Shows

Akram Zaatari’s “Tomorrow Everything Will Be Alright”

A small, two-room exhibition at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's (MIT) List Visual Arts Center features three short films by Lebanese filmmaker Akram Zaatari. The exhibition, entitled “Tomorrow Everything Will Be Alright,” scrutinizes the heteronormative expectations of Lebanese society, offering an exploration of male sexuality and the taboo of homosexual relationships. Zaatari interweaves documentary with storytelling: longing, distance and unrequited love are the major themes of these works, wrapped in the subtext of the territorial disputes in West Asia.

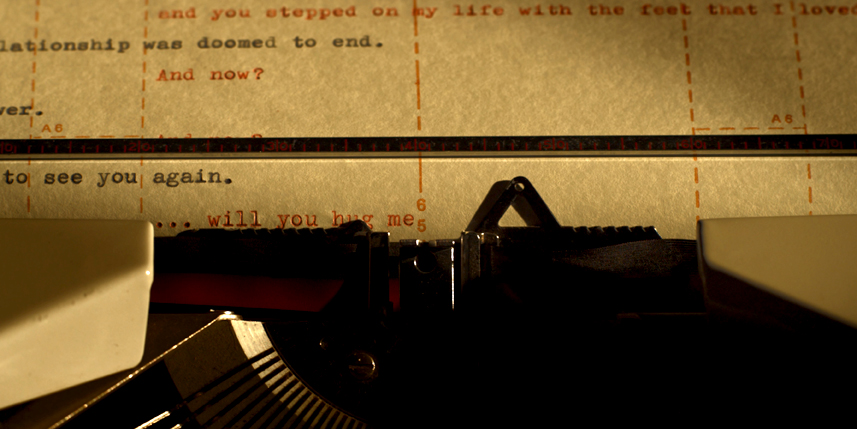

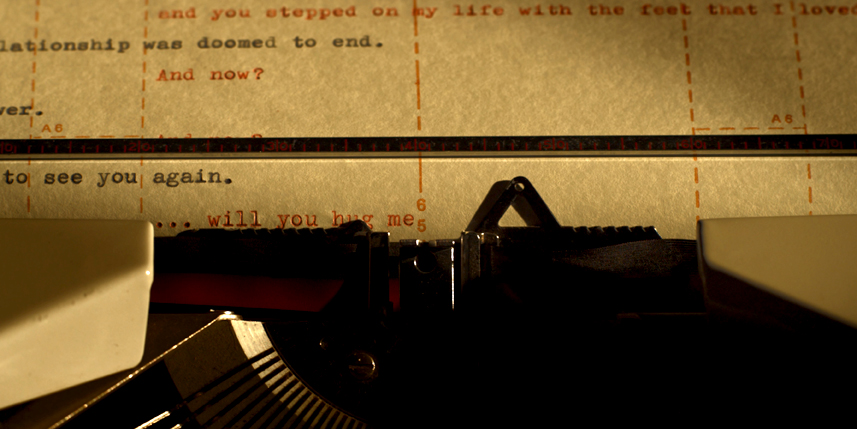

The exhibition’s eponymous film, Tomorrow Everything Will Be Alright (2010), is an epistolary conversation between two former lovers. Taking an unconventional approach to address the decade-long time lapse since the two men last communicated, the unidentified individual types on an outmoded typewriter, while the other man responds through the immediacy of today’s online chatting. The estranged lovers’ conversation is tempered by time. However, peculiarly, the film seems to lack a human touch. There are no actors; the narrative is transmitted through text. Tomorrow Everything Will Be Alright is one of the more moving works in the exhibition. The film gets to the core of a broken relationship, impressively conveyed without sound (aside from the score) or setting; instead, emotions are depicted with the use of an archaic medium—the typewriter. The audience is thrust into the relationship of two men without any knowledge of their past. Not given a context, the viewer experiences uncertainty, distance and the tension of an unknown outcome. The work is an homage to the filming process, recalling the initial stages of a film, i.e. the script. Shot with a Red One camera—a brand of digital movie camera known for its ability to achieve images akin to 35 mm film—the image looks grainy and raw, which once more provides a nod to an earlier era of cinema.

In the adjacent Bakalar Gallery, the films Red Chewing Gum (2000) and Nature Morte (2008) are featured on a back-to-back loop. Like Tomorrow Everything Will Be Alright, the ten-minute-long Red Chewing Gum similarly addresses the notion of love lost, but with a far more impassioned and erotic approach. The film’s narrator, speaking in Arabic with English subtitles, recalls a chance encounter between he and his male lover while observing a boy chewing gum in an alleyway. His flashbacks to Haram Street—the location where their love blossomed 15 years prior—are layered with the narrator’s storytelling. The play on power and desire in the men’s relationship is symbolized by a piece of chewed red gum exchanged between the two lovers while kissing, which seems to reflect on sensuous consumption and indulgence—they share the used Chiclets gum (an old, popular brand in Lebanon) and rejoice in the pleasure of each other’s company.

Though sexuality is a central theme in Zaatari’s work, he does not ignore the political arena. Nature Morte is a portrait of two bomb makers in the process of assembling an explosive device. In a dimly lit room prone to electricity shortages, two figures are shrouded in shadows, resolutely wrapping duct tape and cutting wires while the azan, the call to prayer, sounds in the backdrop. Filmed in the mountains and valley of the Shebaa farms, the contested area on the border of Lebanon, Syria and Israel. The location would be largely insignificant if not for the multiple, conflicting claims on the land. Here Zaatari portrays the scenario of a quiet town harboring a grandiose, malignant secret. In the final scenes of the film, the men who had earlier been casually constructing a bomb reappear at the border of Lebanon, beside a small, crude stone wall, overlooking the valley below and Israel in the distance. The men then part ways, one carrying a backpack—presumably filled with explosives—and the other, empty-handed. Stripped of cause and effect, Zaatari shapes an oddly serene portrait of bombers without overtly referring to their historical context, depicting the strange stillness at the heart of a hotly disputed yet desolate area.

The strength of Zaatari's work lies in its ability to capture fractured moments in time, even if these sometimes confuse because of their disconnect from the audience and lack of context. Regardless, the stories hold their own as fascinating narratives, managing to reflect on such universal themes as love and lust, and sweet reminiscence, even amidst turbulent political realities.