Market

Slow and Purposeful: Art Basel Qatar 2026

“I hope that what people can take home is a sense of discovery. In the region, there is a great deal of exceptional art and institutions of the highest level that, due to a series of geopolitical circumstances, have not been as visible as they deserve to be. If we do a good job, we can help facilitate that visibility—which is what we strive to do across all our fairs around the globe.”

—Vincenzo De Bellis, Art Basel’s chief artistic officer and global director of art fairs

At the beginning of February, the art world descended on Doha, Qatar, for the first edition of Art Basel Qatar (ABQ), which ran through February 7 in M7 and Doha Design District. Backed by a state-led cultural policy aimed at shifting the country’s financial model from an extractive economy toward culture and education, a process already underway elsewhere in the Gulf—notably in the UAE and more recently in Saudi Arabia—ABQ proposed a new model: slower, more purposeful, and constructed specifically for the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia (MENASA).

Welcoming 87 international exhibitors and 84 artists across two venues, considerably slim compared to the usual 100–300 participations at other major fairs, ABQ articulated itself through a thoughtfully curated solo-show model. This approach offered unprecedented visibility to many artists from the MENASA region. As articulated by Wael Shawky, artistic director of ABQ, to ArtAsiaPacific: “It was fundamental to make this first edition unique. Not only because we have only one artist per booth, but also unique in the sense that it needed to reflect the vision and understanding of this region, of place, but also of quality.”

The fair’s curatorial direction followed the concept of “Becoming,” an idea not only central to Shawky’s practice as an artist but also fundamental in reflecting the vision of Qatar and the Gulf region at large. Shawky explained in an interview with ArtAsiaPacific, “Becoming is part of an idea of a society that is developing from one system to another, a higher one. You can see the dream of developing extremely fast, and that is what is happening in Qatar.”

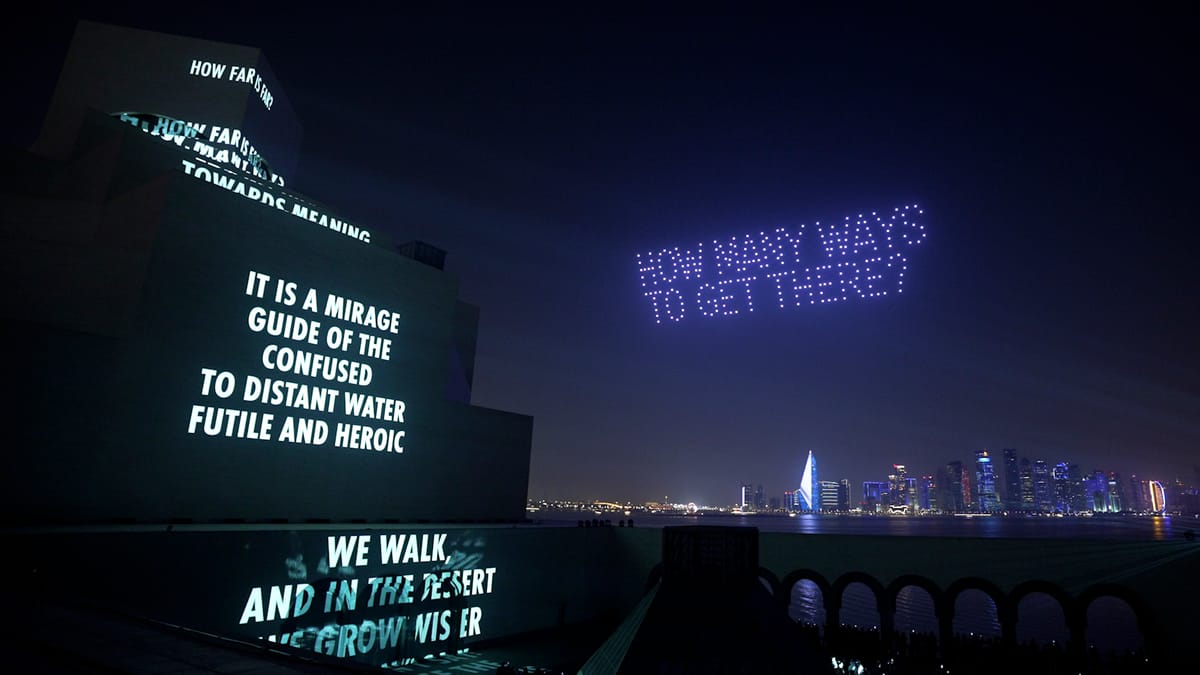

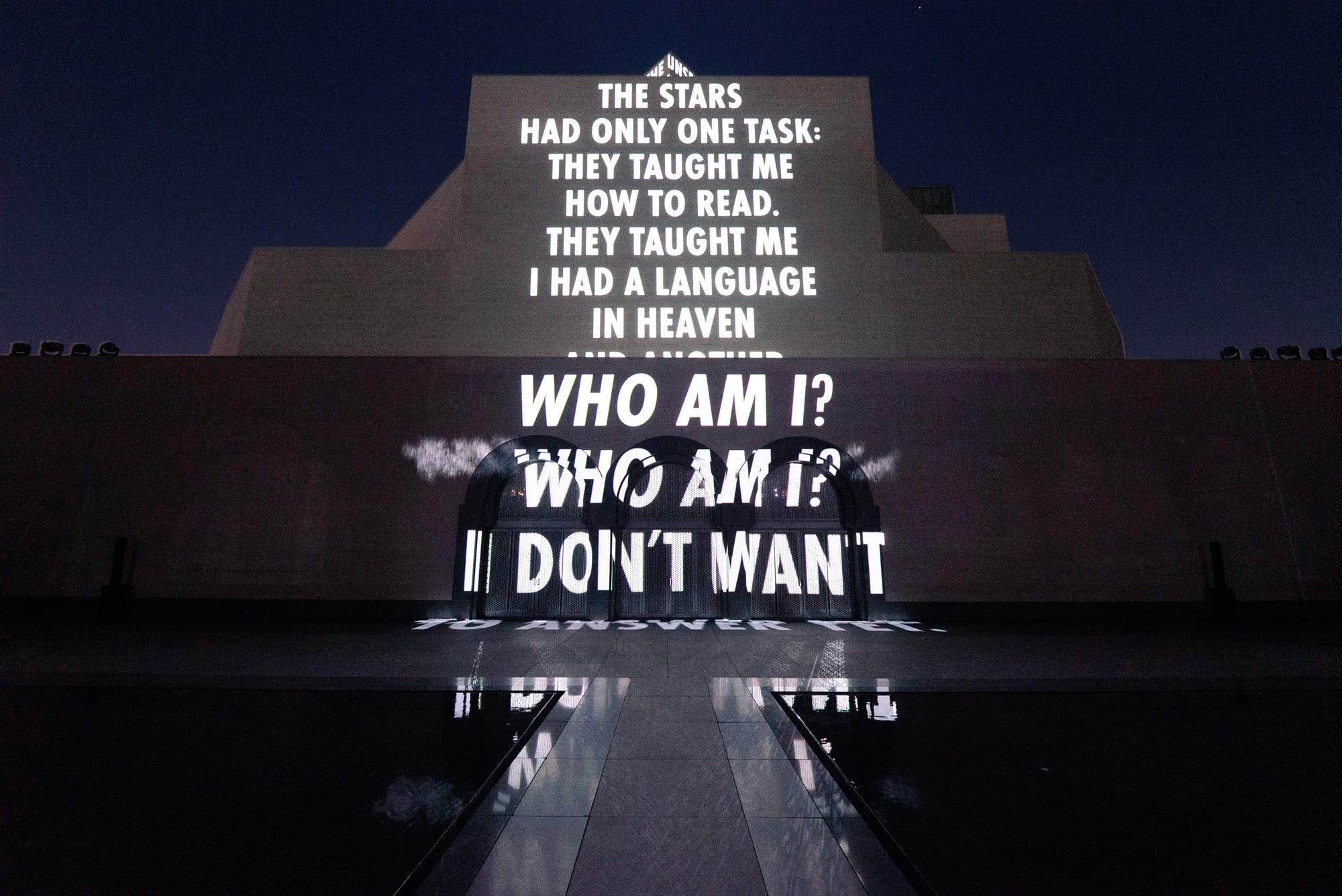

This sense of deep investment in art was palpable both inside and outside the fair venues. Art Basel developed a carefully structured program for international visitors to discover Doha’s cultural ecosystem and institutional landscape. The inaugural soirée was held at the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA), where a new light commission by Jenny Holzer was unveiled on the facade of I. M. Pei’s iconic building, accompanied by a large-scale drone performance in the adjacent sky. Titled SONG (2026), the projection paid homage to writings by the late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish and acclaimed Emirati poet Nujoom Alghanem, unfolding in both Arabic and English. The museum also hosted “Empire of Light: Vision and Voices of Afghanistan,” a major exhibition exploring 5,000 years of Afghan art and heritage, juxtaposing antiquities and historical artifacts with contemporary voices.

Another notable exhibition presented as part of the Art Basel program was “we refuse_d,” curated on the occasion of the 15th anniversary of the Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art. Referencing the historical Parisian Salon des Refusés, the exhibition presented works, many of them new commissions, by artists working under conditions of silencing, censorship, and displacement. Among them, the work of Palestinian American artist and scholar Samia Halaby resonated particularly strongly. Amid the intensifying conflict in Gaza, many of her recent exhibitions across the US had been canceled.

The broader geopolitical climate, especially the escalating Iran–US tensions, was not ignored within the fair’s context. Many collectors and dealers acknowledged a growing sense of economic uncertainty in the region. Nonetheless, most remained optimistic, emphasizing that they were playing a “long game” in Qatar. Several confirmed their intention to return in the coming years, citing particular interest in developing relationships with the Gulf’s growing museum sector. This condition, poised between instability and future-oriented ambition, was compellingly explored in the exhibition “What’s between, between?” on the idea of Gulf Futurism at the Media Majlis Museum at Northwestern University in Qatar, where contemporary artists from the region examined this liminal state through media and time-based works.

The overall quality of the fair was exceptionally high, offering both local and international audiences presentations that would be difficult to encounter elsewhere. Among them, Beirut-based Galerie Tanit presented the work of Helsinki-based Iraqi artist Adel Abidin, showcasing The Revolt, a multidisciplinary project initiated in 2023 that explores the Zanj Rebellion. Particularly striking was Documents on Salt (2024), a series of sculptures carved from natural salt sourced from the Dead Sea, functioning as a speculative “missing archive.” Other standout presentations by regional galleries included Tracing Lines of Growth (2024), a palm-leaf installation by Saudi artist Linza Gazzaz presented by Hafez Gallery; sculptures by Sudanese American artist Amir Nour at Lawrie Shabibi; Ahmed Mater’s Temporal Migration, a photographic project on Mecca and its layered histories at ATHR Gallery; Tabari Artspace’s presentation of Palestinian artist Hazem Harb, whose project mobilized archaeology as a critical framework to examine displacement, circulation, and epistemic violence. Notable also was Pakistani artist Rasheed Araeen’s work at London-based Grosvenor Gallery, especially the not-so-subtly ironic Jouissance (1993–94), which depicts a Western woman handing a pack of cigarettes bearing the word “West” to a muslim woman.

Equally striking was the juxtaposition, on the fair’s first floor, of blue-chip presentations of historical artists—such as Pablo Picasso at Van de Weghe, Jean-Michel Basquiat at Acquavella Galleries, Philip Guston at Hauser & Wirth, and Georg Baselitz at White Cube—alongside the work of Pakistani artist Rashid Rana, presented by Chemould Prescott Road. Titled Fractured Moment (2025), Rana’s installation features sequential CCTV stills of the Gaza conflict printed on wallpaper. It was priced at USD 30,000, with all the proceeds going to Gaza relief funds. Several international galleries also chose to engage more deeply with the region by spotlighting artists with strong cultural or geographic ties, including Thaddaeus Ropac’s presentation of London-based Kashmiri artist Raqib Shaw, Lia Rumma’s presentation of a new video work by Shirin Neshat, Almine Rech’s presentation of Lebanese artist Ali Cherri (whose work is already widely collected in Qatari Museums), and Galerie Lelong and Ames Yavuz’s presentation of Thai artist Pinaree Sanpitak.

Beyond the fair’s walls, overseas guests had the opportunity to venture into the desert to experience major permanent installations by Richard Serra and Olafur Eliasson. Another notable project—more difficult to locate, as only GPS coordinates were provided, intentionally making the journey part of the experience—was Rahaal, a nomadic museum unfolding across three pavilions (an exhibition space, a salon, and a library) in the historic nature reserve of Zekreet. Co-organized by Mohammed Rashid Al-Thani, founding director and curator of the Institute of Arab and Islamic Art, and designer William Cooper, the project drew inspiration from the tradition of Arab hospitality and the heritage of the majlis. It invited visitors into shared conversations alongside a selection of paintings on loan from various galleries and institutions, all addressing the connection between humanity and nature through the traveler lens, hinting at traditional nomadic culture and the relationship between Qatar and the desert. The exhibition was aptly titled “Anywhere Is My Land.”

These experiences of conversation and discovery echoed the words of Vincenzo de Bellis, Art Basel’s chief artistic officer, who remarked in a conversation with ArtAsiaPacific: “The goal was to create something centered on the culture and the way of being and living in the region, a different kind of fair, one that allows for much stronger inside/outside connections. Time for all of us to reflect, to look, and to think about things, while still acknowledging that this is a commercial project, which is what we are.”

As the first edition came to a close, ABQ dabbled with a markedly different model—one that, amid frenetic calendars, market-driven pressures, and global uncertainty, invited a deeper reconnection with art. Enabled by a unique relationship between the fair and the Qatari state, and by a sustained investment in culture, this model is not easily replicable elsewhere. Yet it opens space to imagine alternatives. Time will tell whether, beyond this inaugural experiment, such an approach can develop into a sustainable, long-term economic model—not only for Art Basel and its host cities, but also for galleries themselves.

Valentina Buzzi is a curator, writer, and PhD candidate based between Paris and Seoul. Her cross-cultural, interdisciplinary research focuses on modern and contemporary Korean art, particularly its local contexts and international circulation.