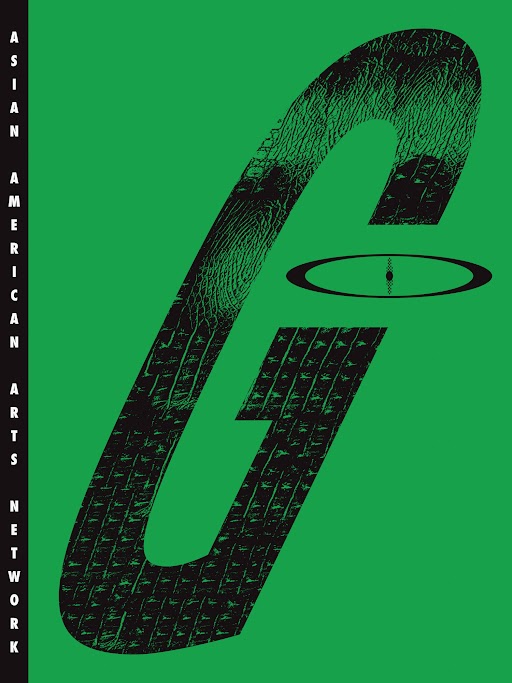

Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001

By Alex Jen

Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990-2001 edited by Howie Chen, published by Primary Information, New York, 2021. Photography by Peter Chung for ArtAsiaPacific.

Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001

Edited by Howie Chen

Published by Primary Information, New York, 2021

Often pictured with a single, unblinking eye as its logo, Godzilla began with three friends in a Brooklyn studio in 1990 and expanded within five years to an amorphous collective of Asian American artists, curators, and writers numbering 2,000 across the United States. The group’s goal was to build an Asian American art history through community conversation, critique, and exhibitions. Its rapid growth and success lay in its avoidance of hierarchy and overdetermination—membership was open, and new definitions of Asian American identity were regularly accepted and debated. As a Xeroxed, handwritten note from a 1994 grant submitted by Godzilla reads: “Isolated with few resources. We want to contribute to changing the limited ways Asian Pacific Americans participate in and are represented in our society.” Fittingly, these lines double as the epigraph of the anthology detailing the collective’s activities from 1990 to 2001.

Group portrait of the members of Godzilla: Asian

American Arts Network, taken in 1991 for the cover of Godzilla Newsletter 1,

no. 1 (Spring 1991). Back row (L

Paging through the volume is like digging through boxes in an archive, not knowing what you’re going to find. The book design, by Ella, is unobtrusive but encouraging. In lieu of a table of contents, there are yearly intertitles; readers can flip in order or dig into the collective’s history at any juncture. Those looking to orient themselves can start with editor Howie Chen’s introductory essay, or with early member Karin Higa’s incisive essay “Origin Myths: A Short and Incomplete History of Godzilla,” before delving into the rest of the 500-plus pages, which are packed with scans of meeting minutes, press releases, letters, full reproductions of pamphlets and journal articles, and exhibition photos.

There is something endearing about seeing art reproductions from before smartphones—most of the anthology’s materials were printed and saved for years before being shared with us, replete with scanner blurs and too-dark images. Members cycle in and out of the book, which becomes a meaningful social record of generations passing the baton. Early on in 1991, David Medalla visits the group for a potluck at the Chinatown History Museum (“Godzilla eats,” the announcement teases in the third person). That same year, Godzilla penned a respectful yet stern letter to director David Ross of the Whitney Museum of American Art, which has now made history, drawing his attention to the “conspicuous absence of Asian American visual artists in the [1991] Biennial.” And in 1993, Godzilla revealed its irreverent, personal side with an installation of trinket-like artworks titled The Curio Shop at Artists Space.

Toward the millennium, as Higa details, Godzilla petered out as “‘Asian American art’ came to signify a specific type of artistic practice rather than a set of artistic interrogations.” Nevertheless, in 2021, Godzilla withdrew from an exhibition curated in its honor at the Museum of Chinese in America, protesting the concessions that the institution had received for the construction of a new Chinatown jail—many of the original members signed the letter, reaffirming the lasting values Godzilla has left on the art world, even after its dissipation.