People

As Told By: Asif Khan on the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture

It’s midday in September in Almaty. It’s hot, and the freshly planted long grasses in the landscape move in the breeze as passersby try to catch a glimpse inside Kazakhstan’s first center for contemporary culture.

Asif Khan (AK): Tselinny was once the biggest cinema in the Soviet Union. The main auditorium could seat over 1,500 people, and at its peak about two million visited each year. It was the IMAX of its time. It stayed full through the 1960s and ’70s, but by the late ’80s and ’90s television and satellite began to change everything, and the cinema went into decline. It was repeatedly renovated, divided, and rebranded. At one point it hosted nightclubs, a pizza restaurant, kiosks, even a furniture showroom in the foyer. By the time I first saw it in December 2017, its purpose had almost disappeared. It was clear to me then that it was not possible or right for this building to go back in time—it needed to move forward.

We pause near the street edge, facing the building and looking into the distance at the golden-domed church beyond it.

AK: Two things matter when we talk about its history. First, the Russian Empire; second, the Soviet Union. Behind the cinema you can see St. Nicholas Cathedral, built around 1900 as a symbol of the empire. That’s the first layer. Then, in 1964, the Soviets built this cinema directly in front of it, deliberately blocking the cathedral from view. I’ve been here at five in the morning many times these past weeks, and I noticed that the sun rises exactly along this axis. The first light hits the church, but the cinema stops it. That was intentional. You could say the cinema became the new congregation, the new place of belief.

We walk towards the entrance.

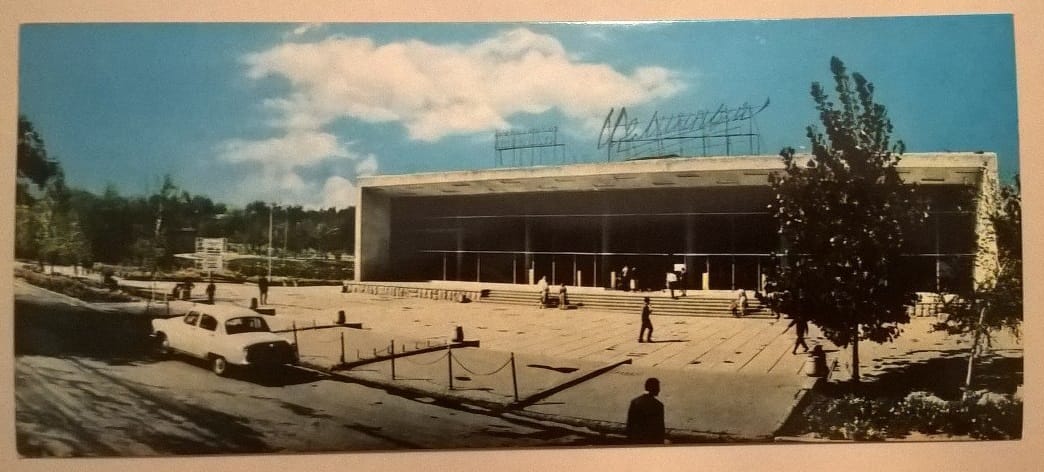

AK: A huge neon sign on the roof of its foyer once read Tselinny Cinema—in Cyrillic script. The word comes from tselina, meaning “virgin land.” It referred to Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands campaign of 1954, which brought half a million settlers here to plough the sacred Kazakh steppe and end nomadic life. Grazing land became wheat fields, and a way of life disappeared. So the name of this building, celebrating that campaign, carries its own wound.

Built for the tenth anniversary of the campaign, it was both a cinema and a monument to that rupture. Today there’s a growing effort to understand what was lost and reconnect with older cultural histories.

Historic photograph of Tselinny from the 1960s (left) and postcard of Tselinny (right), 1967. Copyright and courtesy Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

We stop by the main approach.

AK: The team existed before there was a permanent space. My future wife and collaborator on Tselinny, Zaure Aitayeva, was chief architect of the Astana Expo 2017, where I had designed the UK Pavilion. Through her I met Jamilya Nurkalieva, who would later become Tselinny’s institutional director, and Kairat Boranbayev, its founder. When they first invited me to see the site it was completely broken.

For us the answer began with the ground—both pre-Soviet and prehistoric. Almaty sits on an ancient delta where rivers from the mountains have been depositing stones for millions of years. Just below the surface are smooth, rounded rocks shaped by glacial water. We brought that hidden layer to the surface—my philosophy is that if buildings like this can regrow roots, perhaps people can find something that was missing too.

He crouches slightly, touching the paving.

AK: You used to climb six steps to get inside. We lowered it so that the floor meets the street, creating a continuous surface—a kind of common ground, like the steppe, where movement is free in all directions. The old cinema was a sealed box; now it’s open.

At the entrance.

AK: Instead of a doorway, I wanted a cloud-like threshold as the entrance. It softens the concrete frame of the Soviet building. It comes from my first visit to Almaty, when I saw a vast and beautiful cloud hovering over the steppe. I was sure it was Tengri, the sky god, waiting to return to Umai, goddess of the earth. The cloud is a symbol of that reunion: sky meeting ground.

Views of the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, Almaty, 2025. Copyright and courtesy Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

We move into the foyer.

AK: This whole front section had to be rebuilt because of seismic instability. We worked with the Kazniisa Institute to strengthen the old auditorium walls and roof so they could stay. The wings now hold a learning atelier, a café that opens to the landscape, workshops, offices, and below us a basement with kitchens, a cloakroom, and a quiet room for prayer and neurodiverse visitors.

During the works we rediscovered the 1964 sgrafitto by Evgeny Sidorkin. It had been dry-walled over and partially destroyed. Together with local experts like Almaz Ordabayev, a historian and architect who had known Sidorkin, we took the approach to repair and conserve it. The sgrafitto can now be seen again in full, but we have repaired areas of damage in ghosted white and overall used a muted palette so that the 42-meter-wide work is able to cohabit the space with the work of new artists and art forms—for example, the work of Dariya Temirkhan, which appears projected on the sgrafitto in the evenings as part of the opening show.

Outside, a new “cloudscape” of forms is embossed into the concrete wrapping the north and south façades. It’s a non-figurative language based on shapes from Sidorkin’s work—an abstract script, like memory half remembered. You’ll see its motifs repeated in windows, lighting, and in the staircases. Even the numbers and icons in the wayfinding system we designed echo the ancient petroglyphs at nearby Tanbaly, rooted in local memory.

He gestures to the windows running along the base of the auditorium.

A stainless-steel and glass ribbon wraps the ground floor, bringing daylight into the auditorium for the first time. The ribbon symbolizes the rivers I mentioned earlier, and these new doorways allow people to move completely in, out, and around the building.

We walk across the foyer.

The ground plane is continuous now; the old steps are gone. The landscape outside follows the same language—an ancient riverbed made from Almaty’s rounded stones, some tiny, some enormous, collected from across the region. They run through the site like traces of glacial water, grounding the building in its place. Fossil limestone from Mangystau forms the reception desk, and earth-pigmented concrete runs throughout the foyer.

Through here is Orta 1, the foyer space, leading to the café called Jer (Earth), designed by the local studio NAAW, the Capsule gallery, the flexible Orta 2 gallery, and the main Orta 3 auditorium.

He points upward.

The top floor is named Gülfairus, after the artist and actress Gülfairus Ismailova. She was probably the most important 20th-century Kazakh artist and wife of Evgeny Sidorkin. Her name appears throughout the wayfinding system. Her presence is a reminder of her creativity and the partnership that helped shape Kazakh modern art. From the roof terrace above you can see the Ile-Alatau mountains. For me she resides in that space above us, the intellect, the soul.

We enter the auditorium.

This is the original 18-meter-high hall. It once had tiered seating for 1,500; later it was divided into two smaller screens. We opened it again, strengthened it for seismic regulations, and brought light in. Now it can host performances in the round, films, art exhibitions—anything that can be imagined. At its center, a new work by Gulnur Mukazhanova has been installed—a large-scale textile piece that forms the heart of the opening performance, Barsakelmes. Last night’s show brought together 500 people—dancers, musicians, artists, sound, poetry, song, costume, movement—voices from the ancient past meeting this new space. People were in tears. It felt like a kind of healing for this building.

He points to a display in the adjacent Orta 2.

As part of the exhibition “From Sky to Earth,” curated by the Finnish architectural historian Markus Lähteenmäki, this is a series of dioramas made by a local craftsman, which we’ve named “Lesser Known Scenes from the Recent Life of Tselinny.” They show how extensive the reconstruction has been. Nearby, a larger model describes the completed building, and a study corner gathers drawings, photographs, and working materials from the studio. The five-meter-diameter circular table at the center is filled with models and photographs I’ve taken over the past eight years—through this journey with Zaure and with Tselinny—tracing significant moments of research, imagination, and experimentation. It’s a glimpse into how the project has evolved over the years, and what has influenced it. It’s like a mind map.

He gestures to another diorama.

This one depicts the time capsule by the artist Alexander Ugai, filled with 50 disposable cameras containing photographs taken by people close to the Tselinny family. It will not be opened until 2051. I guess it’s a reminder that this place already contains its own future.

Installation view of “From Sky to Earth” at the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, Almaty, 2025. Copyright and courtesy Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio.

He pauses, looking around the room.

It’s been a long journey to reach this point—years of work, discovery, and collaboration that have become part of the building’s story too.

Tselinny keeps its original name deliberately. Once it meant “Virgin Land,” a word of conquest. Now it stands for renewal, for fertile ground. The auditorium is designed without a fixed orientation so artists can use it freely, without hierarchy.

He pauses near the exit, looking out toward the street.

It took nearly eight years to bring the building to this point—6,000 square meters of architecture and the same again in landscape, in Almaty’s golden square. And there are more things to come: a rooftop restaurant, a learning space, a hidden tearoom, and a collaboration project with the neighboring Baitursynov Park, which will help to revive the cultural district we’ve inherited.

What was once a cinema has become a new kind of civic ground—a place where sky and earth, past and future, meet in the present. To arrive at Tselinny today and pass through that cloud is to receive ancient energies for life and for art.

Outside again, light shifts across the curving river form that undulates across the granite surface in front of Tselinny, which so effortlessly absorbs the street, bringing busy people on their lunch breaks within the building’s aura as they pass. There is a sense of anticipation in the air for tonight’s performance of Barsakelmes. Will it be even better than last night? We’ll have to wait and see. This is just the beginning.