Shows

Accelerated Dreams: Interview with Ayoung Kim

Ayoung Kim navigates the accelerated rhythms of contemporary life through multimedia works that blur gaming, cinema, and reality. Her ongoing series Delivery Dancers, featuring the recurring character Ernst Mo racing through neon-lit cityscapes, examines technoprecarity and the gig economy’s relentless optimization. After receiving the 2024 ACC Future Prize and 2025 LG Guggenheim Award, Kim made her solo debut in Europe with “Many Worlds Over” at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof this February, and will open a major solo presentation at New York’s MoMA PS1 later this year.

Drawing on 1980s and ‘90s Hong Kong action cinema, Dancer in the Mirror Field (2025)—the latest iteration of Kim’s Delivery Dancers series—debuted on the waterfront M+ Facade in Hong Kong on October 3. Ahead of the commission’s unveiling, Kim spoke to ArtAsiaPacific about creating female-to-female action sequences against the backdrop of Hong Kong’s skyline, the unexpected complexities of gig economy labor, and the radical shifts in how technology shapes our perception of time and space.

When you imagine Dancer in the Mirror Field being screened on the M+ Facade, what do you most hope a passerby will feel or question after glancing up at it—close up or from afar—even for a fleeting moment?

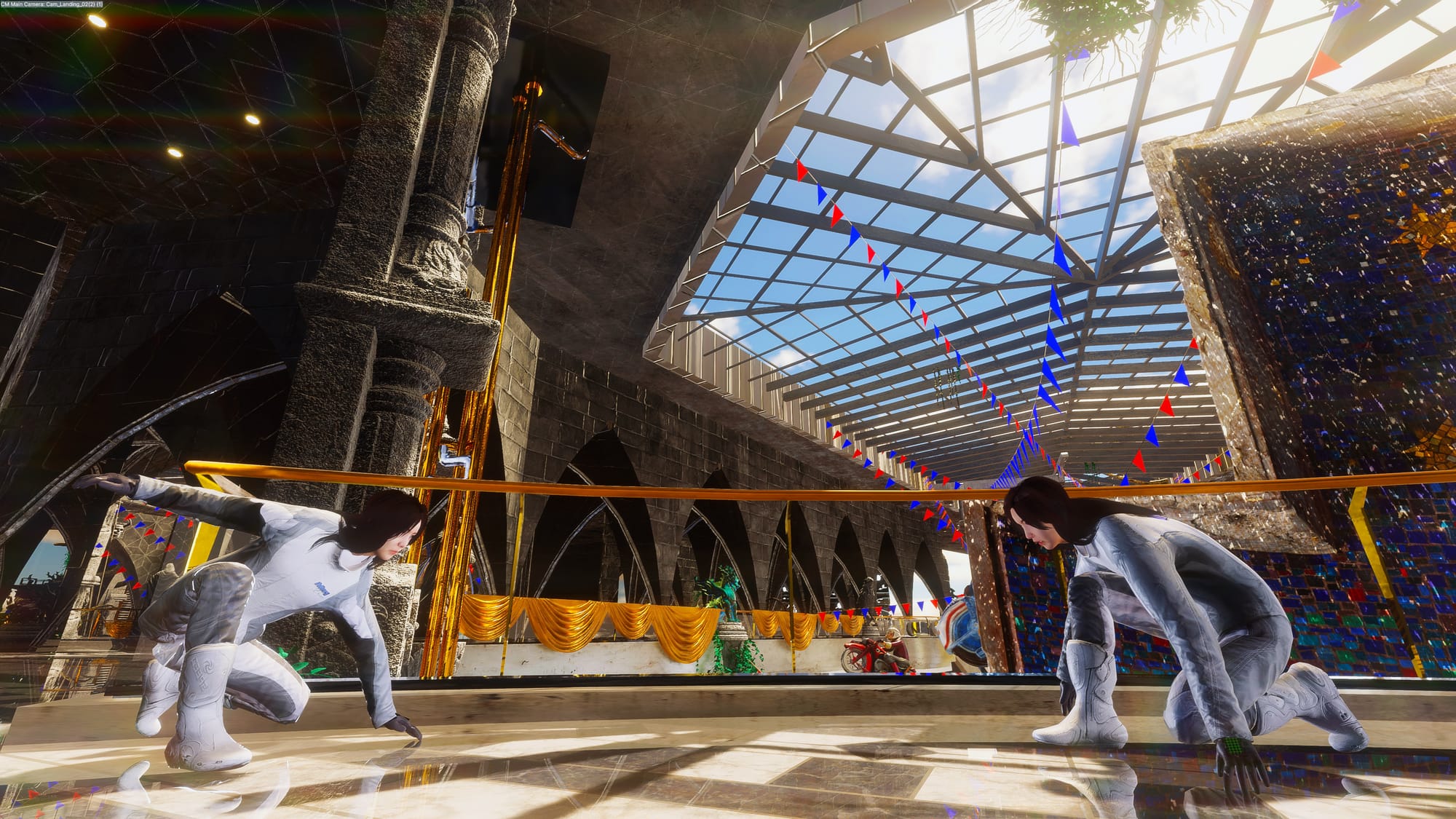

The M+ Facade is a very specific place. Rather than an exhibition gallery or screening room, it’s an exposed environment and part of the skyline. Random people will encounter it while commuting on the ferry or passing along the Harbor, and many have seen the different M+ Facade commissions. For my version, I thought it would be interesting to show a dynamic female-to-female action sequence against the backdrop of the city’s skyline—many of the scenes directly reference Hong Kong’s action cinema from the ‘80s and ‘90s. I wanted to blend those elements with a 21st-century aesthetic that incorporates game engine technology and generative AI.

When you first conceived the character of Ernst Mo, did you always intend for her to be a recurring figure? Did you have a specific narrative planned for her from the outset, or has her story evolved more organically over time?

I think it’s the latter. I never start a project with the intention of making it into a series, but eventually, I end up having many ideas about this character or this world, so I might create smaller episodes as a side story or spin-off. It has been three years since I kicked off the Delivery Dancers series, and it’s still going strong across so many different platforms—video, multichannel video, game simulation, this facade project. And get this, it’s going to be a live motion capture performance for the Performa Biennial in New York next month!

I have a strong feeling that this facade project and its world-building could easily expand into a simple game, offering diverse transmedia narrative possibilities. This is largely due to the nature of game engines. Once elements are built within them, they can be readily utilized for various purposes—interactive media, VR, or game simulations—because the foundational assets are already established. I believe this aligns perfectly with current game engine developments, enabling a surge in visible transmedia narratives.

What places, sensations, or memories of Hong Kong personally helped you shape the neon-lit cityscape of this chapter in your Delivery Dancers series?

It’s futuristic and nostalgic all at once, packed with diverse temporalities. Dancer in the Mirror Field is structured in three chapters. Chapter one features a strange, abandoned Asian-type mall. Chapter two is a Hong Kong street scene, referencing the ‘80s and ‘90s with its vibrant optics that also feel futuristic, as you remarked. The third chapter returns to the mall, but it’s visually disrupted, chaotic, with many elements floating and inverted.

Last year, a research trip to Hong Kong proved invaluable. With the assistance of curators at M+, I explored numerous malls featured in ‘80s Hong Kong action cinema as well as street marketplaces and alleyways, all of which provided rich visual aesthetics for the game engine world-building. The Cityplaza mall in Tai Koo Shing, for example, which is notably featured in the pivotal action film Long Arm of the Law (1984), offered an iconic scene: an assassination involving a jump and fall from the fourth floor onto an ice rink, complete with sprays of blood. The camera work and editing in that sequence were particularly striking. I discovered a recurring architectural element in many labyrinthine Asian-type malls across Hong Kong: a central area featuring either an ice rink or a cinema.

For Dancer in the Mirror Field, I wanted to emulate this action-acrobatic sequence for the 3D characters. This time, there are three versions of Ernst Mo—previous iterations had one or two—who must race to win a peculiar contest run by the Delivery Dancers Company called the “Dancer of the Year.” Each year, a top winner is chosen and applauded, but the purpose of the competition remains unclear. The contestants bend the rules to break free, sprinting, fighting, and executing high-stakes, public-facing sequences, as if they have been brainwashed. It stays intense but is crafted for a broad audience. To ensure it reads clearly on the screen, we collaborated with an action choreographer to create precise, female-to-female exchanges.

Your work centers around a delivery rider in a surreal race. What drew you to the idea of labor, optimization, and self-competition in your work?

The contemporary world, particularly post-pandemic, has seen an acceleration of platform, precarious, and gig labor. I am particularly interested in the term “technoprecarity,” as uncertainty has become our general condition in the 21st century.

While interviewing a highly experienced and professional female delivery rider in Korea, I gained considerable insight by observing her work firsthand. Riding on the back of her motorbike as she navigated the city, I experienced her daily reality. This provided a deep understanding of the physical and mental relationship riders have with their apps. The constant stream of signals and alarms—offers, calls, decisions to accept or decline—demands constant interaction, all while monitoring a separate navigation app and the physical road ahead. This creates a state of bifurcated or multiplied realities, obviously dangerous and requiring intense focus. It’s an unstable and harsh job, as they are freelancers unprotected by employment law, a harsh reality for them.

Interestingly, my recent interview with someone working in a logistics center, a packaging job, challenged my assumptions. Many people in the gig economy expressed satisfaction with their work, which countered my initial hypothesis and led me to think deeply about the nature of work today. If people are content with these conditions, then what is the actual problem? Perhaps this precarity is simply part of the general condition now.

Self-competition—speed, velocity, and productivity—is the anthem of our contemporary world. Neoliberal capitalism relentlessly demands we be productive. In South Korea, especially in Seoul, this pressure is palpable, like the very air you breathe—you can’t escape it. I imagine Hong Kong is similar. Every industry, even the art world, feels like an extreme survival game. This high societal acceleration is intense. I don’t know if a breakthrough is feasible, but as an individual artist, I can’t offer any direct solutions. My approach is to explore these themes within my practice, and self-competition is a key element I grapple with.

Has your understanding of optimization algorithms and the gig economy shifted at all through the making of this film?

I think so, in a way. Whenever I use delivery apps—which I still do—I automatically start considering how they route the riders. Similarly, when I log on or off of certain apps, I find myself pondering the behind-the-scenes operations. While it’s impossible to fully grasp the black box of all this technology, I do begin to think about it, even if just a little.

Your facade project also highlights fragments of real objects from the M+ and Powerhouse collections. What was your process for selecting these items, and what function do they serve within the narrative of the work?

Powerhouse, a museum of applied arts and everyday objects, has an extensive database that its staff can query like a search engine. Our initial search of their database was very broad, yielding many wonderful and eye-opening objects from toys to a mosaic mural, but also overwhelming due to the breadth of their collections. We selected a few from their catalogue and requested 3D scans of the data. They kindly provided these scans, which we’ve been able to use as backdrops and triggering objects, regardless of their varying quality.

In the first shopping mall scene, the arena features blown-up, balloon-like bike racing toys that serve as decorative elements. Additionally, posters from the Powerhouse Museum—promoting psychedelic music and rave parties—contribute to the overall look and feel.

M+ provided the iconic Hong Kong neon sign “Sammy’s Kitchen” for the street scene. Zaha Hadid’s early acrylic painting of an unrealized Hong Kong culture club, and Rirkrit Tiravanija and Navin Rawanchaikul’s collaborative drawing of the Bangkok cityscape were also integrated as backdrops. Teenage Engineering contributed a detailed 3D model of their compact sampler “PO33! K.O.,” reminiscent of a game pad, which triggers elements related to the narrative.

When technology is both a tool and a theme, how do you decide where to let it lead—and where do you question its presence in your work?

I enjoy experimenting with new technologies to uncover their hidden potential. Technologies initially possess latent qualities that can be developed, redirected, or diversified. An artist’s role, as I see it, is to challenge a technology’s singular definition or utility, offering new pathways. This process often reveals a technology’s concealed capacity, even if its immediate practical value is minimal, and it’s this exploration that drives my visual storytelling.

My recent projects are deeply concerned with technoprecarity and its pervasive side effects on our daily lives. It's the reshaping of our lives by these effects, rather than technology itself, that forms the core of my practice.

Before the platform and smartphone era, our perception of temporality wasn’t as magnified. We now operate on a minute-by-minute schedule, a stark contrast to the past, when navigating required printed maps like an A-to-Z. In the early 2000s, I could barely visit three places a day due to the logistics of maps and addresses. Now, we can accomplish so much more in a single day—multiple meetings, numerous tasks. This radical change in our sense of time, which can lead to significant fatigue, is a direct effect of technology.

My exploration of navigation, particularly in the pre-GPS era, led me to research traditional calendar systems and celestial wayfinding. I discovered a striking contrast: premodern peoples navigated and marked time by observing the stars above. Now, our primary tool for navigation and timekeeping is the mobile phone, held downward. This radical shift from “above” to “below” means a lot, I think.