Shows

Aichi Triennale 2025: A Time Between Ashes and Roses

The Aichi Triennale 2025, led by its first non-Japanese artistic director, Hoor Al Qasimi, takes its title from Syrian poet Adonis’s 1970 collection of poems, “A Time Between Ashes and Roses,” which meditates on how destruction and renewal coexist within a single breath. This tension reverberates through the exhibition, echoing a world where the ashes have yet to settle and violence persists as a condition of life. Spanning regions, generations, and more-than-human lives, the triennale asks how we might resist exhaustion without succumbing to despair, and what art can offer beyond fragile hope amid unrelenting crisis. Spread across the Aichi Arts Center, the Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum, and Seto City, the exhibition addresses this question through curatorial gestures that root global dialogue in local ceramic traditions, foster intergenerational and cross-disciplinary exchange, and—perhaps most poignantly—allow each artist’s world to speak in its own time and register.

Lebanese artist Dala Nasser’s Noah’s Tombs (2025), an installation of clay, fabric, earth, and ash that forms an enveloping circular structure, evokes a site that has been resurrected after submersion. Retelling the biblical story of the flood that destroyed the world only to birth it anew, the work references locations in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon, believed to be Noah’s burial sites. Textures incorporating Japanese indigo dye and Ainu-inspired architectural motifs transform this transregional narrative into a space where apocalypse becomes not an end, but a horizon of renewal.

This insistence on regeneration amid devastation is echoed in Bassim Al Shaker’s vibrant painting series Four Minutes, one of which—Sky Revolution (2023)—is suspended from the ceiling. The Baghdad-born, New York-based artist reimagines the bombings he witnessed during the Iraq War as vibrant explosions of color against darkness, embracing life’s precarious, solemn beauty. Similarly rooted in histories of destruction and reclamation, Hrair Sarkissian’s Stolen Past (2025) bears witness to the damage wrought during the Islamic State’s occupation while actively seeking to recover what was lost. A series of 3D-printed lithophane panels mounted on illuminated plinths reconstructs stolen and destroyed artifacts from Syria’s Raqqa Museum, which once housed cultural artifacts spanning from the Paleolithic era to medieval Raqqa ware. Seeming to float out from their flat surfaces, the hauntingly tactile images embody an act of remembrance as protest, asserting the right to existence itself.

A strong undercurrent of continuity within destruction resonates in works that explore humanity’s entanglement with the natural world. Pioneering Sudanese artist Kamala Ibrahim Ishag’s intuitive painting Bait Al-Mal (2019) maps her childhood neighborhood through a vegetal cosmology, where human cocoons intertwine with tree roots, sharing nourishment and vitality, and grounding human life within the soil that sustains all beings. This sense of interconnected survival extends into Honolulu-based artist Solomon Enos’s painting series Pala (Ripe) (2025), which reimagines human-made waste as it re-enters nature’s cycles. In his canvases, discarded machine parts morph into hybrid organisms that merge with the natural environment, envisioning future ecologies where material excess becomes the seed of regeneration. Rather than romanticizing decay, Enos speculates on a world of radical coexistence in which human and nonhuman agencies coalesce to sustain life anew.

Hiroshima-based artist Sakura Koretsune’s After Efflorescence: Awakening the Whale Beneath Us (2025) traces the intertwined relationship between cetaceans and humans from prehistory to the present, notably within the context of Aichi prefecture. Recalling forgotten uses of whale bones and organs in tools, ceramics, and postwar survival, her project transitions layered research into an embodied experience. Skeletal fragments, clay pipes, and bone-shaped ceramics are placed beneath suspended translucent fabric sheets embroidered with images of a whale’s cross-section, inviting viewers into a bodily passage through history. Rui Sasaki’s Unforgettable Residues (2025) deepens this meditation on nature and time, drawing on seasonal research of local plants. Installed in Seto City’s former Nihon Kosen bathhouse, her glowing glass tablets encase local plants—historically consumed to fire kilns—that have been reduced to ash, crystallizing their lingering spirits. Reflective and transparent, the glass holds the tension between extraction and preservation, revealing traces of life as well as our own mirrored images caught in the act of remembering.

In this edition of the triennale, ceramics form a locus for practices spanning generations and cultures, with the Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum acting not only as a physical venue but also as a kind of kiln for reimagining the human-earth relationship. This spectrum includes Wangechi Mutu’s Sleeping Serpent (2014–2025), a nine-and-a-half-meter-long creature with a bulging belly and human head that slithers through East African myths, futuristic imaginings, and histories of violence inflicted upon the Black female body. In contrast, Izumi Kato’s untitled action-figure scale sculptures envision primordial life, exploring human-marine hybridity in dialogue with vessel fragments from the museum’s collection.

Through the medium of ceramics, time thickens—linking the ancestral, the geological, and the human. Yasmin Smith’s wall-mounted Forest (2022), resembling geological specimens, reveals layers of deep time disrupted by extractive human activity. Cast from coal lumps mined around Sydney and glazed with fly ash from power stations along Australia’s eastern seaboard, each piece varies subtly in hue and texture. Meanwhile, a backdrop painted with Nagoya coal ash further extends a dialogue with materials condensed over millennia. Kyoto-based Akane Saijo’s The Pomegranate of Sisyphus (2025) transforms ceramics into a performative medium, restoring its corporeal origins. Her pomegranate-inspired sculptures, which serve as allegories of local labor, feature mouth-like openings that invite skin-to-skin contact during accompanying performances, rekindling intimacy with the earth and reimagining ceramics as living, relational bodies.

Newly commissioned site-specific works expand the exhibition’s material sensibility, immersing viewers in spaces where the real and virtual intertwine. Argentine artist Adrián Villar Rojas transforms the abandoned Former Seto Fukagawa Elementary School with Terrestrial Poems (2025), enveloping its classrooms and corridors in printed sheets that merge cave paintings, early human simulations, and digital glitches into a single continuum—a speculative cave of our time where prehistory and post-digital futures coexist within a vacant educational ruin reflective of East Asia’s declining birth rates. Meanwhile, Korean artist Kwon Byungjun, a pioneer of mechanical theatre, transforms the grassy field of the Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum into a polyphonic landscape with Speak Slowly and It Will Become a Song (2025). His GPS- and sensor-based soundscape captures the sounds of the earth, folk songs, and ambient noise, reacting to the subtlest movements. Listeners are guided off predetermined paths, invited to wander through the greenery, chasing voices that merge human and nonhuman resonance. The headphone-clad bodies drifting across the field form an open-air sonic sculpture—a living choreography of attunement.

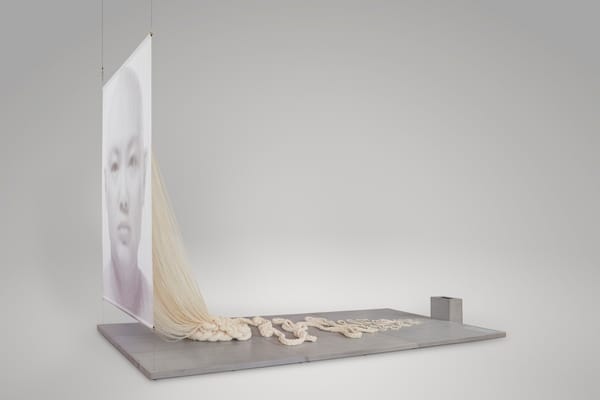

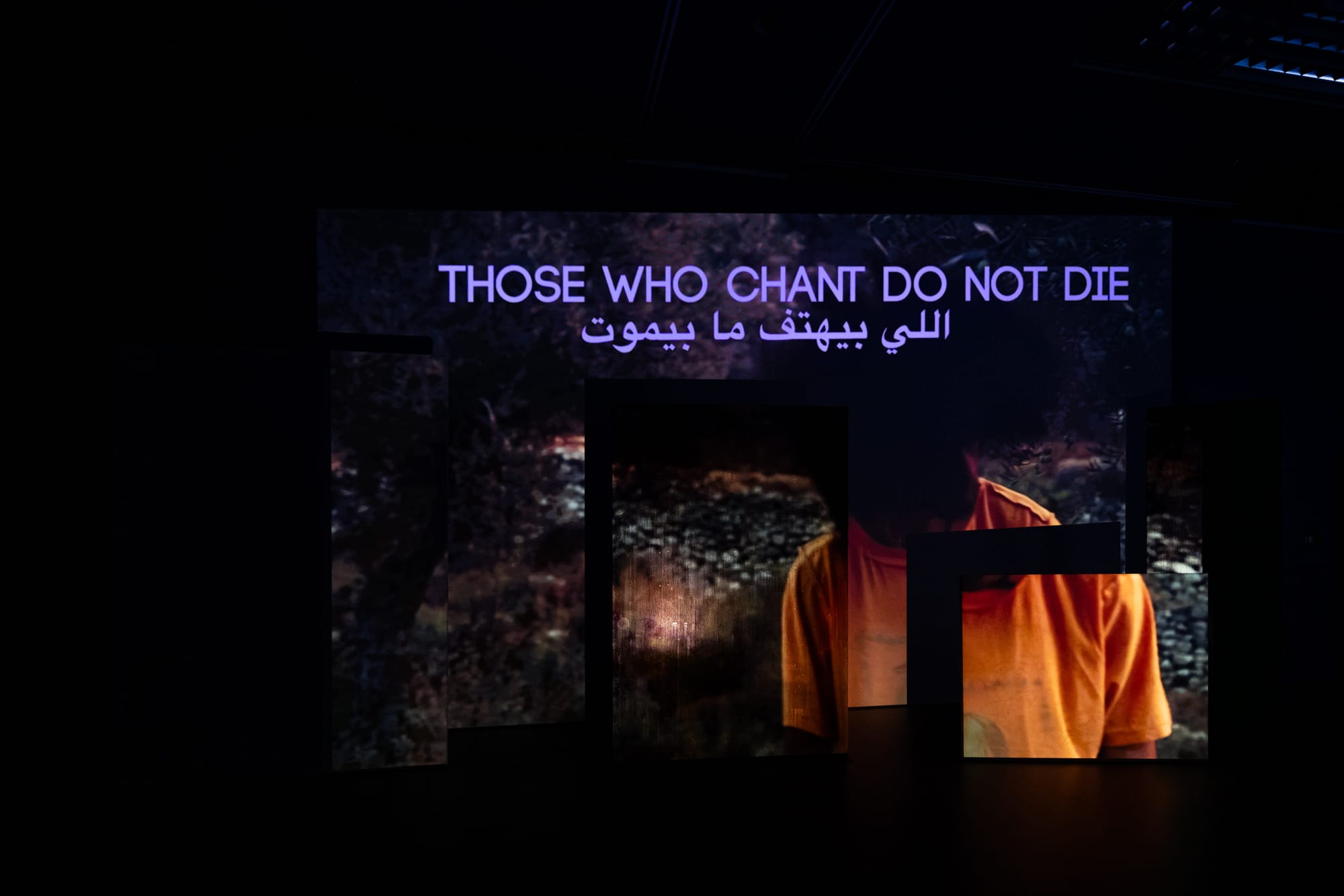

Extending the exhibition’s theme of renewal, a focus on collective forms of making and being reveals solidarity as a medium of survival and hope. The Korean collective ikkibawiKrrr examines village culture as an endangered practice in today’s hyper-individualized society. In kkik (2025), they capture the quiet rhythms of everyday gatherings and aged objects throughout a local kissaten—a traditional Japanese coffeehouse. They also join the Hashinoshita Center community in O, Open the Door, I Pray (2025), a collective dance that fuses Japanese and Korean folk movements with punk music and festival energy, creating an act of solidarity that welcomes bodies of different capacities. A similar pulse of shared endurance animates Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme’s May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth: Only sounds that tremble through us (2020–22), which floods the space with fragments of song, dance, and everyday life from Palestine, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. Projected onto concrete walls that evoke architectures of separation, the work becomes a communal rhythm where music and bodies persist against displacement, reclaiming not only survival but abundance and joy.

Attuned to local voices while resonating across borders, the triennale restores the biennale framework—often critiqued for its detachment from lived realities—as a space of solidarity where diverse histories and urgencies converge through shared gestures of renewal. Rooted in the soil of Aichi yet reaching outward in dialogue, “A Time Between Ashes and Roses” unfolds not merely as a presentation but as a collective inhabitation amid ongoing crisis, where gathering itself becomes a fragile yet enduring act of hope.

Jiwon Yu is a curator, writer, and translator mainly based in Seoul.