Market

“The Edge is Fertile”: Asia NOW Rethinks Asia’s Borders

If there’s one certainty in the art world, it’s that its borders are fluid and forever shifting. Anyone who has spent time around fairs and biennales in the past three years has witnessed this, and the Parisian art fair Asia NOW reconfirms it with a new focus on what it calls “West Asia.”

A significant event of Paris Art Week, Asia NOW was founded in 2015 by Alexandra Fain and has since become Europe’s most relevant fair devoted to Asian art. This year, the decade-old salon, held in the historic Monnaie de Paris (Paris Mint), welcomes the emergence of art scenes from the Gulf. “We think of Asia as geography, but it’s also a methodology, a movement,” says Fain. “That’s why I’m bringing West Asia into the conversation, as a true conceptual reframe.”

This year’s program, centered on the idea of growth, frames art as a ground for transformation and collective flourishing. Arnaud Morand, one of the architects behind the fair’s non-commercial platform of commissions, talks, and installations, many of which focus on West Asia, produced four major commissions, organized a series of talks, and articulated a curatorial framework he calls “The Edge Is Fertile.” He explains: “For me, including the Middle East as a new geography and philosophy is about engaging with edges—namely, the spaces that are not usually taken into account when we think of Asia,” he explains. “I view Asia as an ecology of relations rather than a rigid continental line.”

There is, admittedly, a noticeable disconnect between the fair’s gallery section and its curatorial program: while most of the exhibiting galleries come from Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia, the intellectual and performative core of the fair leans decisively toward West Asia and the Middle East. Nevertheless, the coexistence of these diverse artistic geographies reinforces the fair’s central premise: that Asia today is a constellation of shifting relations in the process of being redefined by various forces.

Morand’s curatorial projects draw from Leela Gandhi’s idea of affective communities, which sees friendship as a radical, anti-imperialist force, and from Ibn Khaldun’s notion of al-ʿasabiyya, or collective cohesion, that allows cultures to thrive. The commissioned works respond to these ideas. For instance, Han Mengyun’s Under the Aegis of the Moon (2025), developed after a residency in AlUla, combines textile, video, and nocturnal performance to evoke the kind of attentiveness unique to the night—a sensibility attuned to landscape, silence, and geological time.

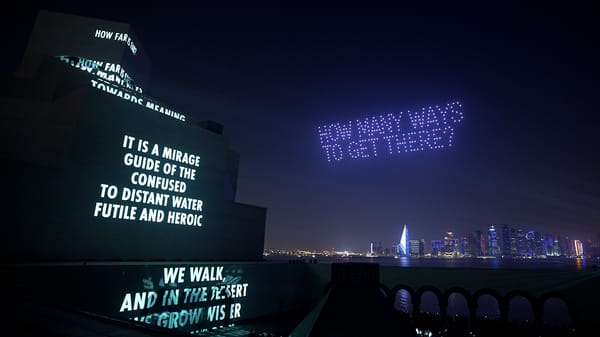

An intimate, corporeal thread runs through Morand’s selections: video diptychs of levitating bodies, performed poetry, and oral traditions. This focus contrasts with the typical impression of Gulf cultural programming, which often emphasizes monumental landscapes or large-scale, institution-backed spectacles (think light art festivals like Manar Abu Dhabi or Noor Riyadh). Morand instead foregrounds “artists who are more conceptual, less direct, working with the body, working with metaphysical themes.”

Having developed numerous artistic projects in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, Morand is candid about the political stakes involved. He recognizes the scale of cultural diplomacy at play: “It’s the result of an effective—at times aggressive—cultural policy aiming to normalize and globalize the Middle East as a new art platform and ecosystem,” he explains. “Gulf nation-states have invested massively in institutions, markets, and biennials. The next step is to be present on global platforms, so that local scenes don’t remain regionalized.”

The debate over whether to call the region the “Middle East” or “West Asia” signals a deeper conceptual shift. “Whether we call it the Near East, the Middle East, or West Asia depends on the paradigm we adopt,” says Morand. “What matters is the willingness to think of Asia as mutable and plural, rather than a monolithic identity that no longer makes sense.”

What clearly emerges from the fair is how the economic dynamism of the Middle East is fostering new connections between the Gulf and other thriving art scenes, from Korea to Southeast Asia. The expanding network raises the provocative question of whether Asia might soon bypass the West altogether, no longer seeking its stamp of approval. It’s a somewhat paradoxical question to ask in Paris, a city that remains a crucial hub for both the global art market and institutional credibility.

“Despite my reservations about the future of the West, I’m happy to bring Middle Eastern narratives to Paris,” reflects Morand, half-leaning against a mud architecture pigeon tower, a work by Saudi artist Ahaad Alamoudi, soon to be activated by a performance. Titled Ghosts of Today and Tomorrow (2022/25), the piece channels ancestral voices and revives old traditions as they germinate in the present, across different times and latitudes. The work poignantly captures the spirit of this edition of Asia NOW. “The Western world might be exploding, but here in Paris, I still see a strong effort to embrace a truly global artistic dialogue,” concludes Morand.

Naima Morelli is an arts writer and journalist specialized in contemporary art from the Asia Pacific and the MENA region.