Market

Home Ground: Tokyo Gendai 2025 and the New Asian Circuit

September in Japan is often called geijutsu no aki (芸術の秋)—the autumn of art. Tokyo Gendai’s third edition, running September 11–14 at Pacifico Yokohama, moved from its previous July slot to capitalize on this cultural moment, directly following Frieze Seoul and aligning with Japan’s major cultural activities, including Expo 2025 Osaka, Tennoz Art Week 2025, and the recently opened Aichi Triennale. The fair also launched an international curatorial forum and an Art Busan collaboration, signaling attempts to build stronger connections between Japan’s art market network and the broader East Asian art ecosystem.

According to the 2025 Art Basel & UBS report, global art sales fell 12 percent last year while Japan saw a 2-percent increase, with the gallery sector contributing 7 percent of that growth. Meanwhile, China's market dropped 31 percent and South Korea’s dropped 15 percent. Despite China maintaining the largest market share in Asia, Japan’s position as Asia’s second-largest art market appears increasingly stable. Within this context, this year’s edition of Tokyo Gendai brought together 66 galleries across three sectors: the main Galleries sector, Hana (“Flower”) for emerging and mid-career artists, and Eda (“Branch”), which focused on established and historically significant Asian figures.

Among returning international galleries, Sadie Coles HQ featured a large blue figurative painting by Yu Nishimura that drew considerable attention. A rising Japanese star who recently joined mega-gallery David Zwirner, Nishimura is known for his dreamlike, semi-blurred portraits and cityscapes, composed of simplified shapes, which carry a melancholic nostalgia. Pace, which showed a solo presentation of American artist Robert Longo last year, opted for a diverse international group show including playful and surreal sculptures by artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset, Ghanaian artist Gideon Appah’s jewel-toned figurative paintings, and French artist Jules de Balincourt’s vibrant paintings that explore sociopolitical dynamics in a globalized world. Having opened their Tokyo space last year, Pace showed a long-term commitment to the Japanese market not only through maintaining a physical presence but also through a clear effort to introduce their broader international roster to local collectors, testing which artists and styles resonate with Japanese tastes.

The Japanese galleries are still the backbone. According to the Japanese Art Market report published last December, Japan has a network of over 2,060 art businesses, with 59 percent operating in Tokyo and 66 percent in the broader Kanto region. For those wanting to understand Tokyo’s art scene, Tokyo Gendai provides an efficient overview of the city’s gallery landscape. Taka Ishii Gallery, established in 1994 and one of Japan’s leading galleries, presented paintings by different generations of domestic and international artists. Beyond showing new works by well-known names such as Erwin Bohatsch, Oscar Murillo, and Tomoo Gokita, they actively promoted young local artists born after 1995—for example, Fu Nagasawa, Takuma Oue, Reika Takebayashi, and Kohei Yamada. The booth featured primarily abstract paintings with rich colors and layered complexity.

Another Japanese gallery, Takuro Someya Contemporary Art debuted an abstract painting by Kenjiro Okazaki, whose large survey ran from April to July at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. The new work, composed of two differently-sized canvases covered with varied abstract brushstrokes, continues the artist’s investigation of materiality, form, and tactility. At ShugoArts, among its group display was Ikemura's iconic hybrid-figurative sculptures rendered in translucent yellow glass and a fiery red expressionistic apartment-friendly canvas. Like Okazaki, Ikemura is among the leading Japanese artists represented by both Japanese and international blue-chip galleries.

Taro Nasu Gallery, established in 1998 and known for promoting conceptual art, represents international artists like Pierre Huyghe and Lawrence Weiner while actively supporting midcareer and young local artists. They brought works by Ryoji Ikeda, Simon Fujiwara, and Mika Tajima. In a corner booth, young gallery Parcel, which focuses on experimental local and international artists, featured a solo presentation by Masamitsu Shigeta. Based between Tokyo and New Jersey, the artist captures random fragments of urban daily life through paintings and customized frames, exploring the dynamic relationship between 2D and 3D, psyche and landscape.

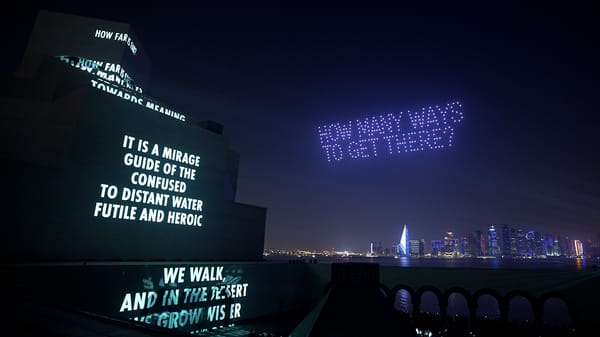

The fair’s new September schedule, which opened immediately after Frieze Seoul, has allowed international visitors and collectors convenient access to both cities. Additionally, the new Art Busan partnership brought nine Korean and two Chinese galleries to this year’s edition. Johyun Gallery, established in Busan in 1989, presented Asian art historical masters associated with Korean Dansaekhwa and Japanese Mono-ha, including works from Park Seo-Bo’s Ecriture series, a small wooden installation by Mono-ha master Kishio Suga, and a charcoal sculpture by Korean artist Lee Bae. Beyond the main galleries sector, Johyun Gallery also participated in the Sato (“Meadow”) program, a curated section for large-scale installations and performances, where they presented a solo project by Kim Taek Sang. Regarded as an artist of the second generation of Dansaekhwa, Kim explores water’s fluid properties through repeated settling of diluted pigments on canvases.

ShanghART and BANK were the only two galleries from China. ShanghART brought different generations of Chinese artists. At the booth entrance was a large mixed-media abstract painting by artist Hu Xiangcheng, who lived and studied in Japan during the 1980s. In this work, Hu repeatedly built up and deconstructed the canvas with thick pigments, exploring the relationships between material, time, and traces. “We came without major expectations. It’s more about ‘stepping out,’” ShanghART owner Lorenz Helbling told me. Given China’s uncertain economic climate, rather than holding ground, stepping out could be an active strategy. And Shanghai-based BANK seems to share this outward approach, making their Tokyo Gendai debut while also testing waters in New York with a pilot space that opened earlier this year. For the fair, BANK brought artists familiar to Japanese collectors, including a video work by Japan-resident Lu Yang and paintings by Tokyo-born Taiwanese artist Michael Lin, which are inspired by traditional cherry blossom textile patterns. Both galleries gave East Asian artists visibility in Japan.

Like its previous editions, this year’s visitors and collectors came primarily from Japan, with international—and mostly newer-generation—collectors joining the expanded VIP program from South Korea and nearby countries. Ahead of the fair’s opening day, I visited young collector Yu Kimoto’s art space. His Aoyama studio houses numerous Isamu Noguchi lamps and pieces by renowned 20th-century furniture designers, alongside street artist KAWS’s collage works and conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner’s wall text pieces. Kimoto represents a common trajectory among a fresh-crop of Japanese collectors who, like those in other major Asian art capitals, often transition from collecting sneakers and designer toys to furniture and contemporary art.

In the current global art market, Japanese postwar and contemporary art are still dominated by familiar names: Gutai masters, contemporary stars such as Kusama, Nara, and Murakami, and blue-chip artists like Izumi Kato and Leiko Ikemura. The majority of gallery sales were made to buyers at home and neighboring countries. While established Japanese stars gain global reach through mega galleries, the nation’s younger artists—typically represented by homegrown galleries—lack comparable connections to gain broader international visibility. Tokyo Gendai seems to recognize this challenge and, rather than attempting to rival Art Basel Hong Kong or Frieze Seoul directly, it might find its strength in maintaining a local character while building networks across East Asia.

Louis Lu is an associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.