Market

Tokyo’s Autumnal Best at Art Week Tokyo 2025

Art Week Tokyo (AWT) 2025 kicked off amid a busy autumn calendar, nestled between major Japanese art events like the Aichi Triennale, the Setouchi Triennale, and the Okayama Art Summit, as well as regional fixtures such as the Taipei Biennial and Shanghai’s art fairs. Launched in November 2021 during the Covid-19 pandemic and its travel restrictions, the event’s international ambitions have since been amplified. This drive is further propelled by its collaboration with Art Basel, attracting a global network of collectors and curators, and bolstered by support from Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs.

Shunichi Tokura, the agency’s commissioner, welcomed visitors to Tokyo at the opening ceremony on November 4. The historic Okura Tokyo, a long-time host to global dignitaries (including US President Trump just days prior), served as the central hub. From here, art lovers boarded free, hop-on, hop-off, shuttle buses connecting 53 participating institutions, galleries, and art spaces across the city. Staff distributed complimentary wristbands at each stop, underscoring the organizers’ priority of public access to art.

At the helm of AWT is gallerist Atsuko Ninagawa of Take Ninagawa, and together with AWT’s editorial director Andrew Maerkle, the event offers both local and international perspectives. This is exemplified by the appointment of Adam Szymczyk, artistic director of documenta 14 and former director and chief curator of Kunsthalle Basel, to curate the AWT Focus exhibition. Housed in the historic Okura Museum of Art on the hotel grounds, Szymczyk’s exhibition “What Is Real?” featured over 100 works by 60 Japanese and international artists from the rosters of participating galleries. The show explored the loss of reality and sense of belonging in turbulent times—a poignant theme given the museum’s location opposite the US embassy and residence.

Tokyo’s institutions presented impressive exhibitions, showcasing the breadth of Japanese art and hinting at exciting future trajectories. The National Art Center, Tokyo’s exhibition, “Prism of the Real: Making Art in Japan 1989-2010,” co-curated by NACT’s Yukie Kamiya and Doryun Chong from M+ in Hong Kong, focused on the pivotal period spanning the early Heisei era, the end of the Cold War, and Japan’s “bubble” economy up to the early 2000s. This era marked a significant shift as Japanese artists began gaining international recognition through major biennales and exhibitions. A highlight included archival footage of foreign artists like Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Nam June Paik, Joseph Beuys, Daniel Buren, and Anselm Kiefer visiting, working, and sometimes collaborating in Japan, capturing the nation at the cusp of globalization. The exhibition concluded with contemporary explorations of identity and community, reflecting on individuals’ place within modern society.

This was also the focus of 2023 Calder Prize winner Aki Sasamoto’s midcareer survey, “Life Laboratory,” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. Born in 1980 in Kanagawa, Japan, Sasamoto studied and continues to work in New York, utilizing multiple mediums to express her ideas. In the site-specific performance, Spirits Cubed (2020), Sasamoto appeared in a large room with its walls painted black and with materials left behind after a building renovation, deliberately installed in a whimsical fashion. Originally a site-specific intervention for Japan’s Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art, the Tokyo edition featured glass windowpanes, ladders, trolleys, and metallic air-conditioning ducts hanging from the ceiling and sprawling across the ground. These channeled wind into glass orbs containing drinking glasses, causing them to spin in a centrifugal fashion. Sasamoto herself drew weather notations onto a plexiglass panel—from wind barbs, isobars, and other symbols from a synoptic chart—while she intermittently sprinted across the room and into the audience. She created sound by forcefully pulling a large plastic bag overhead and trapping air, and whipping the air-conditioning ducts, dragging them across the floor. Sasamoto sees these objects as forming pathways for spirits, perhaps propelled by the wind and other natural, kinetic forces.

Nearby, at the Mori Art Museum, perched atop a Roppongi skyscraper, Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto’s monographic exhibition, “Primordial Future Forest,” offered an appropriate setting for his visionary designs. Fujimoto’s titular work, Forest of Future, Forest of Primordial – Resonant City 2025, imagines a literal city in the sky above Tokyo Bay. This concept features flying vehicles powered by renewable energy traversing a metropolis composed of latticed spherical structures, each a quarter-mile in diameter. These structures house all necessary urban functions and facilities, reflecting Fujimoto’s belief that digital technologies like artificial intelligence and augmented reality will not diminish the value of physical space.

Fujimoto gained prominence after his Aomori Museum of Art Design Competition proposal in 2000, where he had been influenced by Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Running Fence (1972–76). He perceived this work as blurring the lines between architecture and nature, a concept echoed in his proposal’s integration of the surrounding forest of the museum. A Serpentine Pavilion alumnus, Fujimoto most recently designed the Grand Ring for Expo 2025 on the man-made island of Yumeshima. An imposing to-scale model of this structure was featured within the Mori. However, the exhibition’s highlight was at its outset: hundreds of architectural models and prototypes, displayed waist-high, filled the hall. Navigating this dense arrangement of maquettes, each requiring quiet observation and contemplation, proved a challenging yet rewarding experience. Curator Reiko Tsubaki noted that Fujimoto intended for visitors to engage closely with his work, evidenced by the exhibition’s early closure every Tuesday to allow for the studio’s careful restoration of pieces damaged by visitor interaction—whether snagged by clothing or knocked by elbows or backpacks.

Tokyo’s galleries are scattered across the sprawling city, which necessitated shuttle buses to transport visitors. Across town, within the Terrada Art Complex, the gallery Anomaly hosted Chim↑Pom’s exhibition, “A Hole within a Hole within a Hole,” showcasing several of the Japanese art collective’s signature tongue-in-cheek works. Inspired by urban infrastructure voids like manholes and sewers, and their associated waste, the show featured Asshole of Tokyo (2018), a video work presented within a replica of a manhole cover. Another piece, Akataro (2024), incorporated actual dead skin collected from various artists, including French photographer JR, alongside microscopic images of the samples.

Chim↑Pom’s two-minute film, K-I-S-S-I-N-G (2011), was a crowdpleaser at AWT’s film platform curated by Keiko Okamura and housed in the lobby of the SMBC East Tower. The film depicted two illuminated lightbulbs with faces, intertwined in a kiss, before smashing into each other. Also featured was Okinawan artist Chikako Yamashiro’s Okinawa Graveyard Club (2004), where she dances and gyrates to disco music before traditional hakaniwa tombs. Yamashiro was further highlighted in an expansive double-bill exhibition at the Artizon Museum, “Jam Session: The Ishibashi Foundation Collection x YAMASHIRO Chikako x SHIGA Lieko – In the midst of,” where she, along with Lieko Shiga, selected artworks from the foundation’s collection to be in dialogue.

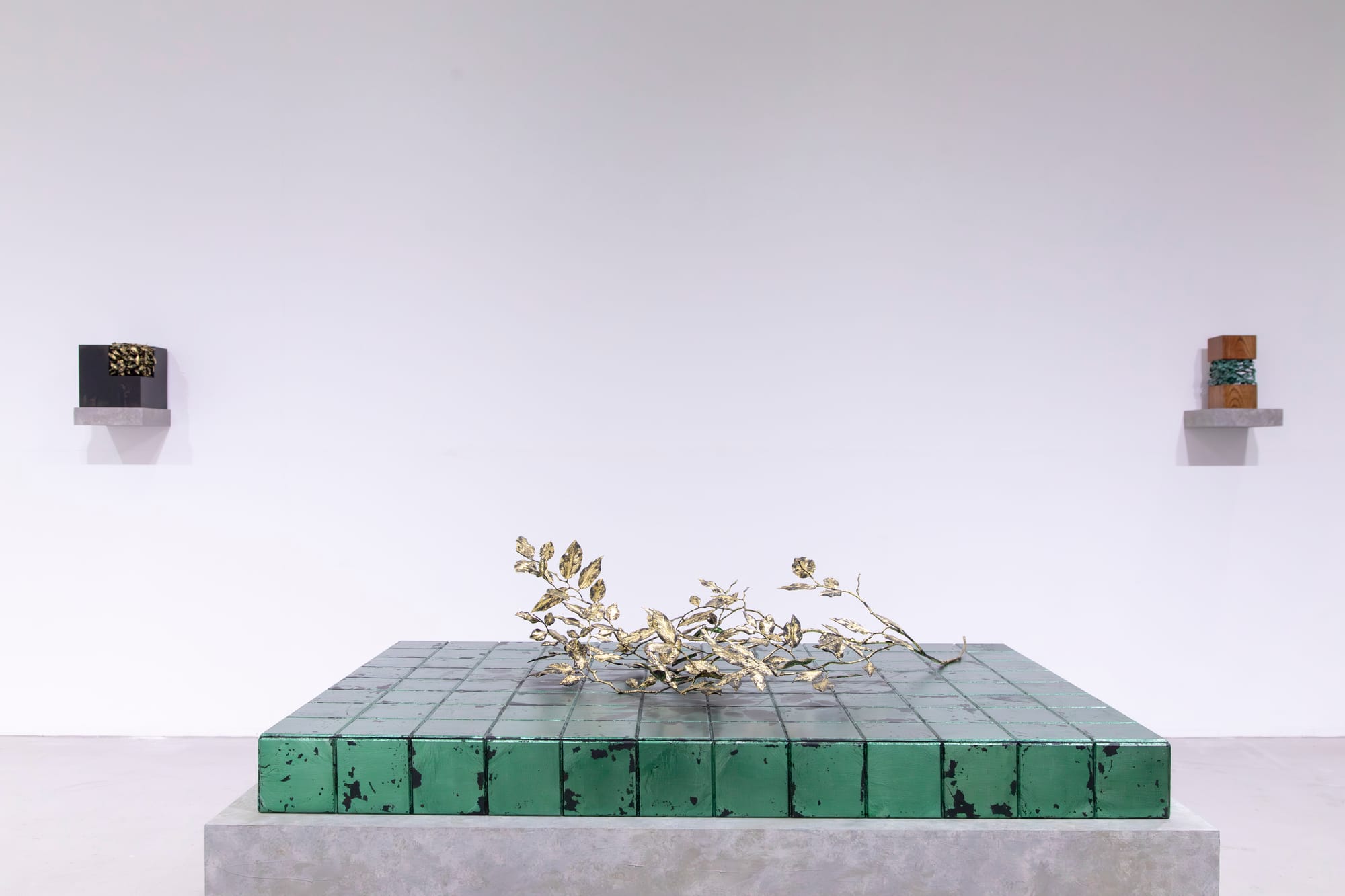

Take Ninagawa presented “Shinro Ohtake: Retina,” a collection of resin-covered chromogenic prints derived from decades-old degraded Polaroid negatives. The resulting images evoke extraterrestrial terrains or the colors and patterns of the human retina. At Kana Kawanishi Gallery, Kanji Hasegawa, a Tokyo University of the Arts sculpture graduate and former Soto Zen monk, experimented with ultraviolet (UV) prints in “Two Temporalities.” These prints served as trompe-l’oeil of actual shadows cast by intricately carved wooden wilting foliage against jewel-toned tiled backdrops. Hasegawa’s work explored the Buddhist concept of time as the duration between two events, contrasting with the Western linear, chronological perception. This contemplation was evident in the laborious process of carving and fixing the shadows using cyanotype printing, creating a contemporaneous record of the artwork’s creation.

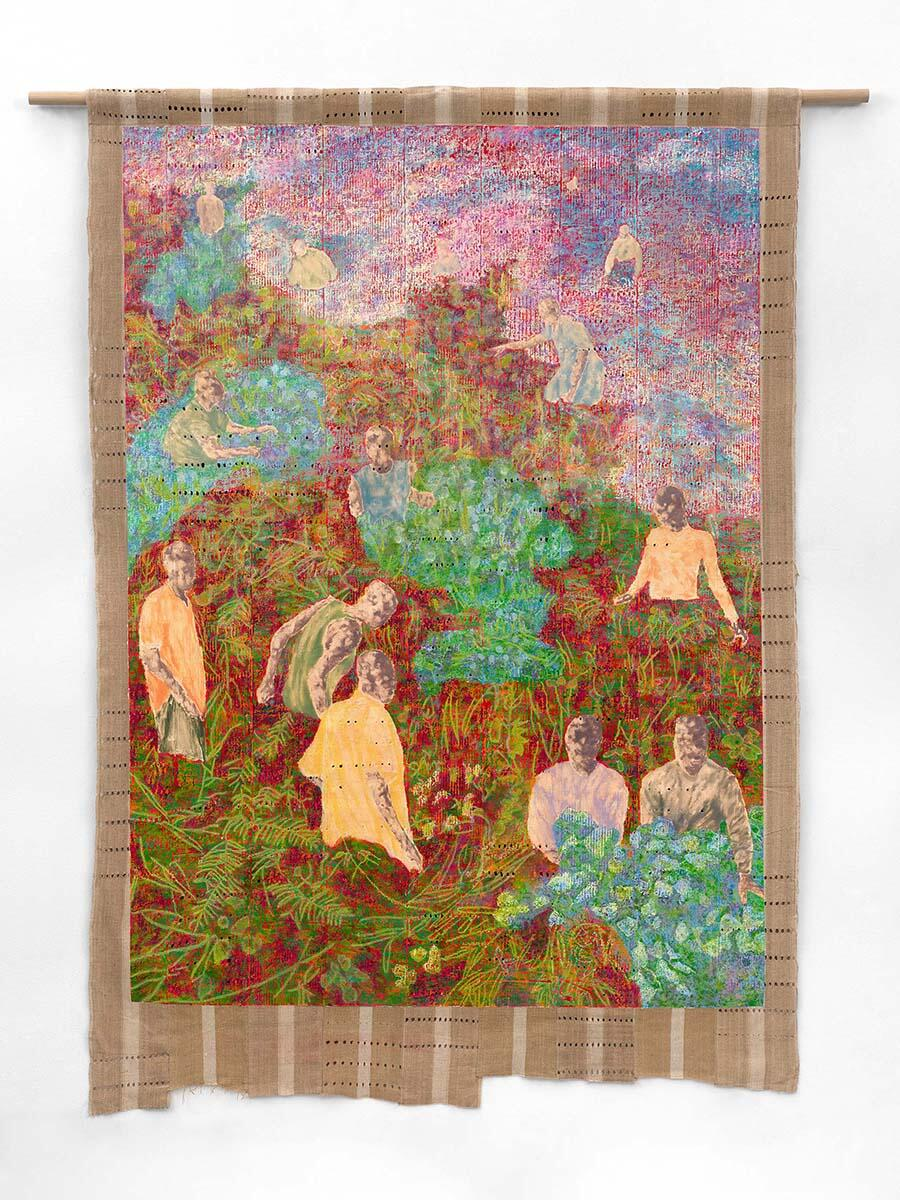

ṢỌLÁ OLÚLÒDE, In the Secret Garden of Our Love, 2025, dye, indigo, batik, wax, ink, pastel, and charcoal on canvas. Copyright the artist (left); and NENGI OMUKU, Along Fern River, 2025, oil painting on sanyan textile (right). Courtesy space Un Tokyo.

Ekow Eshun curated “The Clearing,” a group exhibition at the tucked-away space Un Tokyo, featuring works by African diasporic artists. The title, referencing Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), evoked a sanctuary for enslaved and freed townsfolk, with works by Okiki Akinfe, Kwesi Botchway, Ṣọlá Olúlòde, Nengi Omuku, and Arthur Timothy exploring kinship, love, and collective memory. The most arresting pieces were Ṣọlá Olúlòde’s In the Secret Garden of Our Love (2025), a portrait of two women kissing in a darkened forest inspired by her Caribbean travels; and Nengi Omuku’s Along Fern River (2025), an oil painting on Nigerian sanyan textile depicting community in nature. The curatorial positioning of space Un Tokyo may be strategic, given the growing interest in African diasporic artists in Asia. Arthur Timothy, for instance, exhibited a portrait at Art Basel Hong Kong earlier this year, and his works A Gathering Storm and Figures in a Landscape (both 2022) were included in Eshun’s exhibition.

Shunsuke Imai’s exhibition, “Singular Pluralities,” at Hagiwara Projects, featured colorful canvases reminiscent of 1990s CRT television SMPTE color bars. Inspired by the American Color Field movement and abstraction, Imai imbues his static, two-dimensional works with an illusion of movement, akin to a flag in the wind, through freehand swirls of geometric patterns and lines on carefully cropped canvases. He extended this exploration in his sculptural work, Untitled (2025), where a large patterned polyester cloth drapes over a stand. A canvas by Imai is also featured in Szymczyk’s “What Is Real?” at the Okura Museum of Art. Imai describes his vivid paintings as voids, reflecting his perception of Tokyo’s neon lights and fashion shops as being drenched in an overload of “chemical colors.”

Art Week Tokyo offered a rich experience, showcasing the city at its autumnal best. Beyond the vibrant gingko trees lining the streets, the city’s galleries and institutions provide a compelling cultural landscape. For those seeking mindfulness, quietude, and a genuine appreciation of art, Tokyo is unequivocally the destination.

Ryan Su is a Singapore-based contributing editor for ArtAsiaPacific, focusing on art and law. He is a practicing lawyer, and an accredited mediator and arbitrator.