Market

An Architecture for Art: The Rise of Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi’s ambition to be the cultural capital of the UAE may be unparalleled, and as 2025 comes to a close, it is going full force. The Natural History Museum Abu Dhabi, designed by Dutch architects Mecanoo to resemble pearlescent cubist rock formations, opened this past weekend, featuring the Christie’s-auctioned Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton “Stan” on public display. Just opposite it is the Foster + Partners designed Zayed National Museum with its biophilic latticed sails in the form of a falcon’s flight feathers, due to open in a matter of weeks. These institutions join the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which opened in 2017, and teamLab Phenomena Abu Dhabi, a permanent interactive art museum dedicated to its eponymous artist collective, launched in the first half of 2025. Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island, its cultural hub, is showcasing only greatest hits.

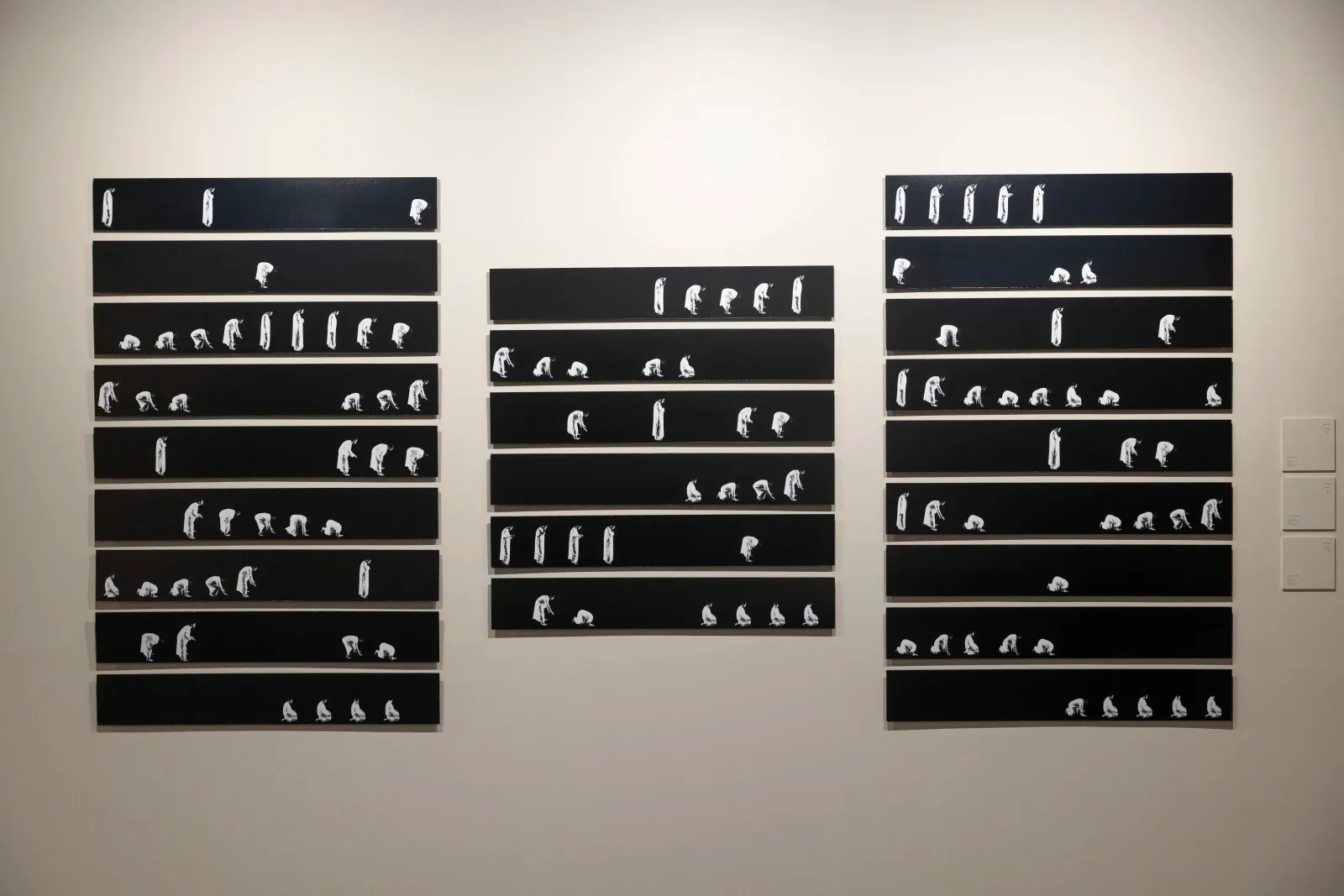

Abu Dhabi’s cultural clout is only set to increase with the expected 2026 opening of the Frank Gehry-designed Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and the Frieze rebranding of the Abu Dhabi Art fair. Early institutions, like the Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation, designed by Walter Gropius’s The Architects Collaborative and opened in 1981, housed Abu Dhabi’s first national library, exhibition gallery, and auditorium. Today, the foundation continues to host artist residencies and exhibitions, including the current shows “Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim: Two Clouds in the Night Sky,” featuring the namesake Emirati pioneering artist, and Dirwaza Curatorial Lab’s “And After,” which includes works by Emirati artist Ammar Al Attar as well as Abu Dhabi- and Singapore-based Leila Shirazi, among others. Working primarily in photography, Al Attar presented his Salah series (2015–), a triptych of monotone works showing him as he progresses through various Islamic prayer positions throughout the day.

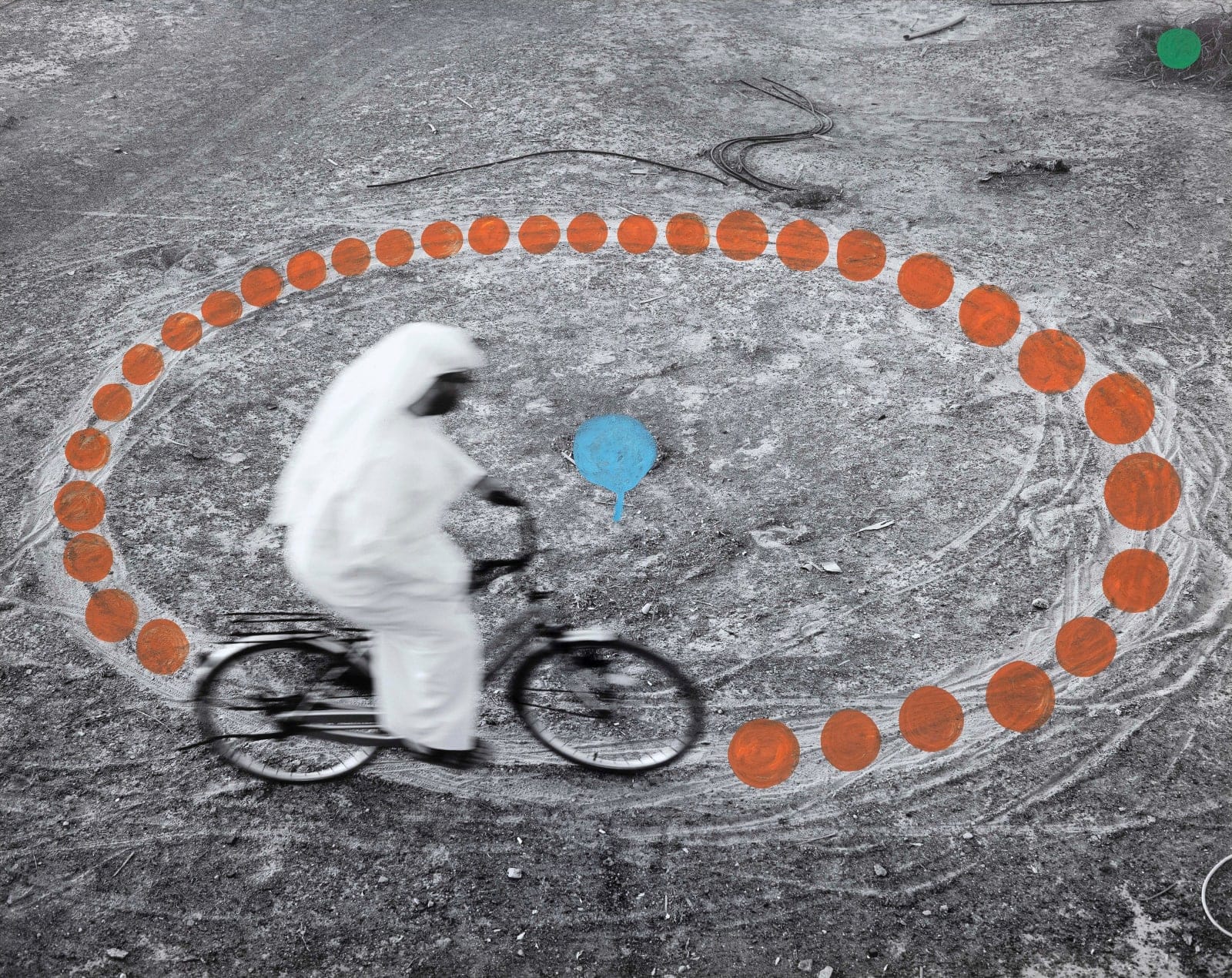

“Ammar Al Attar: Silent Residues” is currently on display at Iris Projects, a gallery situated in the rapidly gentrifying district of Mina Zayed (MiZa), which is home to numerous port warehouses. Al Attar’s latest works feature photographs depicting everyday life in the desert near Sharjah, while the artist performed mundane activities such as riding a bicycle in circles or slouched over a pile of cement bags. These images are then overlaid with painted circles and vibrant annotations, highlighting the repetitive and ritualistic in both landscape and life.

The MiZa district also hosts the independent space 421 Arts Campus, which organizes exhibitions and programs focused on artists from the Gulf and the wider region. In “Rays, Ripples, Residue,” an exhibition commemorating the organization’s 10th anniversary, three curators—Munira Al Sayegh, Nadine Khalil, and Murtaza Vali—each curated a segment of the exhibition with the passing of time as a common premise. Vali, inspired by the omnipresent sun that regulates our daily rhythm, included Dubai-born artist Lantian Xie’s Sunshine (2018). This work comprises a table-top filled with a discontinued bottled-water product in orange packaging, infused with Vitamin D and ironically marketed for the sun-drenched Gulf market. He also selected Pratchaya Phinthong’s We are lived by powers we pretend to understand (2024), where the artist transformed sandblasted granite panels into objects resembling solar panels. This piece effectively turns futuristic technology into archaeological artifact, appearing like gravestones mourning a climate crisis that even sustainable energies cannot redeem.

Independent spaces like 421 Arts Campus provide important architecture for showcasing artistic excellence. Xie, an artist featured in biennales including the 57th Venice Biennale (2017), and Pratchaya, who recently won this year’s Sharjah Biennial Prize, exemplify this. An hour and a half away, Dubai’s independent Jameel Arts Centre presented “Seas are sweet, fish tears are salty,” Saudi artist Mohammad Alfaraj’s first institutional solo exhibition. Alfaraj, recipient of the inaugural Art Basel Emerging Artist Award in May, also showed his Untitled (palm) (2025) series of charcoal-on-paper palm trees of varying heights at the Abu Dhabi Art fair with Saudi-based Athr Gallery in collaboration with Paris-based Mennour gallery, receiving a sold-out reception and commissions for new works.

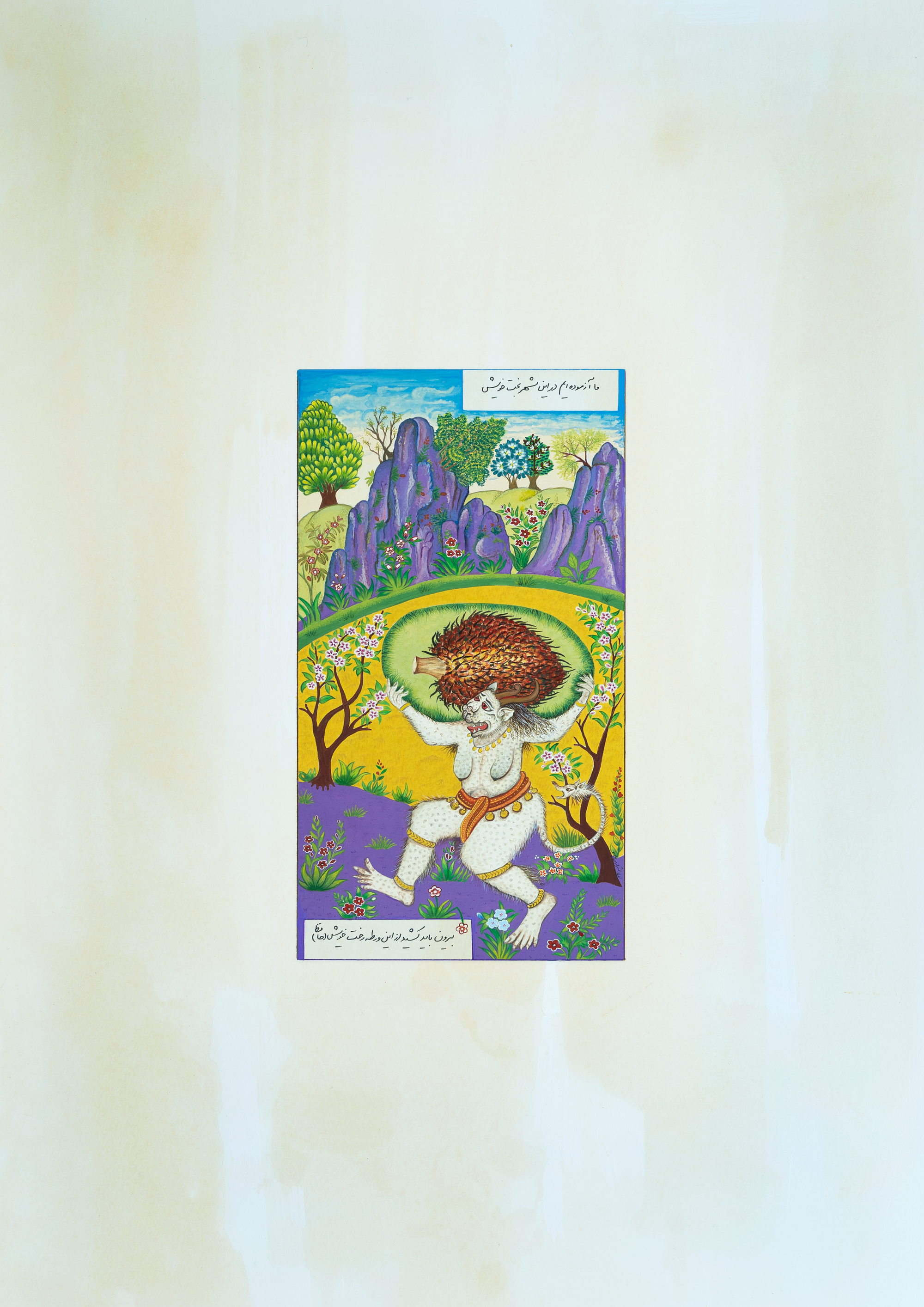

In this vein, the fair provided a framework for art that extends beyond mere transactions. Aside from the exhibition at the Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation where Shirazi was a 2024 artist residency alumnus, her work is included in Guggenheim Abu Dhabi First Nations adjunct curator Brook Andrew’s group show, “Seeds of Memory: Migration as Ceremony, Survival and Renewal,” the anchor exhibition of the Abu Dhabi Art fair. The show also included the works of Indigenous Australian artist Betty Muffler, Syrian artist Issam Kourbaj, and the Philippine diasporic collective, Sa Tahanan Co. In the exhibition, Shirazi presented a series of works that, at first glance, resemble 14th- to 17th-century Persian or Mughal “miniature” paintings. She transposed these to a contemporary context, incorporating elements of her research into the colonial history of the oil palm as a plantation crop originally from West Africa.

Shirazi’s experiences in Malaysia and her journeys northward through the Malay peninsula to Thailand exposed her to trucks carrying harvested oil palm fruits destined for processing into jet fuel, pharmaceuticals, and cooking oil. This monoculture causes significant ecological damage, as do logging trucks transporting rainforest timber south of the Thai border. In Untitled (حرکت جوهری ۲ // Substantial Motion II) (2021), Shirazi portrayed the “Div,” a horned demon-like creature in Persian mythology, set against an Edenic landscape and carrying a sack of oil palm fruits on its back. The figure appears ready to hurl the spiky mass back at humankind in retribution for its extensive environmental destruction.

The Abu Dhabi model is one where the government spearheaded artistic and cultural programming through its Department of Culture and Tourism (DCT), with the Abu Dhabi Art fair serving as one of the department’s flagship events. The DCT’s initiatives appeared to be paying off. International galleries have responded strongly over the years, with sizable contingents from places as disparate as Nigeria (kó Gallery) and Hong Kong (Hanart TZ Gallery, Rossi & Rossi) joining this latest edition, marking an overall 40-percent boost in participation at 142 galleries. First-time participant Takato Kano Gallery, which has locations in Nagoya and Yokohama, is even planning to open a permanent space in Abu Dhabi. At the fair, the gallery is showcasing works by Japanese women artists from the 19th to 21st century, with Yayoi Kusama being its youngest inclusion.

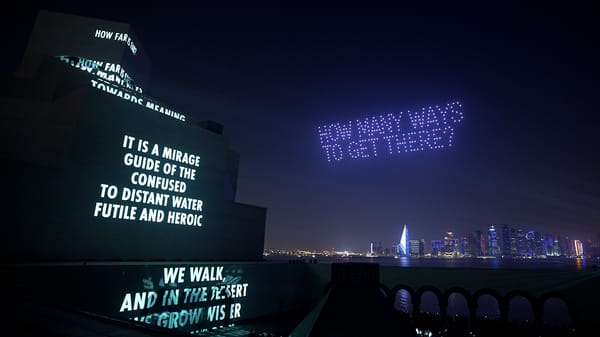

With the Abu Dhabi Art fair set to be rebranded as a Frieze Abu Dhabi in 2026, the increased buzz suggested it might outgrow its current home at Manarat Al Saadiyat, a purpose-built venue for art fairs and exhibitions on Saadiyat Island, as it goes head-to-head with Art Basel Qatar, which debuts in February 2026. Alongside the fair, the DCT concurrently spearheaded Manar Abu Dhabi—a biannual, light-based installation art initiative under its Public Art Abu Dhabi program aimed at democratizing art through integration with public architecture.

Curated by Singaporean artistic director Khai Hori, formerly senior curator at the Singapore Art Museum and deputy director of artistic programming at Palais de Tokyo, the initiative—named for the Arabic word meaning “lighthouse”—spanned four key locations with 22 newly commissioned sculptures, immersive works, and projections. The parcours format required, unusually, a two-hour, 140-kilometer-per-hour car ride to the neighboring city of Al Ain, inviting audiences to engage with its leafy oases and surrounding desert landscapes.

Perhaps the most breathtaking artwork was that of Dubai- and Abu Dhabi-based Shaikha Al Mazrou, whose piece on Jubail Island, The Contingent Object (2025), was accessible only by a 10-minute buggy ride through gazelle habitat and across a sandy peninsula framed by saltwater mangroves and estuaries at nightfall. Al Mazrou’s work glowed softly in the darkness—a large illuminated pool, 30 meters in diameter. Its bund and base were constructed entirely from salt sourced from the local salt industry and filled with pink water. The color resulted from crystallization and pigments from algae growth, presenting as concentrated hues that accumulated around the curvilinear ridges on the pool’s base. The work is a masterclass in land- and bio-art by the Emirati woman artist and sculptor, who is 37 years old—and the antithesis to all that was loud and flashy on that terra firma.

Manar Abu Dhabi also served as a test bed for public art that might become permanent fixtures in the city, with Studio DRIFT’s Whispers (2025) being a strong contender. The work, a crowd favorite, features a meadow in the sand filled with hundreds of two-meter-tall spikes that attenuate and split into branched forms resembling grass seeds that are illuminated by optical fibers. Visitors meandered around these seed stalks, which bent in the wind and lost luminosity as they tilted, reigniting when they bounced back to an upright position. Should Whispers become permanent, its fragile stalks would have to be reinforced to protect them from a boisterous public, especially where no docents are present.

In any case, the idea of permanence was a contested one. Up until the 2010s, the modernist Abu Dhabi Cultural Foundation was reportedly slated for demolition after renovations, which had commenced in 2009 but stalled. Abu Dhabi would have lost an icon that predated its starchitect museums on Saadiyat Island and that stood for the importance of culture and the arts for most of Abu Dhabi’s short history since independence. While it is tempting to gravitate toward the shiny and new, these developments may also contain ancient dinosaur bones of the past—the kind visitors come from all over the world to see. This is the draw of Abu Dhabi and its multitude of cultural and artistic offerings, all supported by an architecture for art.

Ryan Su is a Singapore-based contributing editor for ArtAsiaPacific, focusing on art and law. He is a practicing lawyer, and an accredited mediator and arbitrator.