Issue

One on One: Greg Girard on Paul Bowles

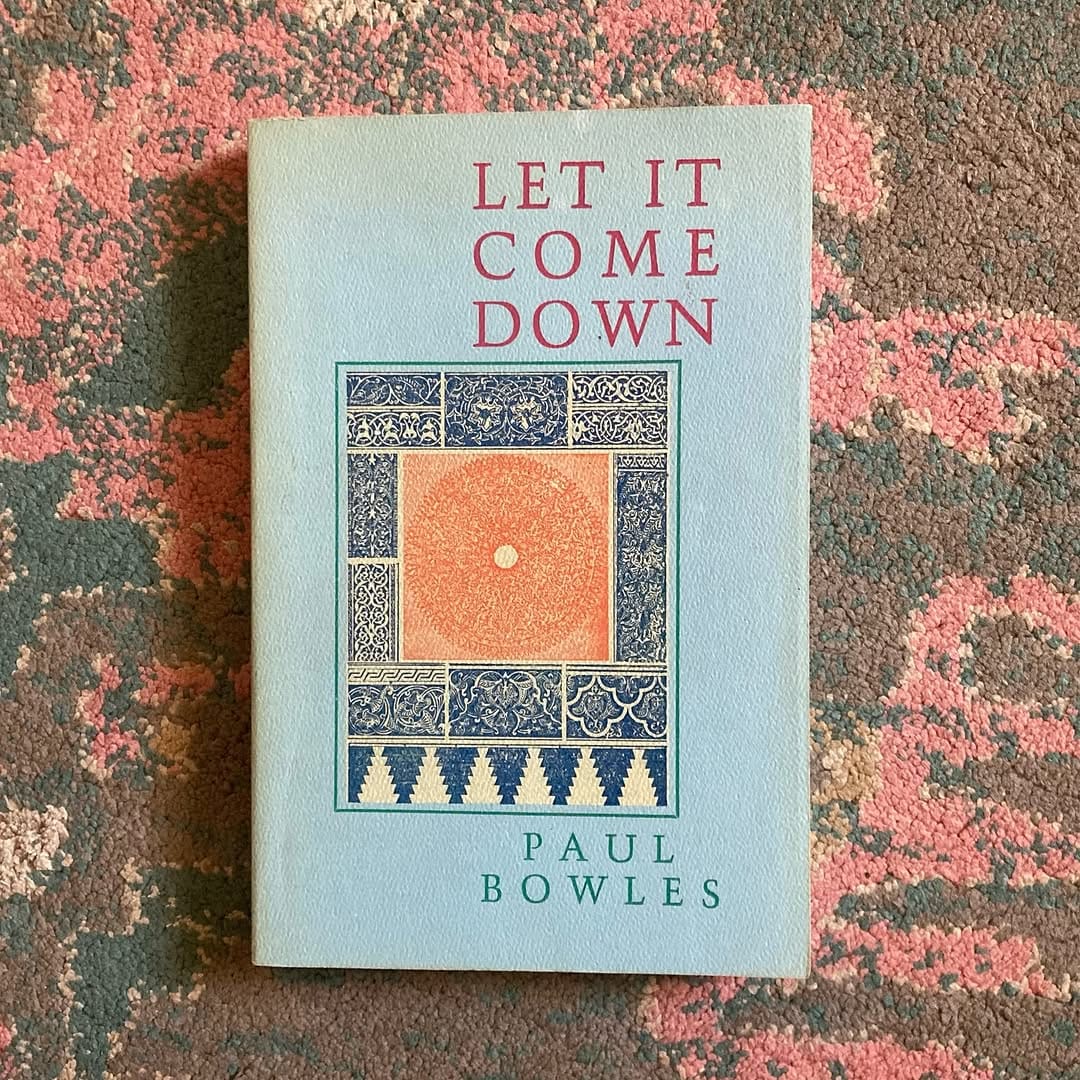

I first encountered the work of Paul Bowles via his 1952 novel Let It Come Down while I was browsing in a book shop. I picked it off the shelf, opened it, and read the reference from MacBeth inside.

Banquo: It will be rain to-night.

1st Murderer: Let it come down.

(They set upon Banquo.)

Those stark, pitiless four words were a good indication of what was to follow. Bowles’s writing has a dated quality, like watching a black-and-white movie from the 1950s that you’d never heard of but were immediately transported by nonetheless. By the spare prose with its atmosphere of distance and vague alienation. A stranger arriving at and disappearing into a foreign place (in this case an American in Tangier’s International Zone, sent by his company). That lack of personal volition, being dispatched rather than deciding by one’s self, is perhaps a key foil. Having to be there rather than wanting to be there, duty rather than curiosity, at least in the beginning. In the postwar world that was how and why so many Americans populated foreign places: sent to manage, build, and exploit foreign opportunities.

The term “exotic” has acquired a rather tainted meaning of late. Projected fantasies, attraction without understanding, the ignorance and entitlement of the West in the non-West. In Bowles’s version of the exotic, however, it is the ignorant Westerner that has no idea what’s in store, thinking mistakenly that his Westernness will protect him. Not realizing that it won’t until it’s too late.

I was moved by Bowles’s novel, and started reading everything I could find by him. His books, first published in the 1950s and out of print for many years, were then newly republished by Black Sparrow Press, with their distinctive, photo-less cover designs and uncoated paper stock. They look more like limited editions of poetry than novels. The publisher was located in Santa Barbara, California, and I wanted to tell Bowles how much his books meant to me. An opportunity presented itself when I lent my copy of Let it Come Down to a friend. Soon after, she reported back that her car had been broken into but, among the books on the front seat, nothing had been stolen besides the Bowles novel. I wrote to Bowles about this, care of his publisher, and asked a question or two hoping to elicit a reply. Two weeks later, an air mail envelope in robin’s egg blue arrived with Moroccan stamps and a Tangier return address. His letter began: