Market

Breaking New Ground: Interview with Pascal de Sarthe

Founded in the late 1970s by Pascal de Sarthe, De Sarthe Gallery is a distinguished pillar of the art scene in Asia, its legacy embodying a steadfast commitment to artistic integrity and community building in an ever-evolving art world. Embracing tradition and innovation, the gallery charted a remarkable journey spanning continents, from its early days brokering Impressionist and Modern works in San Francisco to its current dynamic presence in Hong Kong’s contemporary art scene. On the eve of De Sarthe’s expansion to a brand new space in Wong Chuk Hang, Elaine W. Ng spoke with Pascal about his personal journey and visionary approach.

Elaine: Can you share a specific moment—such as an encounter with a work of art or an individual—that first made you realize you wanted to dedicate your life to art and living artists?

Pascal: My passion for art began early. I started drawing and painting at 11, and by 18, I was creating conceptual and performance works, even participating in group shows at museums—one in Germany and two in France—and exhibiting in galleries. A pivotal moment came in 1977, when a friend offered me an empty space to use as a gallery. I transformed it into a platform for my work and that of fellow artists. Later, another friend invited me to run his newly opened space, where I organized monthly contemporary shows and even held a solo exhibition of my own. Those two years planted the “gallery bug” in me. Then, at 22, I woke up one morning and told my wife, “I’m no longer an artist, I’m going to focus entirely on the gallery.”

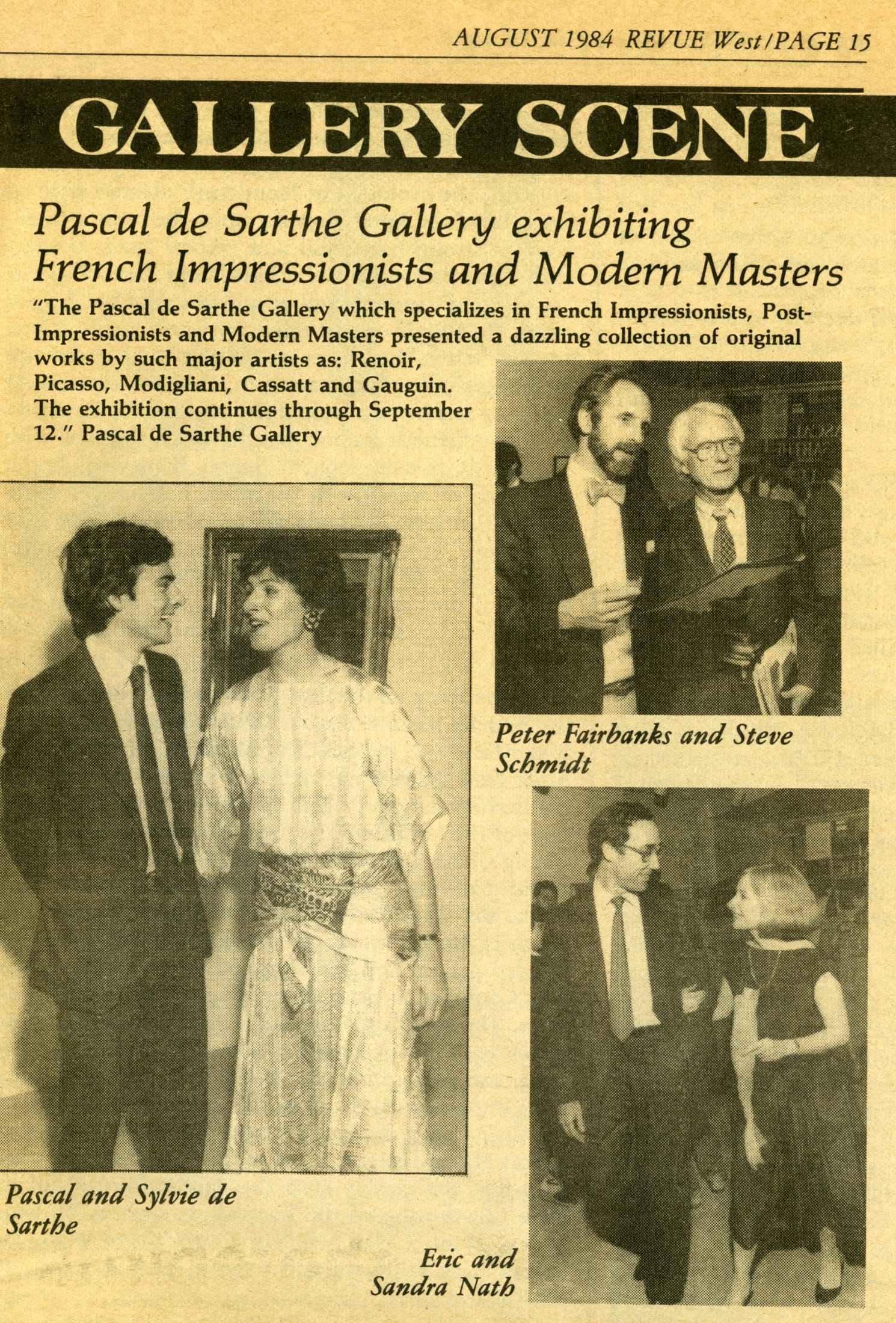

Left: PASCAL DE SARTHE and SYLVIE DE SARTHE in Revue West, 1984. Courtesy De Sarthe, Hong Kong. Right: Exterior view of Pascal de Sarthe Gallery in San Francisco, 1981–90. Courtesy De Sarthe, Hong Kong.

I began brokering secondary market works, primarily Impressionist and Modern, before moving to San Francisco a year later. When I arrived in the US with my wife and our one-month-old daughter, we had a one-way plane ticket, one night booked at a hotel, and just enough money to cover a month’s rent. I didn’t yet speak English. Needless to say, it was a bold, if not slightly crazy, leap of faith! Yet within six months, I opened a gallery. Every day was a gamble. Dealer friends from France sent inventory, and collectors loaned works. Through lots of luck and determination, I gradually built a collector base. The gallery’s location in San Francisco—a hub for tourists and conventions—was key to its success. I started with Impressionist works and later expanded into postwar and contemporary art.

At the time, the gallery model was straightforward: You were either a broker or a gallerist. Collectors rarely resold works, unlike today. My focus was simple: to combine both roles—presenting the best art I could find, connecting it with buyers worldwide, and treating the gallery not as a shop, but as a space for dialogue. Less than a year after opening, I expanded my business through regular travels to Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, and Singapore, steadily developing an increasingly international presence.

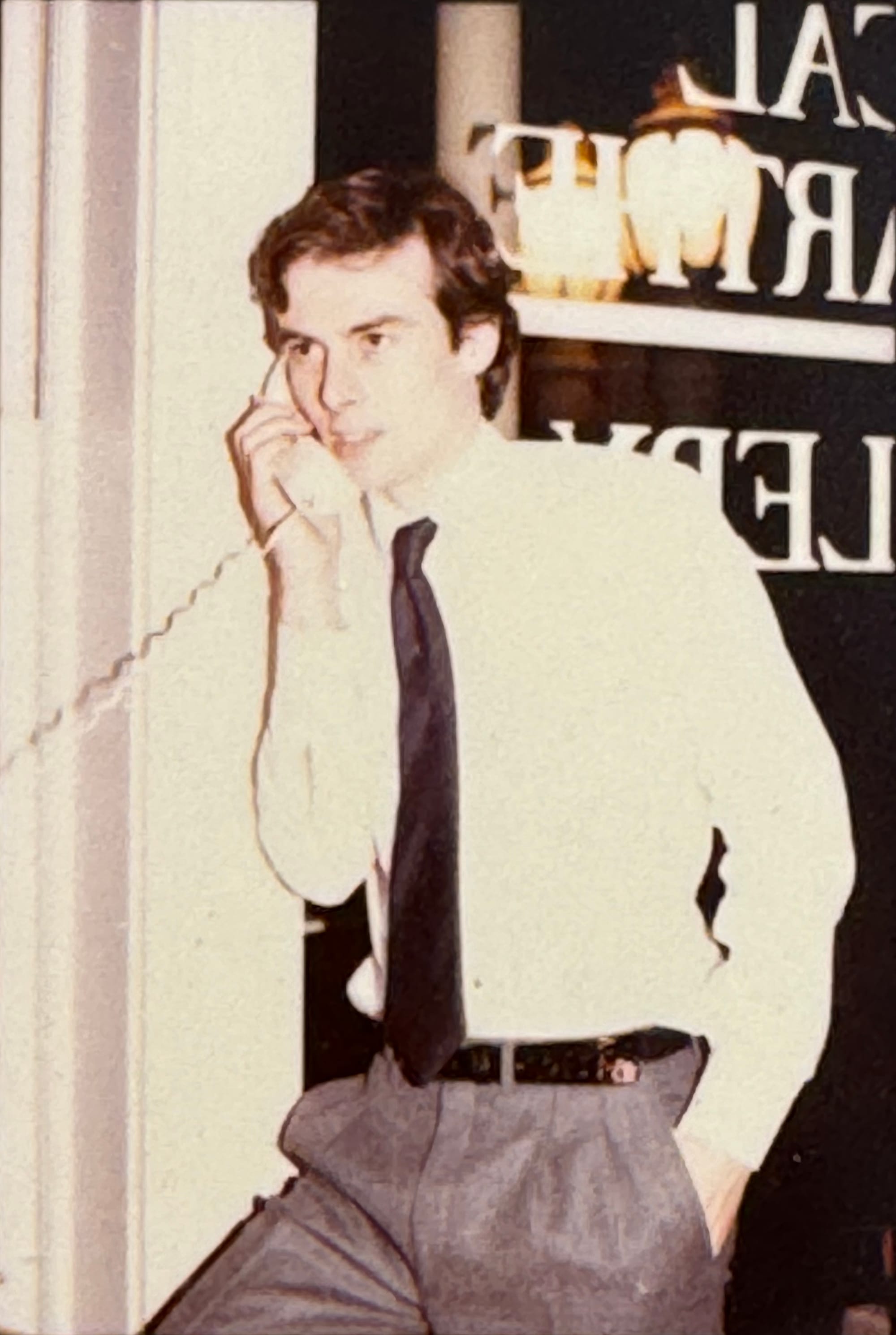

Left: PASCAL DE SARTHE in San Francisco, 1982. Courtesy De Sarthe, Hong Kong. Right: Installation view of “Colorfield Artists” at Pascal de Sarthe Gallery, Los Angeles, 1993, featuring works by KENNETH NOLAND, HELEN FRANKENTHALER, JULES OLITSKI, and MORRIS LEWIS. Courtesy De Sarthe, Hong Kong.

Elaine: Your career has spanned many locations around the world: Paris, San Francisco, Beijing, Scottsdale, and Hong Kong. How has each city shaped your view of what a gallery should be?

Pascal: Initially, I didn’t think location had an influence on my vision. I was more focused on sourcing great art than engaging with local communities. That changed in 2010 when I moved to Asia. After two decades of frequent trips to Asia and growing connections, I settled in Hong Kong and opened a space. Visiting artists’ studios across China, I encountered artists such as Lin Jingjing, whose work captured the country’s rapid transformation and the impact of new technology on human behavior. Fascinated by the work, I began repositioning the gallery as a platform for these conversations, shifting from a transactional model toward one grounded in artistic engagement. This, to me, is the essence of contemporary art.

Elaine: When you moved to Hong Kong, your first setup was in Central. How would you describe the character and the idea of community in Wong Chuk Hang compared to your experience in Central—or other cities you have operated in? Moving De Sarthe Gallery to a 929-square-meter space in Wong Chuk Hang feels more than a logistical, commercial decision—it’s a statement. What will be different aside from sheer scale?

Pascal: Wong Chuk Hang offers galleries a fundamentally different context from Central—one defined not only by scale, but by potential. In Central, high rents and commercial pressures often force galleries to adopt a retail model, where art risks being reduced to a luxury commodity rather than a medium for dialogue. Wong Chuk Hang, by contrast, provides the physical space to prioritize artistic community and experimentation. Its industrial architecture, lower costs, and growing concentration of galleries foster an ecosystem where emerging artists and younger galleries can thrive. Here, art isn’t just displayed—it’s given room to breathe, to provoke, and to engage with audiences on a deeper level. The district’s transformation mirrors a broader pattern seen in cities like New York, where neighborhoods became art hubs. Yet Wong Chuk Hang’s evolution is distinctly Hong Kong—rapid, adaptable, and marked by a mix of industrial grit and creative energy. This isn’t just a relocation; it’s a recalibration of what an art district can be.

Left: Installation view of “Zao Wou-ki Paintings 1950’s-1960’s” at De Sarthe, Hong Kong, 2011. Courtesy De Sarthe. Right: Installation view of "Rodin: Bronzes, Exceptional Early Casts" at De Sarthe, Hong Kong, 2013. Courtesy De Sarthe.

When I first arrived in Hong Kong, Central seemed like the obvious choice, but its business-centric environment and prohibitive rents quickly revealed the limitations. Galleries there either catered to high-end retail or struggled to sustain a program that balanced commercial viability with artistic integrity. When Fabio Rossi introduced me to Wong Chuk Hang in 2017, I immediately recognized its potential. With a handful of serious galleries already in place, the area had the raw energy of a nascent art community—reminiscent of early-days Chelsea in New York. The move was transformative. For the same cost as my 279-square-meter space in Central, I opened a 929-square-meter gallery, a shift that fundamentally changed how I could work with artists. The space wasn’t just larger; it symbolized a commitment to sparking exchange between established and emerging practices.

After losing that lease post-COVID, I temporarily scaled down operations. Now, with this new 929-square-meter location, my original vision can be fully realized again: one space dedicated to historically significant 20th-century works, and another serving as a platform for the next generation. Wong Chuk Hang’s community is unlike Central’s—it’s collaborative, not competitive. The artists, gallerists, and collectors here are invested in building something collectively, not just transacting. This spirit influences the exhibitions I envision: more ambitious, more experimental, and more connected to the key discussions in contemporary art globally. Hong Kong’s art scene is now dynamic; in Wong Chuk Hang, it is developing a distinct voice rooted in the art community.

Elaine: Your gallery uniquely spotlights emerging Chinese artists working with new technologies. What attracts you to this generation, and in what ways do they challenge your thinking as a gallerist?

Pascal: For decades, the art world has promoted collecting contemporary art as both a class asset and a ticket to elevated social status. While this idea became reality for a privileged few, for most participants it resembled a Ponzi scheme—leaving many now facing a harsh awakening.

Contemporary art should not be viewed primarily as a financial investment or a status symbol. Instead, it should be seen as a shared engagement in cultural dialogue. Over time, certain works may gain historical significance, increase in value, or even elevate an artist’s standing in the art world. But if that is the sole objective, the pursuit is likely doomed to fail. Much of what appears in contemporary galleries and museums today recycles 20th-century ideas, frequently drawing on the familiar references. Yet, as we enter the first quarter of the 21st century, a new generation of Chinese artists is breaking ground and forging a new cultural identity. Emerging technologies, AI, blockchain, quantum computing, and other unforeseen developments, are reshaping human behavior. These shifts provide fertile ground for artistic exploration, and engaging with artists who tackle these themes excites me. For now, this art conversation is the only purpose of maintaining a physical space. I believe technology will soon revolutionize not just how art is made, but how it is experienced.

Elaine: As a gallerist who is also internationally known for showcasing modern masters, how do you balance tradition and innovation in your current programming?

Pascal: Art history is essential. When engaging with modern masters, I draw upon their 20th-century legacies, while with contemporary artists, I seek out bold, unexplored narratives. Over the years, I’ve been fortunate to cultivate a contemporary program that is now starting to resonate deeply with leading collectors and institutions.

Elaine: In our fraught global sociopolitical moment, do you view your gallery as a purely aesthetic space, or is it also meant to be a site of social engagement?

Pascal: Art is shaped by the time it inhabits. Using new tools, technologies, and discourses available to artists in the present moment, I view my gallery purely as a platform for engaging with contemporary cultural exchange.

Left: PASCAL DE SARTHE and VINCENT DE SARTHE at Art Basel Hong Kong, 2015. Courtesy De Sarthe, Hong Kong. Right: PASCAL DE SARTHE and VINCENT DE SARTHE at De Sarthe, Beijing, 2016. Courtesy De Sarthe, Hong Kong.

Elaine: You have worked alongside your son Vincent—in Beijing, Hong Kong, and now in Scottsdale. How do you envision your gallery’s legacy—what do you hope will endure, and what will evolve? Are there any early lessons that still resonate as you and your son lead the gallery into this next chapter?

Pascal: Vincent and I are united by a deep passion for contemporary art. Our daily conversations revolve far more around artistic vision and creative expression than business strategies. As we navigate this period of transition—both within our gallery and the broader art world—we recognize that evolution is inevitable, even if its direction remains uncertain. One enduring principle is the importance of building relationships with young artists. Their fresh perspectives and innovative ideas will help shape and carry our vision forward. Above all, we remain committed to the integrity of art itself, never compromising our values for financial gain. Early lessons—such as staying true to artistic purpose and embracing change with an open mind—continue to guide us as we undertake this new chapter together.

Elaine: What are your criteria for a “successful” exhibition—not just in terms of sales or prestige, but in the deeper sense of what you hope audiences and collectors take away from visiting your gallery?

Pascal: For me, a successful exhibition is one that lingers in the mind long after the visit— where viewers may not fully grasp everything they’ve seen but continue to reflect on it, discuss it, and share their thoughts with others. That spark of curiosity not only draws more visitors but also fosters meaningful discourses beyond the gallery walls.

Elaine: You have witnessed significant change since you began in the late 1970s. How has visitor engagement with galleries changed? Do you see part of your task as slowing down, challenging, or otherwise changing audience habits? Do you believe there is a desire for this from audiences?

Pascal: In the late 1970s, the art market was a much smaller and more intimate environment. Without the internet, everything moved at a slower, more deliberate pace. Saturdays were dedicated to visitors, and collectors engaged in substantial and unhurried discussions with gallerists. Even then, certain contemporary art stars commanded high prices, although many of those names have since faded from memory. What has truly changed is the scale: today, the market has expanded exponentially. Galleries that merely focused on displaying conventional paintings on walls may risk losing relevance. A new generation, raised with smartphones, digital connectivity, and gaming, will demand more challenging and dynamic forms of what we now call “art.” That said, there will always be those who resist technological shifts, seeking nostalgia in tradition. For them, the brick-and-mortar gallery will retain its significance. When it comes to contemporary art, I believe we must embrace evolution. Nostalgia has its place, but it belongs to the classics of the 20th century. Today’s art should break new ground and reflect the changing world.