People

The Essential Works of Lionel Wendt

Born in 1900 in Colombo, Lionel Wendt was a leading cultural figure in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) who established himself as a photographer, pianist, newspaper columnist, and art critic. A forerunner of avant-garde photography in Asia, his oeuvre ranged from portraiture and nude studies to landscapes, still lifes, and documentary-style works, all imprinted with his distinctive style and mastery of technique.

Wendt was active at a liminal period in Sri Lanka’s history, as the country stood at the threshold of independence (to be granted in 1948) after over 400 years of Portuguese, Dutch, and then British colonial rule. The search for a renewed sense of national identity was an urgent—and often contentious—issue that Wendt explored through the lens of his own complex heritage: though Ceylonese himself, he hailed from the mixed-race, dominant Burgher minority, descended from European settlers. He enjoyed a privileged upbringing with a Western education, having studied law in London and trained as a concert pianist at the Royal Academy of Music, before dedicating himself to photography in the 1930s. Yet he was also a social outlier by reason of his sexual orientation—being gay was not merely taboo at the time, but strictly illegal. Wendt’s queerness manifested in his photography through an overarching study of the male body, his focus implicitly revealing that which could not be spoken.

At the same time, Wendt was not a complete outsider—he had a strong sense of belonging and possessed a broad knowledge of the culture and traditions of his native Ceylon. Spanning the 12 years between 1932 and his early death in 1944, his short-lived yet prolific photographic career gave rise to a wide-ranging, beautifully rendered body of work featuring a distinctive blend of pictorialist and modernist sensibilities. His search for identity was as much personal as it was national, endowing his work with multifaceted interpretations.

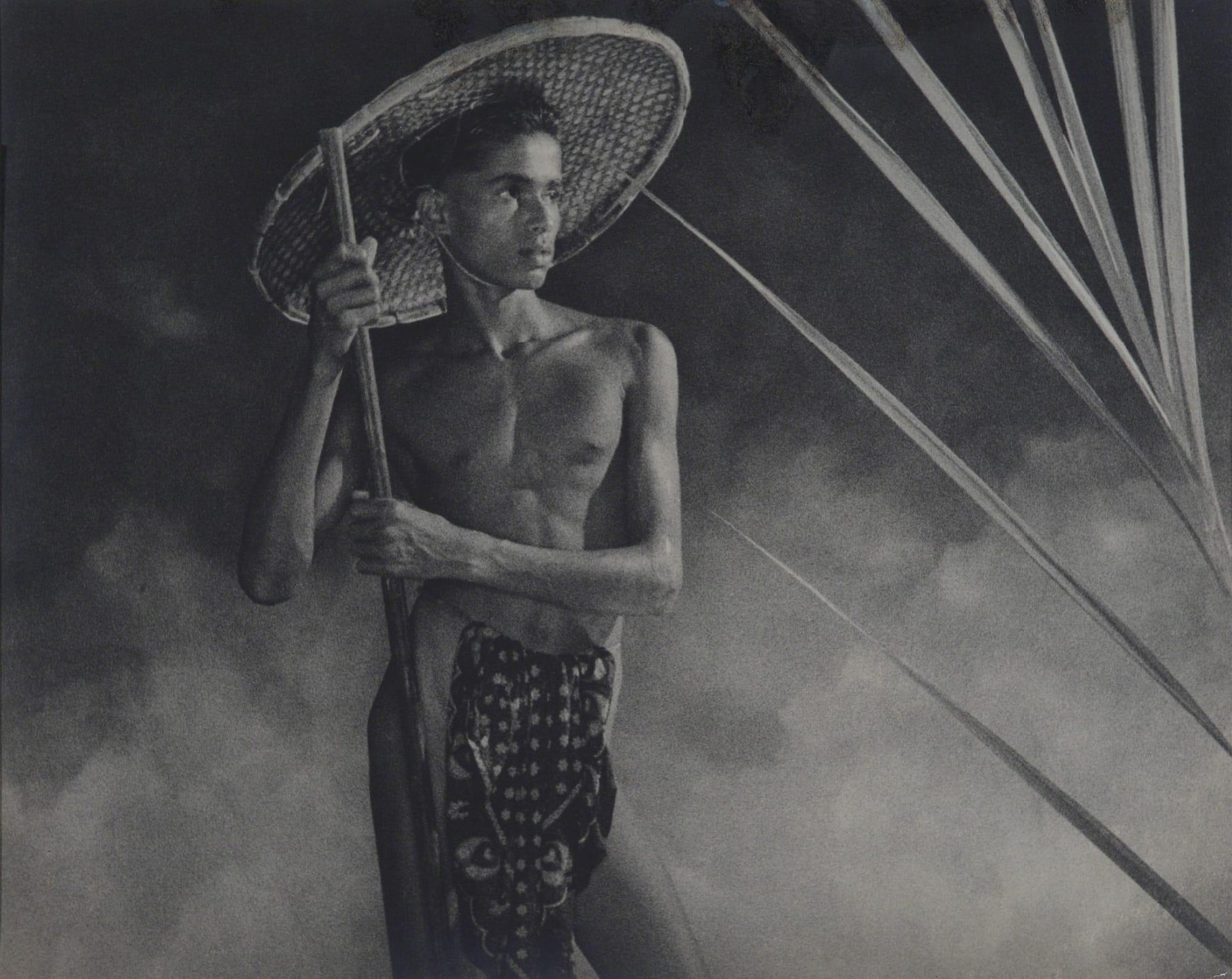

Untitled (Goviya-V) (c.1934–35)

Wendt’s Untitled (Goviya-V) (c.1934–35) is part of a small series centered on rice farmers (Goviya in Sinhala). On the surface, these staged images read as exoticized ethnographic studies, a genre analogous to the Western colonial gaze (think Paul Gauguin’s paintings of Tahiti). The male nude was certainly one of Wendt’s most recurring subjects; however, further reflection reveals an underlying subtext. The painted misty backdrop, the moody lighting, the classic pose, and the use of props—all of these elements serve to emphasize rather than conceal the theatricality of the image. This is done to such a degree that the photograph resembles a film still or a melancholic scene from a stage production. Moreover, the chosen subject is not arbitrary, but politically charged, as Wendt references the Govigama caste, who were associated with traditional rice cultivation for centuries under the Rājākariya system. This was abolished by the British colonial administration in 1832 and replaced by a more centralized plantation model. For his Ceylonese audience, this image was intended to evoke a sense of nostalgia for a precolonial past, simultaneously challenging British settler agriculture and its practices of enclosure and extraction. Through referencing a historic example of sustainable, self-reliant living—even if heavily romanticized—the image also looks to the future, as echoed by the subject’s wistful yet steadfast gaze to a far-off horizon.

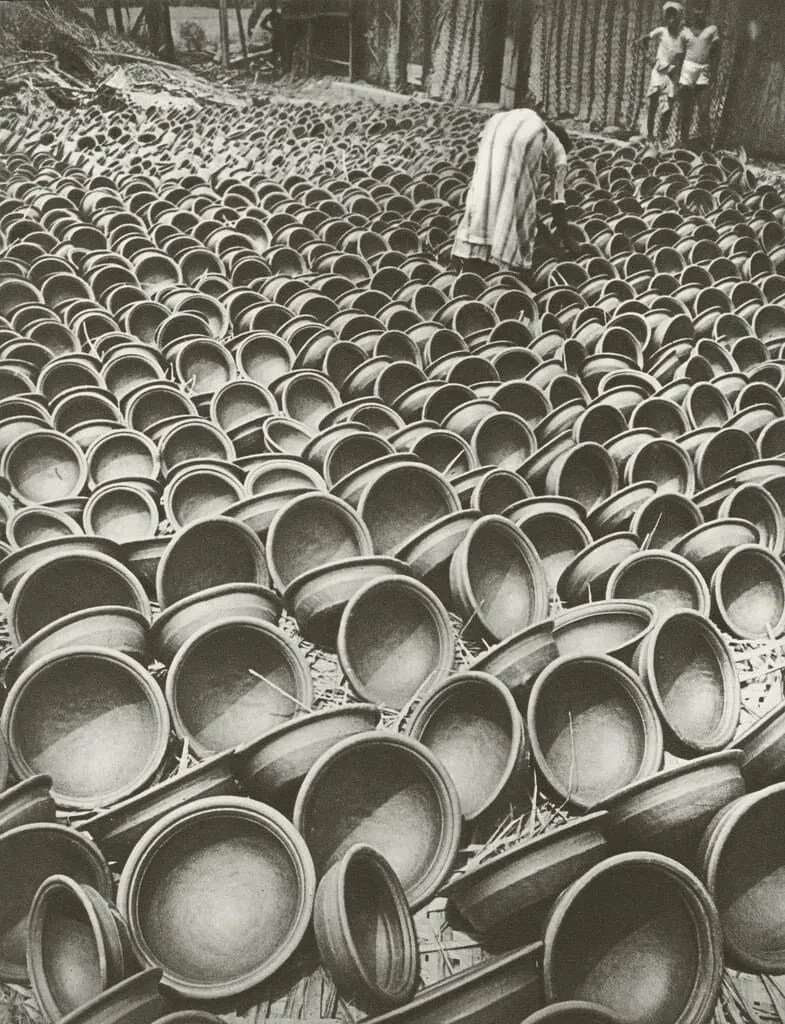

At the Pottery (c.1937)

At the Pottery (c.1937) is an example of Wendt’s more straightforward, documentary-style work. His early adoption of the more compact and portable Leica rangefinder gave him the freedom to move outside the studio and shoot scenes from across the island. His series focusing on Ceylon’s rural industry is the highlight of this collection. At the Pottery demonstrates Wendt’s modernist approach to composition, using cropping, lighting, and perspective to show commonplace objects—in this case, bowls—from an unusual vantage point. The photograph brings to mind the work of his North American counterparts and their images of industrialized mass production, while remaining unequivocally grounded in the localized context of his homeland. Take Margaret Bourke-White’s photograph Delman Shoes (1933), which bears a striking likeness to At the Pottery, but zeroes in on shoes instead of bowls. However, while Bourke-White’s picture emphasizes the issue of overproduction and underconsumption in the US during the Great Depression, Wendt’s image is a celebration of abundance. Handcrafted and locally made, the bowls are in diametric opposition to machine manufacturing. The photograph adds to the premise of Ceylon’s self-sufficiency and industriousness, while also underlining the country’s natural abundance: running themes in his work that aimed to bolster Ceylon’s movement toward independence.

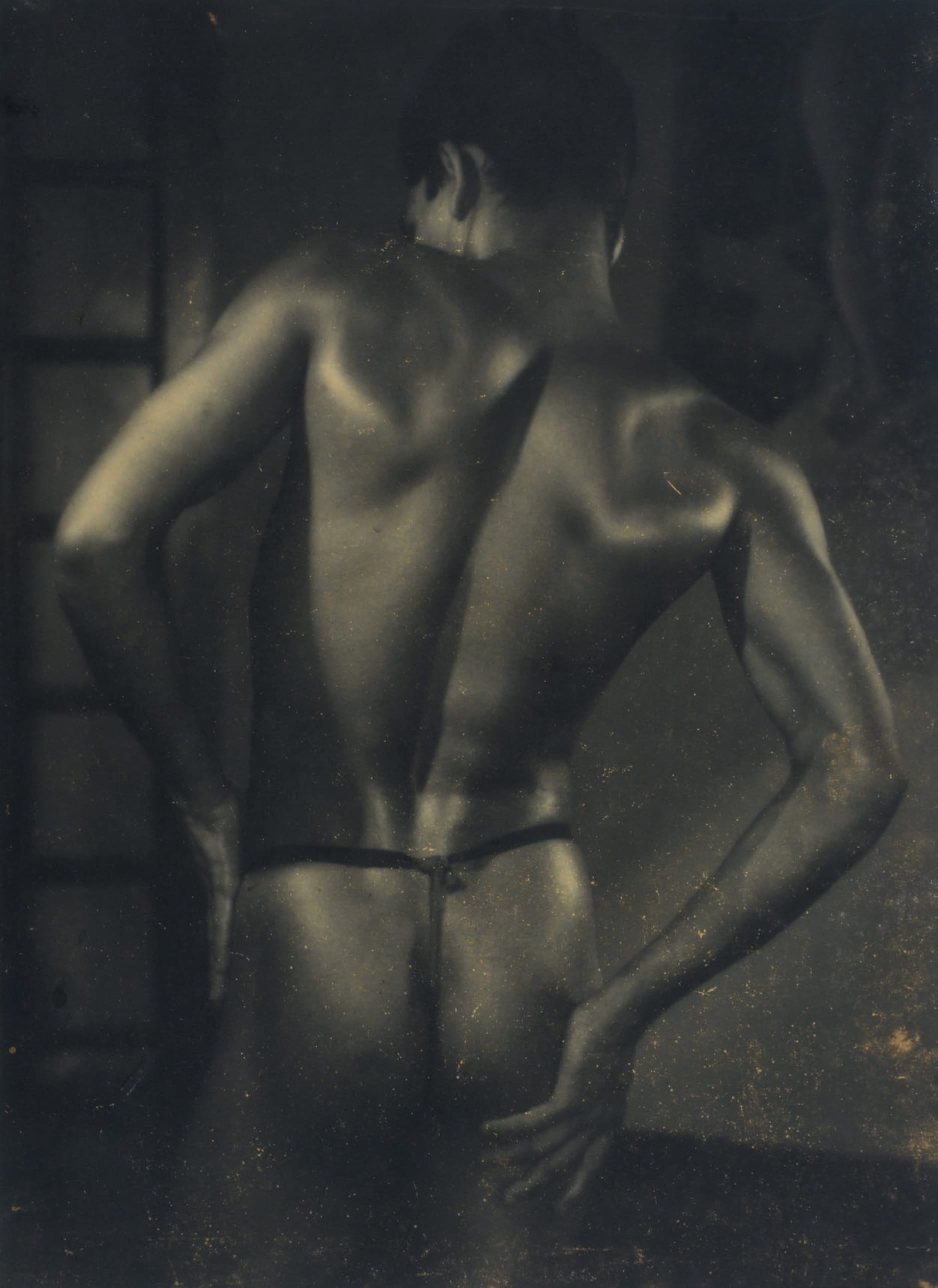

Back of a Youth (c.1934–40)

Among Wendt’s entire back catalog, there is one group of images that stand out, both in terms of sheer quantity and pure visual presence: his sensual, homoerotic nudes. In a time and place where queerness was outlawed, these photographs are unblushingly defiant, and as beautiful as they are brazen. Still, Wendt just barely managed to stay within the bounds of decency: his subjects don traditional Ceylonese loincloths and assume elegant poses, contriving an overall quality of a classical nude or ethnographic study. However, most of these works remained in Wendt’s private collection and were never publicly exhibited. Back of a Youth (c.1934–40) is one of the better-known photographs from this series, the bold composition and tight crop putting the male subject front and center. Here, Wendt’s deft use of studio lighting mirrors the chiaroscuro of classical paintings and sculpture, gently illuminating the subject’s back to reveal tensed muscles under smooth, bronze-like skin before sinking into inky blacks. This effect is heightened by Wendt’s considerable darkroom skills, which allowed him to further push the heavy, shadowy rendering of the print. These boundary-pushing photographs have attracted their fair share of criticism, with Wendt’s barely suppressed desire submitting to a sexualized, othering gaze.

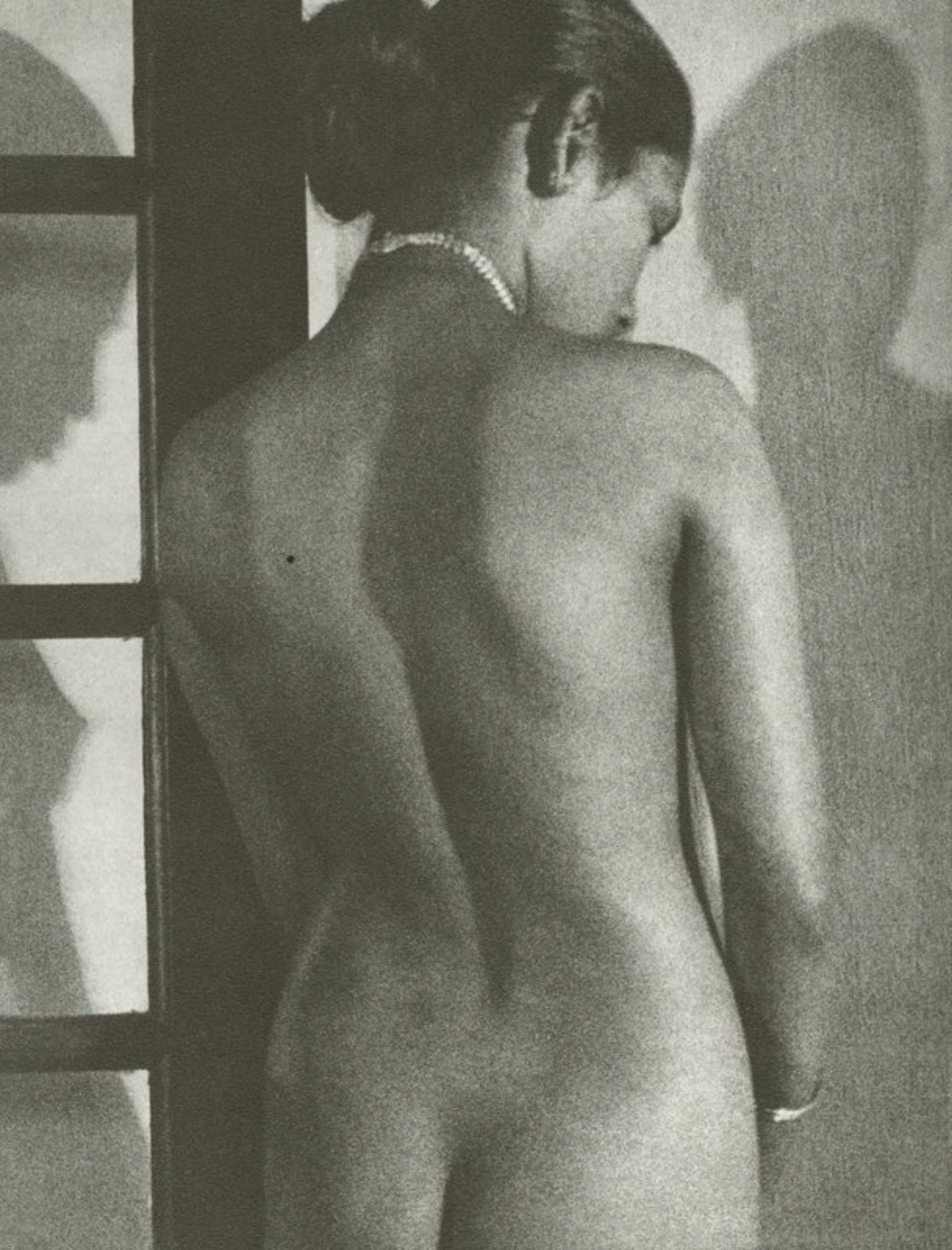

Nude (c.1932–44)

A perfect counter to Wendt’s erotically charged male studies can be found in his female nudes, which are rendered very differently. Gone are the dark contours and glistening bodies—instead, these images are marked by a very delicate, sensitive touch. Compositionally, Nude (c.1932–44) is similar to Back of a Youth, with its tight crop and pose of the subject, whose back is turned to the viewer, her head lowered and face hidden. In Nude, however, the woman’s posture is much more relaxed. The contrast between light and dark continues to play an important role here, but the focus lies on the cast shadows, rather than the chiaroscuro. Most evocative is the shadow to the left, which lays bare the subject’s profile and the graceful curve of a breast, divided by the panels of a sliding screen door. This composition is balanced symmetrically by a second shadow to the right. The soft, slightly grainy quality of the print comes from Wendt’s use of the bromoil process: a darkroom technique that was popular among pictorialists for its unique texture and tonality.

Still Life on Balcony / Statuette Among Leaves (c.1934–38)

Further underscoring Wendt’s prowess in the darkroom are his series of more experimental works, for which he employed various techniques: photomontage, reversal, solarization, and even the photogram. What makes Still Life on Balcony / Statuette Among Leaves (c.1934–38) stand out is Wendt’s combined application of multiple techniques on a single print. This photograph debuted in Leica News and Technique No. 32, 1938, in an article titled “‘Solarisation,’ or Partial Reversal,” which was also the first published instruction on the process. In this issue, Wendt notes how his initial interest in solarization was sparked by the work of Man Ray, who first developed the technique alongside Lee Miller, his assistant at the time. Through much experimentation, Wendt devised his own approach. Leica also sponsored Wendt’s first solo show, an “Exhibition of Leica Photographs by Lionel Wendt, Ceylon,” held in London that same year. The statuette appears to be a South Asian Buddhist relief carving, similar to those documented by Wendt in his photographs of Ceylonese religious sites, providing an intriguing parallel to his nude photography.

Strange Décor (c.1933–34)

This seemingly ordinary sea and landscape photomontage is peculiar for a number of reasons. Firstly, it differs considerably from Wendt’s more prosaic beach scenes and other landscape works. The structured composition, as well as the strange juxtaposition of disparate objects, give the photograph a surreal quality. The frame is neatly divided into four equal quarters—divided lengthwise by the horizon and, vertically, by a rather forlorn telegraph station. In the top right quadrant sits an 18th-century brig, presumably anchored, sails furled. The pier is similarly lifeless, save for an oddly out-of-place goat toward the bottom left. The scene carries an air of abandonment, perhaps signifying a vanishing age of colonialism, tinged with an introspective melancholy—Wendt’s lineage, after all, made him a direct descendant of these settlers. On the very bottom right, however, lies a booklet titled Shaw on Stalin: a 1941 publication by George Bernard Shaw, controversially extolling the virtues of Stalin’s Soviet Union. Wendt was a vocal advocate of socialism, no doubt suggesting a way forward for his country.

On December 19, 1944, Wendt passed away at the age of 44 from a heart attack, never witnessing the independence of his homeland or its tumultuous postcolonial struggles, including a decades-long civil war. Despite his considerable fame at the time, his work slowly faded into obscurity until the rediscovery of his prints in 1994 generated a brief revival of interest. Although Wendt’s works are now housed in numerous important collections, he remains largely underexposed, even within Sri Lanka. Moreover, despite writing substantially about the works of other artists, he left very little documentation of his own oeuvre. There is, however, one short passage written by Wendt in the foreword of the 1938 Observer Pictorial, which aligns with his own photography quite seamlessly: “Here you will find much that is beautiful and significant in Ceylon life—men and women, the daily round, the Perahera, serene landscapes, the spirit of the past, the realities of the present, and something of the promise of the future . . . phrases, as it were, from a song of Ceylon—things that the people of the country should cherish.”

Iain Cocks is an editorial intern at ArtAsiaPacific.