator of Bangkok’s film and performance triennale, Ghost, introduced the work she had gathered, the city spoke over her. Sudden thunder erupted from behind high-rises, puddles choked the gutters, and livid sheets of rain hammered the tin roof of Dib26 project space, where friends of the multivenue festival had gathered. The sound was so aggressive, the group was left huddled together, voices drowned out, like a haunting of river ghosts. Yet perhaps it’s no wonder that the spirit of the city seemed determined to overwhelm her—Khalaf had assembled a collection of works that gave voice to the absences, the losses, and the forgotten histories that the city as we know it is built upon. The exhibition was a love letter to spaces and ways of life sacrificed to progress and profit, signed “Ghost 2568: Wish We Were Here.”

Outside the Bangkok Arts and Culture Centre (BACC), it was the growl of traffic and clamor of shoppers that saturated the air. In BACC’s outdoor plaza, Thai artist Tanat Teeradakorn rigged up a towering scaffold, crowned with a half-dozen, stark white loudspeakers. Throughout the day, CAPITAL COMPLEX (2025) trumpeted a megamix of audio recordings drawn from Bangkok’s frenetic history of push and pull between uprising and repression—protest songs, the barely audible frequencies of meaningful sites, and notes of state-sponsored propaganda. As the chatter of commuting and commerce merged with these historical sounds, Tanat set the tone for the triennale by insisting that the spectral echoes of past struggles remain forever part of the city’s sonic DNA. Yet as his recordings flowed out of the speakers and ricocheted around the concrete underbelly of nearby overpasses, the voice of the city’s past seemed to waft in from elsewhere; from everywhere. The equipment itself appeared eerily quiet.

Indeed, the search for traces of complex political legacies that lurk within the unexpected elsewheres of contemporary life animated many of the triennale’s most compelling offerings. At the Jim Thompson Art Center, Komtouch Napattaloong, Kaisa Saarinen, and Bart Seng Wen Long’s These Laticifers Keep Bleeding... (2025) humorously probed the ways that latex fetishism and the bloody histories of rubber extraction in southern Thailand are bound together. Their detailed three-channel video explored with cheeky curiosity a quirky cast of rubber enthusiasts and the kinkified mundane rituals of their everyday lives. Interspersed with stories of extraction, violence, and survival in the country’s rubber forests—such as the horrific Red Drum Massacre—the project examines the many lives of the material. At the film’s height, an awkward woodland encounter between a gimp-suited rubber man and Lady White Blood (a figure from southern Thai folklore, herself kitted out in a frilly white rubber bodysuit) wrily asserts how commodity fetish and cultures of labor stalk one another throughout our love affairs with such lucrative substances; contradictions encoded in their chemical makeup.

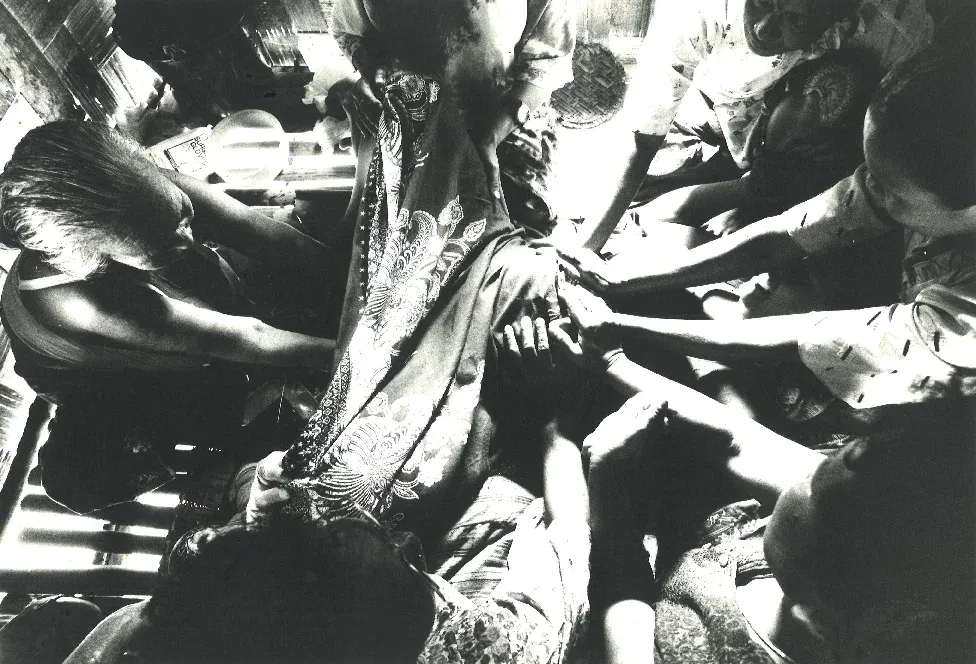

Across town at Baan Thewes, a reclaimed venue in a previously abandoned house, traditional Siamese midwife Tarini Graham attested to the potency of resistance at the cellular level. Alongside multidisciplinary collaborators Rosalia Namsai Engchuan, The Sound Nutritionist, Thairat Lim, Chao Mai Community Enterprise, and her children EMJA and Saeng-Fah, Graham offered holding the world between (2025), a recreation of a traditional birth hut and archive of Thai midwifery—bundles of fragrant herbs strung to the ceiling—to anchor performance and ritual that invited new audiences to channel centuries-old knowledge. Graham presided as the crowd sipped a botanical brew from warm clay mugs and released their spiritual burdens, whispering into handfuls of flowers, into the Chao Phraya River—their energies, perhaps, infusing the water and vice versa.

Hers is a banned practice that can be traced back to the court of Ayutthaya, one that she has carried forward despite contestation by Westernized medical practice, and even a kidnapping and attempt on her life. Guiding a captivated audience through her archive of photographs documenting the traditional practices that ushered her own child into the world, Graham spoke of her belief in the power held by ritual concoctions of inherited knowledge and intention. Just as Tanat’s sonic recollections of protest reverberate through the city, Graham’s practices spiritually nourish and resonate within a newborn, and thus the communities they grow into.

Her participation marked a welcome evolution. Here, Khalaf created space for those disenfranchised or rejected by the onward march of development. In past editions, such figures were alluded to but rarely present, as the programs were reliably stacked with a crop of artists that brought a vibe perhaps better suited for a Basel afters than a historic home on the water’s edge.

Khalaf was vocal about the role of the river as a starting point, central metaphor, and guiding spirit of this year’s triennale. Imagine it as the wet, still beating heart, wriggling at the center of a summoning circle. Before the concrete modernity of roads, such as Charoen Krung—a space well-trodden by curator Christina Li in the triennale’s previous edition—the Chao Phraya River once reached out into Bangkok, pumping life into the khlongs (canals) used to navigate the city, and sustaining the communities that lived along them. Khalaf’s rumination on a return to foreclosed spaces and abandoned ways of life is thus indebted to a river that she believes recalls its shape, breaks its banks, tries to “leak back” into places it once knew. In fact, multiple times throughout the duration of Ghost, the river leapt out of its bed and streamed back into the grounds of Baan Thewes, flooding the venue as if to be close to these works that speak to the power of past ways of being.

In Thai French artist Jeanne Penjan Lassus’s a jewel in the mud (2025), divers slip under the waters of the Chao Phraya in makeshift gear, their breath sent down beneath the waves through long coils of industrial plastic tubing. They trawl the bottom for treasures—twisted nails, pottery fragments, sometimes even jewelry—that have gotten loose from life, claimed by waters that suspend them in time, away from the rhythms of the everyday. Throughout her extensive research, these divers explained to Lassus the mirror-Bangkok of sunken buildings, dammed canals, and alternative geographies that are submerged within the river. Alongside her film, Lassus has laid out some of these objects in a winding formation at 469 Phra Sumen Road, a khlong-side art space. Her retrieval of these relics is a fitting thesis for Khalaf’s Ghost—exhuming both fragments of the past and clues to possible futures from the body of the river.

Having previously worked on projects that follow the Mekong and Indus rivers, Lassus implicates the waterways of Bangkok and the people who live along them in a global system of parallel concerns. At its most powerful, Ghost evoked the desire for return and reclamation as an impulse that overflows borders and defies colonial sovereignty. Weaving together textiles and film in Chotlung: traversing spirits, redemptive songs (2025), Kathmandu-based artist Mekh Limbu expresses solidarity with the Yakthung people and their resistance against an infrastructure project that would devastate their sacred mountain. We watched as they burned effigies of the proposed cable car—a prelude to the complex revolutionary violence that would sweep Nepal just weeks after filming.

Meanwhile, in the Sulu archipelago and in the Sabah of the Philippines, Australian Filipina artist Bhenji Raturns to ancestral knowledge through the pangalay dance. In Biraddali Dancing on the Horizon (2024), she perfects her craft under her mentor’s tender influence while drawing on legacies of trans sisterhood and expression from the community that gathers around her, ascending into the role of the mythical horizon-dancer Biraddali by the end of her sensuously hazy film. At Min Sen Machinery—another of Ghost’s reclaimed venues—she too weaves a thread of solidarity from the Philippines, through Bangkok, into the crises of the world at large, inviting us to witness her transformation seated on a woven mat that simply reads “FROM SULU TO GAZA.”

Initiated in 2018 by Korakrit Arunanondchai and Akapol Sudasna, the triennale has reached its third and final iteration. Its near-decade-long run has witnessed significant shifts within the Thai art world, with major biennales popping up faster than most can keep pace with and new, innovative projects taking root in various cities across the country. For Ghost, the measure of life well-lived seems not to be longevity, but legacy; the echoes that persist. This edition has seen several “returning ghosts”—artists such as Koki Tanaka and Orawan Arunrak—invited by the previous edition’s curator, Christina Li, to present newly evolved meditations on prior projects. For this iteration, Li organized “Ghost: Bodies Dispossessed,” a section within the triennale that connects the past lives of these projects to their revivifications, which will later be staged in Amsterdam.

Also returning are the triennale’s “Hosts,” a collective of docents trained to introduce the work; to let it speak through them. This year, the Hosts curated a version of Raqs Media Collective’s 18 Personae (2025) project, which offered chances to gather and revel in the idiosyncrasies that endure in the margins of life in Bangkok. While Host Jittarin Wuthiphan serenaded the graves at Teochew Cemetery with karaoke as his “Personae,” it became clear how a Ghost-ly gaze has informed a decade’s worth of participants, and the way they look at and commune with their city. Indeed, many of these young practitioners have gone on to form collectives of their own that now animate the scene—the spirit of Ghost not leaving us, just jumping hosts, set to haunt us for years to come.

Christopher Whitfield is a writer and educator based in Taipei.