Market

Space as Strategy: West Bund Art & Design 2025

What a difference a new venue can make, even in an uncertain market. Returning to Shanghai’s West Bund in November brought a curious mix of familiarity and disorientation. Familiar, of course, was the Huangpu River. But the empty sites that had been under construction last year were now filled—more shopping malls, office towers, and other commercial developments steadily claiming the waterfront. On November 13, the 12th edition of West Bund Art & Design officially opened, bringing together nearly 200 galleries and institutions, featuring works by over 1,000 artists from 65 countries and regions. This year, the headline was that the fair’s main “Galleries” sector had moved into the brand-new West Bund International Convention and Exhibition Center.

In previous years, the West Bund fair had occupied the West Bund Art Center, whose raw, industrial character gave the fair a certain grittiness. The new Convention and Exhibition Center, however, is purpose-built and professionally designed—the kind of infrastructure one would expect at Art Basel or other major art fairs. The reconfigured layout changed how collectors and visitors moved through the fair and how booths related to each other spatially. Speaking with several participating galleries, the responses were surprisingly consistent: the space felt larger, more open, and up to international standards. At a time when the market feels precarious—with galleries and fairs closing—West Bund’s investment in new infrastructure feels like a bet on the future, or at least a confidence boost.

Beyond the longstanding rivalry with ART021, another major art fair in Shanghai, West Bund also overlapped with Art Collaboration Kyoto (November 13–16). Many believed this scheduling diluted the attention of international collectors and exhibitors, most visibly reflected in the absence of West Bund regulars like blue-chip galleries Gagosian and Pace. Still, this year, both fairs in Shanghai benefited from coinciding with the 15th Shanghai Biennale, creating the kind of institutional-commercial overlap that draws curators, collectors, and visitors to the city during the same week. The fair’s reorganization strategy was straightforward: redistribute the venue, optimize the traffic flow. Moving the main “Galleries” sector into the new convention center freed up the old West Bund Art Center for its “Xianchang” sector, which highlights large-scale installations and thematic projects.

The result was immediately visible in what galleries brought. Compared to ART021—which still focuses heavily on paintings and smaller sculptural works—West Bund hosted considerably more ambitious three-dimensional pieces. For example, White Cube presented a galvanized steel sculpture, Zazen (1982–83), by Isamu Noguchi. Asia managing director Wendy Xu remarked that the new venue “brought a clear enhancement to the fair experience,” with “a more centralized layout that offered a sense of coherence and comfort that benefited both galleries and collectors alike.” Massimodecarlo showcased a towering red Yan Pei-Ming canvas depicting Bruce Lee, paired with one of Yeesookyung’s reconstituted ceramic vases.

Galleries that participated in both fairs exhibited noticeably larger sculptures or installations at West Bund, or opted for more thoughtful curations. Ota Fine Arts, for example, brought a compact Yayoi Kusama presentation of small paintings and modest-sized sculptures to ART021, while at West Bund, they staged a group show that included a standalone structure built onto the booth’s exterior, dedicated entirely to Chen Wei’s photography and sculptural works. The walls and floor were clad in turquoise tiles that reflected light like ceramic glaze, creating an immersive environment.

Leading Chinese galleries likewise seized the opportunity to think outside the box. ShanghART installed Chen Xiaoyi’s two-meter-tall UV-printed aluminum sculpture Those Meander Worries in Barren Shell #1 (2021) alongside Zhang Ding’s High-speed Forms #4 (2019), which features a car seat mounted on a steel pillar. Beijing Commune gave prime real estate to Liu Jianhua’s Temperature No. 10 (2025), a sprawling ceramic form resembling calcified branches or roots. Hua International, a gallery based in Beijing and Berlin, built one of the fair’s most interesting booths, in which Chen Jinbin’s figurative paintings hung from suspended metal panels, while clothing racks nearby displayed shirts created by artist collective CFGNY—readymades presented as wearable sculpture, art displayed like retail.

Hong Kong galleries staged some intriguing presentations too. De Sarthe constructed a small room within their booth, its walls and ceiling wrapped in crinkled reflective fabric that shimmered like foil, inside which Lov-Lov’s video There are No Safe Games (2024) played on loop. Blindspot Gallery gave Chinese artist Zhang Wenzhi an entire solo booth featuring paintings, screens, scrolls, and sculptures. Axel Vervoordt, the Belgian gallery with a Hong Kong outpost, showed Kimsooja’s Bottari (2025), a fabric work made from textiles and secondhand clothing the artist collected in Hangzhou. The piece generated a quiet energy that was allowed to breathe and expand in the spacious environment of the fair’s new venue.

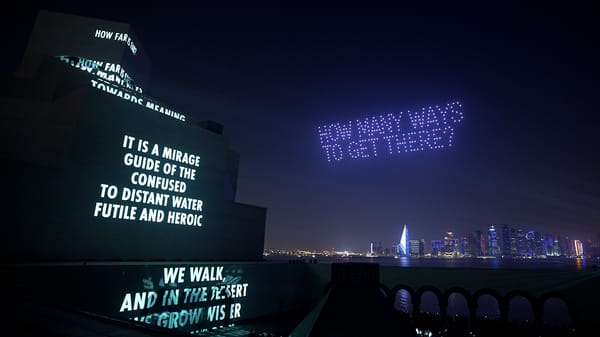

Meanwhile, the old West Bund Art Center was repurposed for “Xianchang,” a sector dedicated to large-scale installations and ambitious curatorial projects. Walking in, the first thing one noticed was ShanghART’s presentation of artist Hu Xiangcheng. The project consumed nearly a third of an entire floor, featuring paintings, sculptures, shipping containers, metal scaffolding, boom lifts, and more. The scale was industrial, almost architectural, utilizing the raw space in ways conventional booths would not accommodate.

“Xianchang” also hosted Paula Cooper Gallery’s archival presentation. The New York institution, approaching its 60th anniversary, brought rare photographs, documents, and ephemera tracing the gallery’s history and its connection with major movements of the 1960s and ’70s. Nearby, Vietnam Art Collection (VAC) presented the group show “Murmurs: A Gathering of Modern and Contemporary Arts from Vietnam”. The booth was modest in size but expansive in scope, tracking multiple generations and geographies, from older artists who left Vietnam for France decades ago to younger practitioners who combine traditional forms with contemporary concerns. Some worked from within Vietnam; others from diasporic positions in Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia. The presentation made a case for Vietnamese contemporary art as neither monolithic nor marginal, but rather a tradition with depth, complexity, and vitality.

This year’s edition of West Bund demonstrated a kind of ambition: it maintained the fair’s commercial core while creating room for works and presentations that don’t fit neatly into art fair booths. As Shanghai Art Week becomes more firmly embedded in the Asian-Pacific art calendar, can West Bund evolve into the kind of anchor fair that draws collectors not only from the region but also from Europe and North America? For now, the infrastructure is in place, and what gets built on top of it depends on decisions yet to be made.

Louis Lu is an associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.