Ideas

The Chess Players’ Lore

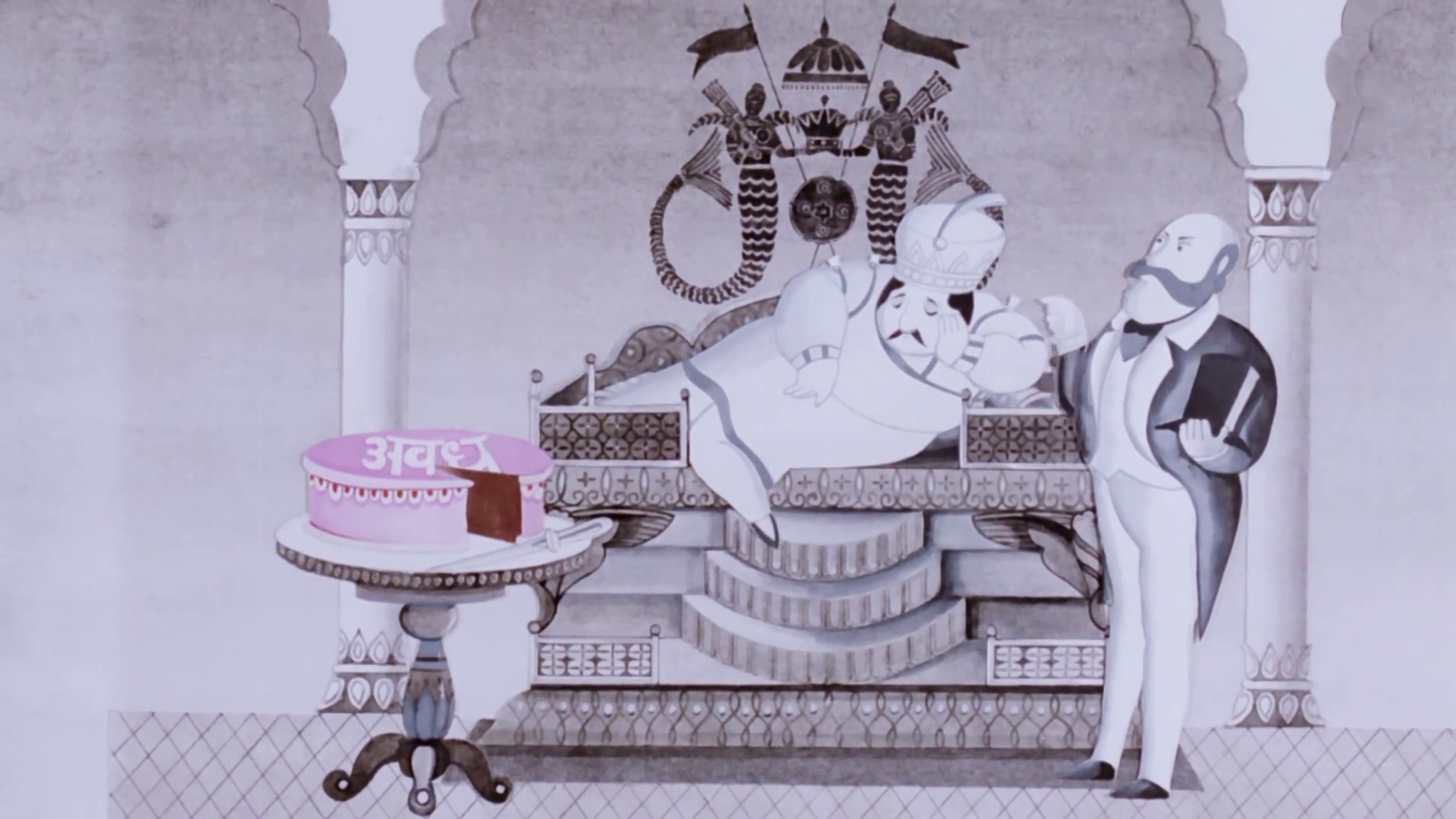

Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players) (1977) is a film that gives solace to the mind in restless times. Directed by Satyajit Ray, the late cinema titan known for his poetic realism, the film depicts the East India Company’s annexation of the kingdom of Awadh. Despite the imminent invasion of the capital city of Lucknow, two landed gentries are so engrossed in chess that they neglect their households, let alone affairs of the state.

The subplot is based on a story written by Premchand, a cautionary tale on feudal decadence. Yet, Ray’s version is more whimsical: Mirza and Mir are nepotism babies who squander their days playing chess, lifting their arms only to move the pieces or smoke hookahs. One day, a friend taught them the rules of English chess, which involves a formidable queen and a faster pace. Laughing it off, they care for neither the modernized gameplay nor the railways newly built by the British. In fact, they dodge political discourse as desperately as they dodge their wives.

Feinting a headache, Mirza’s wife Khurshid draws her spouse from the chessboard to the bedchamber. He is so preoccupied with chess that he fails to warm up his full attention. “You will know tomorrow how much I love you. Agreed?” The camera pans to a thwarted Khurshid as the man returns to his game. (Typical!) Conversely, Mir’s wife Nafisa has already given up and is having an affair. In a comical act, she claims that her lover is hiding under the bed from a draft prior to the invasion. Her husband is so spooked by potential military action that he’s fooled.

In love, Nafisa makes realpolitik moves, while Khurshid’s sentimentality brings her tears. I wonder who has the better marriage.

In real history, the East India Company hatched another game. Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the King of Awadh, had maintained a friendship with the Company until 1856. His reign was protected by their army as long as he paid the cost and issued loans whenever they demanded. An absent yet beloved ruler, he was a lavish patron of the arts and had himself composed singsong proses. His wanton rule vexed the British. A report from the Residency claims “the Garden of India was fast becoming a thorn-covered wilderness . . . The king amused himself with a court of fiddlers, singers, buffoons, and dancing-girls.” Around the time, General James Outram was appointed resident at Lucknow. His mission was to depose the king with the pretext of misrule and to annex Awadh without any bloodshed—an ostensibly illegal move according to the last treaty signed between the King and the Company.

The film shows the clash between the colonial and the Indigenous with Shakespearean monologues. General Outram (Richard Attenborough) is perplexed by a ruler who is effeminate and irresponsible in his eyes. With a clockwork conception of time, he is hesitant but sees his duty as inevitable progress: “I don’t like it . . . Yet, we have to go through it.” Contrarily, the king (Amjad Khan) is at ease with his identity and power: “They loved me . . . They knew what kind of a king I was . . . How many of Queen Victoria’s subjects sing their songs?” As noted by some critics, his Indian androgyny resembles that of Krishna, the deity represented both as a warrior and a lover.

In statecraft, the British exercises ruthless logic, while the king plays like he’s flying his kite. Historically, he was exiled from his country in 1856. Still believing in justice, his family went to London to plead to Queen Victoria. Yet, the political rules changed after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, which began the Crown Rule of India. Lucknow was forever lost to the Nawab.

Like the nuanced history of colonial India, Satyajit Ray’s tale defies easy interpretation. Each character simultaneously displays an understanding of the game and puzzlement toward their opponents’ moves. While some condemn the royals in the film as undutiful lotus-eaters, theorist Reena Dub marks their native courtesy, one that is evident in another Lucknawi tall tale—when a British train arrives, two nobles are so busy waving “after you” that they miss the punctual train—a self-mockery that leads to proud reflection rather than shame. Made during a time of emergency and censorship, Shatranj Ke Khilari gives respite to momentary bliss and ambient unease.

Shatranj Ke Khilari is on view on Youtube. It will be screened on October 15, 2022 at Asia Society, Houston for the 14th Indian Film Festival of Houston.

Curated by an ArtAsiaPacific editor, “Lore” is a biweekly blog that probes into the histories and mythologies of media.